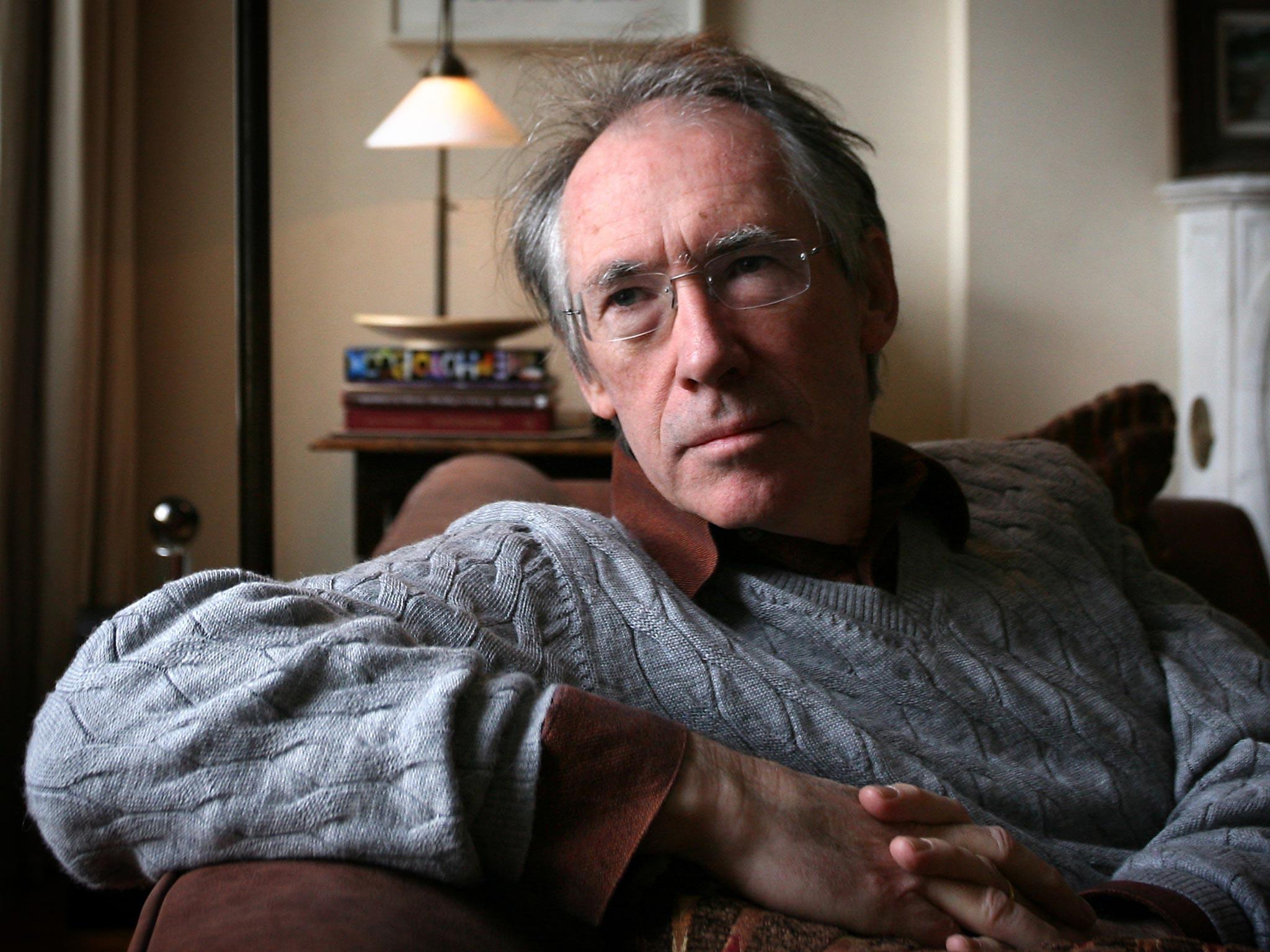

Ian McEwan, The Children Act, book review: A thrillingly grown up read

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.British culture has lately taken not so much a child-like but a puerile turn in its reflex demonisation of all figures of authority. High-profile cases of corruption and malpractice have not only aroused righteous anger. They have licensed a petulant, even infantile, refusal to engage with the exercise of power for good as well as ill.

In much of his fiction, above all in Atonement, Ian McEwan has shown how the precocious misdeeds of the wayward young can co-exist with a kind of innocence. More recent books have imagined high-status figures in ripe middle age who can be foolish, roguish or just acutely vulnerable, in spite of all their eminence and influence.

From the crisis-stricken neurosurgeon Henry Perowne in Saturday to the Nobel Prize-winning physicist and all-round scallywag Michael Beard in Solar, McEwan has given us the great and good in trouble, in doubt, in a mess. Not only can he inhabit the burdens of responsibility but - from as far back as Charles Darke, the politician who regresses to boyhood in The Child in Time (1987) - he can imagine the urge to throw it all away.

Fiona Maye, his latest shaken pillar of the Establishment, is a good woman and a wise judge. Within the Family Division of the High Court in London, she presides – a female, childless, 59-year-old Solomon – over a realm of “strange differences, special pleading, intimate half-truths, exotic accusation”. As parents and spouses appeal to her from the bitter depths of “vicious combat with the one they once loved”, she struggles to temper justice with reason, compassion and eloquence. The most inextricable emotional knots of divorce, custody and consent land in her nimble and sensitive hands. Noted for their “crisp prose, almost ironic, almost warm” (a bit like her creator’s?), Mrs Justice Maye’s verdicts aspire to the “unassailable definition” of the classic judgment. We see her not merely as a caring law-giver but, in her own fashion, an artist as well.

Needless to say, her little paradise of reason and enlightenment harbours a serpent or two. At home in their Gray’s Inn apartment, academic husband Jack mourns the death of their once-sultry sex life. He wants to embark (with a young statistician) on a “big, passionate affair”. Stereotypical late-career folly it may be, but Jack’s adventure confirms to Fiona that “for all a lifetime’s entanglement in human weakness, she remained an innocent”. When he storms off into yet another rainy night during the sodden midsummer of 2012, this paragon of cool intellect gets the locks changed. Betrayed, even Fiona can dive “down there with the rest, swimming with the desolate tide”.

This temporary absence is soon righted when Jack slinks back from his paltry fling and, by slow degrees, the couple thaw out their marriage. But behind it lies the greater emptiness of her never-born children, despite the “small village” of niece-and-nephew photos clustered on her piano. Fiona feels her childlessness as “a flight from her proper destiny”. It is her sacrifice, her wound, even if - for a woman of her period and profession - a fairly common one.

The judgments that make her name can still haunt her sleep: such as her decision to save one conjoined infant twin by depriving its parasitic sibling of life. As with several of Fiona’s ethical dilemmas, McEwan draws (as he notes in an afterword) details from actual cases – here, the “Jodie and Mary” hearings of 2000. She also has an acute sense of the deep harm done when justice fails. Fiona can’t forget that a wisecracking colleague credited dud statistics and so condemned a guiltless mother who had seen two babies die from “sudden infant death syndrome” (the tragic fate of solicitor Sally Clark). For her, “the law was at its worst not an ass but a snake, a poisonous snake”.

Then the judge’s own time of trial begins in earnest. Adam, a bright, charming boy three months shy of his 18 birthday, lies at death’s door in a south London hospital. A Jehovah’s Witness, like his devout parents, he rejects – as do they – the blood transfusion that would allow combined drugs to treat his leukaemia. Again, McEwan picks this moral maze from court records (although the boy in the principal case he cites was just under 16) but tracks it humanely through Fiona’s supple, subtle mind and easily-pricked conscience. As the Children Act of 1989 demands, she must rule in the interests of Adam’s welfare. But should a teenager - still a minor, and raised within the “uninterrupted monochrome” of a closed religious system - choose to risk and probably end his own life? Fiona decides to permit the transfusion and so define “welfare” against the will of the patient, his parents and his creed – but not before an unorthodox visit to Adam’s hospital bedside, where she and the “lovely boy” bond.

Fiona at first believes that she has deprogrammed, or maybe “deradicalised”, Adam. Rescued from his sickness, he seems to spurn the Witnesses and embrace her world of doctrine-free autonomy and rationality, “open and beautiful and terrifying”. Adam even tells her that his faith has “collapsed into the truth”. McEwan the public figure, who argues so cogently for science and reason against supernatural dogmatism, might leave a feelgood fable of secular enlightenment at that. McEwan the novelist, of course, has a far stranger story to tell. Forged in music, poetry and talk, the friendship of these two super-intelligent “innocents” – the omniscient nearly-60 judge and the ailing, headstrong adolescent – will lead not into light but darkness.

As compact, focused and elegant as one of Fiona’s own judgments, The Children Act sticks by and large to her perspective. Adam, whose antic neediness harks back to the obsession theme of Enduring Love, is a touching but sporadic presence. The book moves to the rhythms of her mind. A talented amateur pianist, Fiona can wow the Gray’s Inn benchers with her renderings of Schubert. But (much to Jack’s chagrin) she can’t play jazz: “No pulse, no instinct for syncopation, no freedom… Respect for the rules”. In befriending Adam, she tries her hand with a little – legal and moral – jazz. It cannot end well.

The Children Act shares the virtues of its heroine – and, you might argue, some of her strict-tempo limitations too. Fiona, the purest recruit to McEwan’s line of wounded healers and flawed arbiters, makes us feel the frequent agony and fleeting ecstasy of institutional authority. Although thrillingly close to the child within us, McEwan nonetheless writes for, and about, the grown-ups. In a climate that breeds juvenile cynicism, we more than ever need his adult art.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments