Can't we talk about something more pleasant? by Roz Chast, book review

A new direction for the graphic novel with a reflection on the sad, inevitable end

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In some families, the generation gap can yawn more like an unbridgeable generation canyon. The struggle of children to re-connect with their parents, especially in later life, has become a recurring theme in autobiographical graphic novels, from Art Spiegelman's foundational Maus to Alison Bechdel's Fun Home and Are You My Mother? Several of these, notably Joyce Farmer's Special Exits and Brian Fies' Mom's Cancer, provide one more-or-less cathartic outlet for offspring to make some order, if not sense, out of the passing of their parents.

These memoirs have recently emerged into a whole genre of graphic novels with an academic interest in medical humanities, known as Graphic Medicine. Having coined this term and set up the first annual conference on the subject in London in 2010, Welsh-born practitioner-turned-cartoonist Ian Williams will launch his own graphic novel, The Bad Doctor (reviewed in the illness 'round-up' on page 27) during the fifth conference on 26-28 June, in Baltimore.

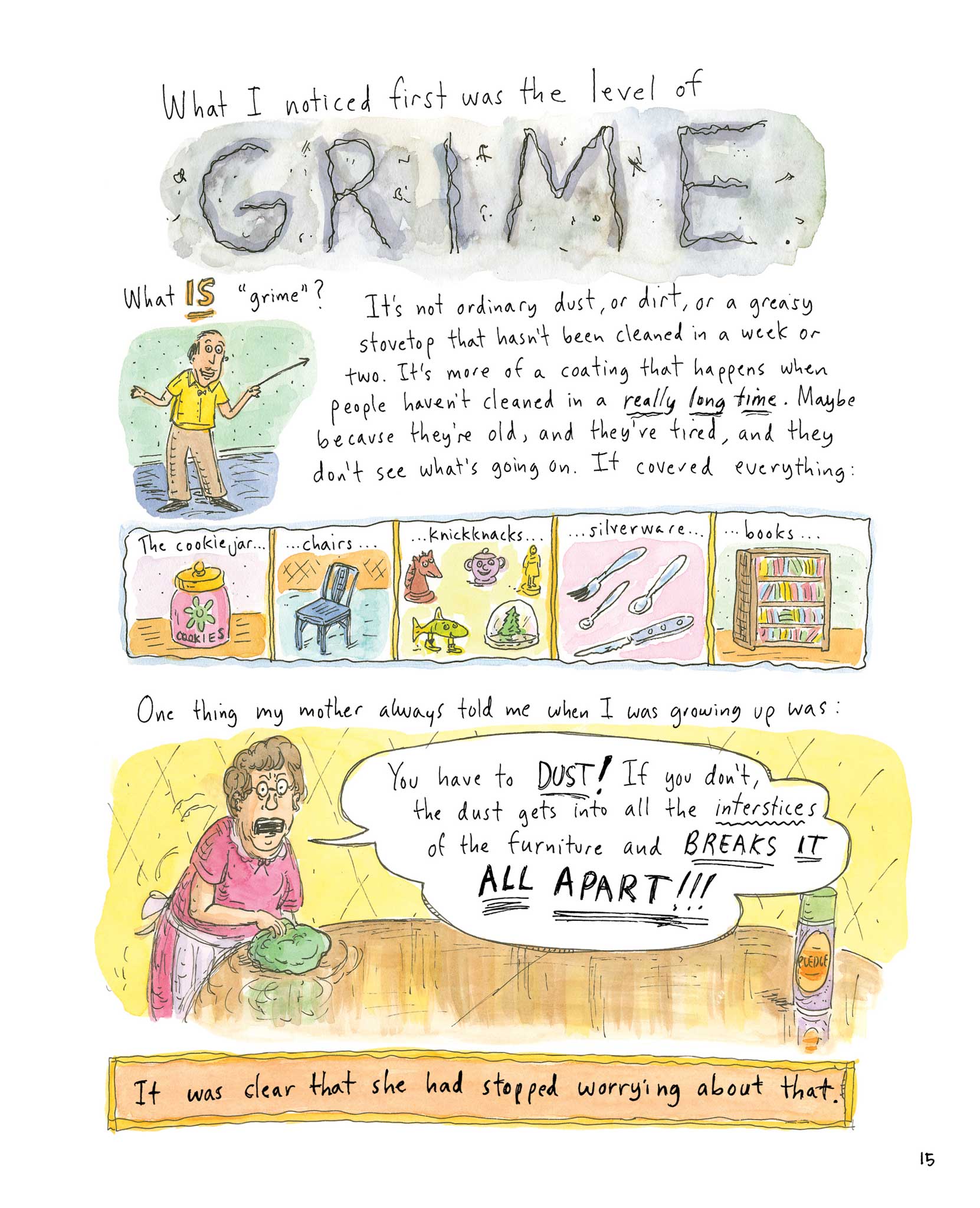

To this flourishing field, the New Yorker cartoonist Roz Chast brings an empathy-generating addition in Can't we talk about something more pleasant? Chast looks back with ambivalent humour and hindsight to 1990 and to the final years of her parents, who died in their nineties, her father George first in 2007, her mother Elizabeth in 2009. Born in 1912 only 10 days apart, raised two blocks apart in East Harlem, New York, these Jewish kids seemed predestined to be lifelong, yin-yang "soul mates".

As the forceful, take-charge Elizabeth explains, "The rocks in his head match the holes in mine!" – to which the mild, impractical George replies, "Ditto!" Probably any book about your parents can't help also being about yourself, and Chast, an only child of older parents, is candid about her contrasting relationships. Her father "liked me as a person, not just because I was his daughter", whereas she never forgot her mother informing her as a girl: "I'm not your friend. I'm your mother."

This unknowing distance comes through in the last of several black-and-white family photographs included here, which shows young Roz clearly reaching out for affection, standing with both arms around the shoulders of her mother, who sits and smiles almost regally, not reciprocating.

In something of a mixed-media project, Chast presents other photographs alongside her comics, for example shooting new snaps as mementos of some of her parents' junk before she throws it away, one showing a drawer crammed with jam lids, another a "museum of old Schick shavers". She also reproduces a couple of her mother's hand-written or typed poems. Chast's own writing and drawing gently pulses with the human hand and heart behind it, all made with the same pen and with no evidence of rulers or computers, her lettering and pictures deceptively wobbly, direct and vital.

As much a mistress of the single-panel cartoon as the comic strip, in one gag she devises a perfect symbol of her parents' gradual decline by portraying them relaxed on their two-seater sofa, mounted on a pair of skis and careening serenely down a snowy slope.

A feisty, outspoken, highly intelligent woman, Elizabeth Chast insisted she would not dwindle into "a pile of pulsating protoplasm". But illness and dementia did eventually still her and take her, aged 97. Most poignant are Chast's final, closely observed portraits in black lines of her mother's expressions, sleeping and dying. The act of drawing becomes a moving attempt to record her and keep her alive.

Chast can also be immensely practical, offering rules for cleaning out your parents' house and tips for storing their "cremains", though there's scant advice for affording America's healthcare costs.

Most of all, this book might well help the many who will face these same challenges to bridge that gap and talk about the unpleasant, yet the inevitable, as we try to do what's right and prepare for our final portrait.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments