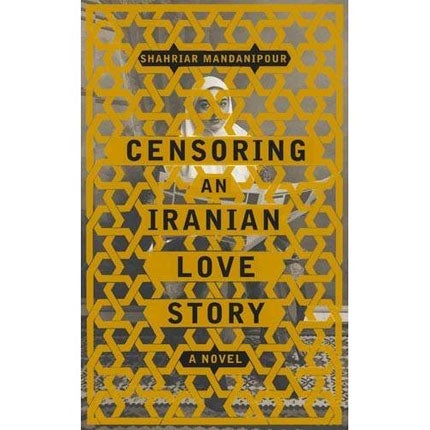

Censoring an Iranian Love Story, By Shahriar Mandanipour

Shahriar's lore loses its romance

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In Abbas Kiarostami's recent film Shirin, sonorous voices intone the classical story of the heroine and her two loves, Khusrau and Farhad.

This novel by the exiled Iranian writer Shahriar Mandanipour (translated by Sara Khalili) also quotes from Nizami's verse romance about Shirin. But Mandanipour's goal is analytical and didactic rather than subliminal and evocative. Using the story of Shirin as an example of how rich the Persian classical tradition is, he also, like many writers, selects a pre-Islamic tale to prove eroticism and passion are common in Farsi writings. These pre-Islamic tales were used by Sufi poets, from Jami to Rumi, to express their metaphysics of spiritual longing.

This story is juxtaposed with, and soon subsumed by, a love story the Kundera-esque narrator wants to write. Sara and Dara, two characters from a children's textbook, grown up and both virgins, try to live out their romance within the restrictions of their society. But the narrator has to deal with the range of prohibitions that restrict a writer in Iran. Much of this book is a record of his deletions and emotions.

The story of Dara and Sara refuses to evolve. Instead, there are ruminations on art and censorship, traditional and modern literature, the problems of loving and living in Tehran. Mandanipour's approach reminds us of the potential for both satire and innovation that postmodernism gave writers in repressive regimes, from Kundera's multiple narratives to the surrealist subversions of traditional storytelling by writers in General Zia's Pakistan.

The playful conceit of writing about Sara and Dara becomes tedious, and Mandanipour also relinquishes the Shirin story. Much of the novel becomes an essayistic exercise in metafiction. The reader might be reminded of Kundera's theory of the novel as a space where dream and reality, essay and autobi- ography, come together. But a writer must ensure that, in fiction, practice precedes theory. Mandanipour's novel, for all its dogged literariness, never makes that transition.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments