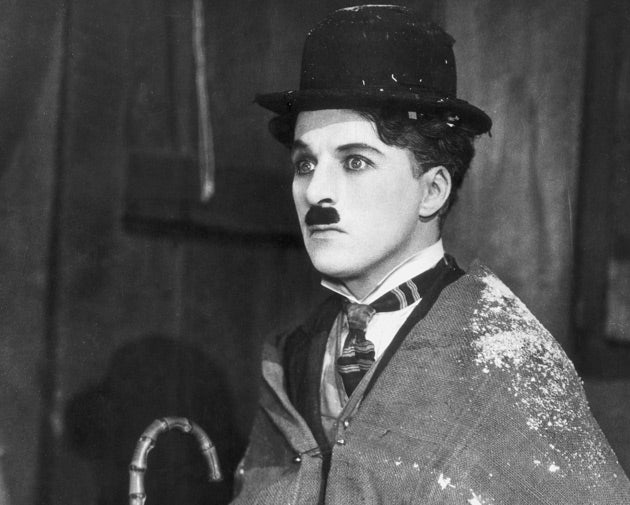

Chaplin: The Tramp's Odyssey, By Simon Louvish

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."Why another book?" asks Simon Louvish, at the beginning of this dense tome. It's more than 30 years since Charles Chaplin died, there's no anniversary in the offing, and there are lots of books about him, as the bibliography at the back of this one confirms. Louvish's sources are mainly secondary and he makes no boasts about new revelations. Yet it's a mark of his rich scholarship (and the richness of his subject) that you finish this book feeling glad he wrote it, rather than wondering why he did.

Louvish has written biographies of WC Fields, Mae West and Cecil B DeMille (as well as Laurel & Hardy and the Marx Brothers), but this book isn't really a rounded portrait. It's more of a cinematic critique. That's not to say it's dull: Chaplin's life story was so colourful, it would be hard to write a boring book about him.

But you end up little wiser about the man himself. Although Louvish charts the main landmarks of the life, his fascination is for the movies. He's not that bothered about the man behind the mask; more interested in the mask itself – The Tramp, not Charlie Chaplin.

Chaplin's Tramp persona made him the most famous man on earth. Gandhi was the only man he met who had never seen his films. However Louvish shows this alter ego was a familiar music-hall archetype, one of many that Chaplin toyed with at the start of his career. Its genius was its simplicity. It was a blank canvas, onto which every viewer could project almost anything they wanted.

Iconic and ubiquitous, Chaplin was the first global superstar, yet despite all the publicity (or maybe, in a way, because of it) his personality remains a puzzle. Why did he tell such porkies about his early life? Why was he so attracted to (very) young women? Louvish records these controversies but never gets to the bottom of them. The picture that emerges is of a strangely disconnected figure – an immensely powerful and wealthy man who only really felt at ease playing a down-and-out.

"I am no one," Chaplin told a journalist, soon after he landed in America. "There is absolutely nothing interesting about me." He was wrong about the second point but right about the first. Although his life reads like a lurid melodrama, anonymity was the key to his appeal.

Louvish makes light work of Chaplin's rags-to-riches CV – the maddened mother, the alcoholic father, the workhouse, the emigration to America, the exile – but when he focuses solely on the films his book begins to sag. Quoting Chaplin on the comic's craft proves the point that comedians are never more humourless than when they're talking about comedy.

Louvish's prose style is sometimes similarly dry. Describing the plots of silent movies in great detail is a bad idea - they're pretty incomprehensible on the page, and rarely raise a smile. Ironically, it's when Louvish wanders off the point that his book comes alive. He's at his best philosophising about Chaplin, placing him in a broader context, citing references - Dickens, Grimaldi, Walt Whitman, Jack London, Mark Twain. You get a sense that he's more of a historian than a biographer, better at the bigger picture than intimate details – a bit like Chaplin.

Which brings us to the biggest riddle: what made Chaplin special, and is he still significant? Compared to his contemporaries, his work hasn't aged so well. Laurel & Hardy and the Marx Brothers made better transitions to the talkies. Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton both feel fresher (and funnier) today. Yet there's something elemental about him that the others lack, something a child can understand.

Though his movies seem like ancient history, his poignant influence endures. Rowan Atkinson's Mr Bean enjoys worldwide appeal, like Chaplin in his heyday. In Sacha Baron Cohen's Borat, you can see a trace of Chaplin's Tramp, the hopeless, hopeful immigrant, trying to make his way in a new world. For half a lifetime, Chaplin's pathos has been out of fashion - but if today's hard times continue, his sentimental comedy may soon be back in vogue.

William Cook's books include 'Morecambe & Wise Untold' (HarperCollins)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments