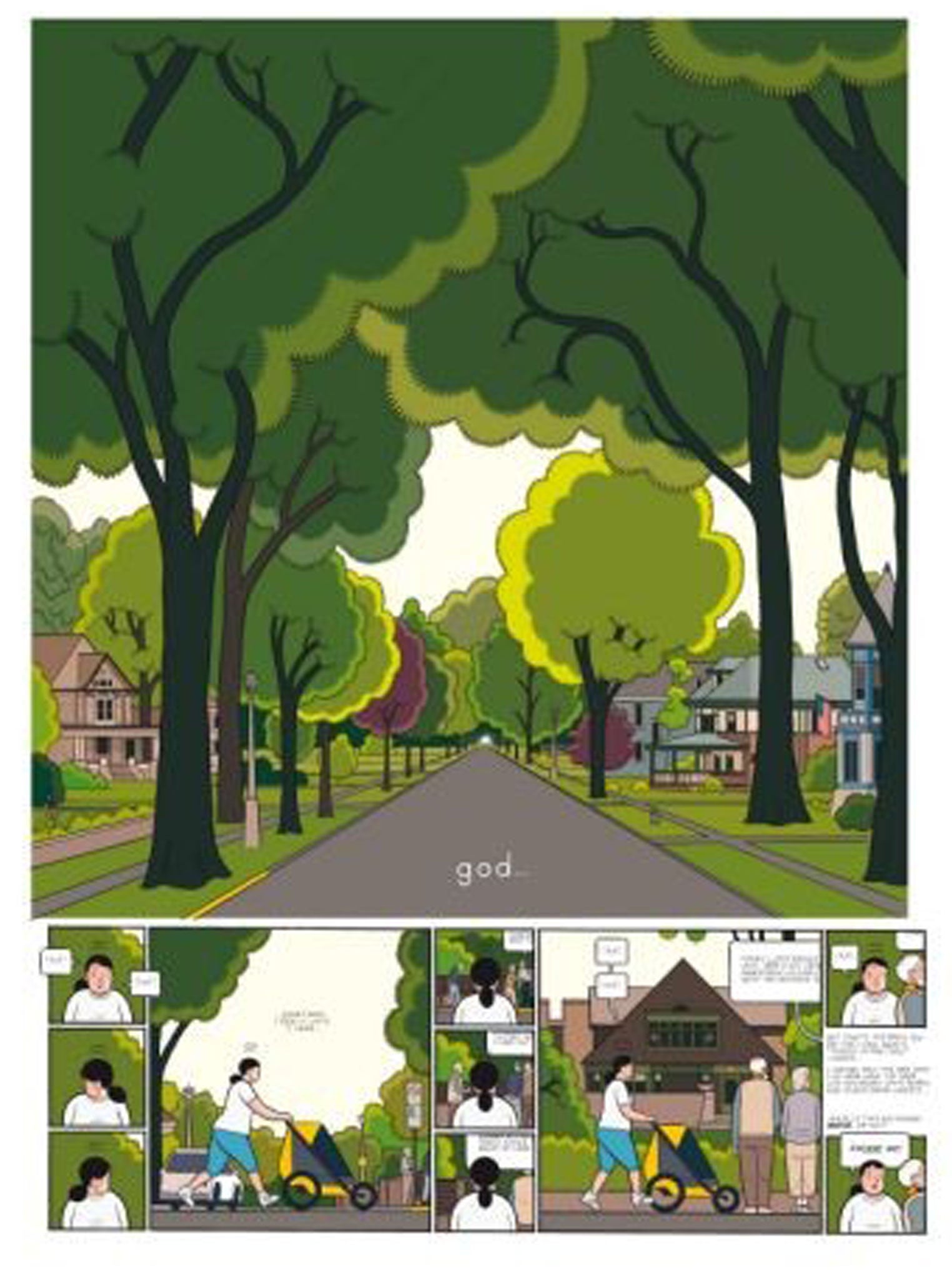

Building Stories, By Chris Ware

Behind this hugely ambitious exercise in graphic fiction lies a simple tale of loss and loneliness.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When is a book more like a game? When it's a graphic novel that comes inside a boardgame-sized box and in 14 different parts, from one-tiered, concertina-folded strips to giant broadsheet supplements.

Instead of trying to squeeze a decade's worth of his story's serialised formats into a single unified tome, as he did with his Jimmy Corrigan (2000), Chris Ware atomises Building Stories into a multi-faceted print object, to fashion "something to hold onto" in our digital, virtual age.

Get money off this book online at the Independent Bookshop

The puzzles start on the box's lid with the title's rebuses: the "B" stands next to a bee; the "IL" becomes Chicago's state of Illinois; the "ding" a doorbell chime, all clues for what awaits within. So is the base of the box, which offers a cutaway drawing of the apartment building, the setting and occasional narrator of these stories mainly about its elderly landlady and her tenants: a couple whose childless marriage is crumbling and a single woman, who emerges as Ware's principal focus.

Ware introduces this woman on the lid, sleeping in an appropriate foetal position. With the lid removed, three vignettes gracing the outside edges of the inner box reveal her partner, child, florist's job, left prosthetic lower leg and worried world-view. Without a jigsaw puzzle's finished picture to guide you, in what order do you begin piecing this together? One system could be by increasing scale, as the stash of "paper technology" arrives shrink-wrapped, piled up from biggest to smallest. Topmost is a wordless booklet of our sleeping heroine's fragmented dreams of raising her daughter.

The third page already demonstrates a heightened sensitivity in Ware's drawing, when he shows two subtly nuanced close-ups of her face, asleep and then startled awake, not at home but in a maternity ward. Though still with dots for eyes like Little Orphan Annie or Tintin, these uncommon portraits are in marked contrast to Ware's preference for small, simplified heads, often from behind, as if to leave their features and feelings to our imaginations.

These occasional portraits mark a change in Building Stories by allowing us to engage with Ware's characters at emotionally charged points in greater detail and realism, lessening their iconic remoteness. Oddly, for a cartoonist whose stated goal is to make readers feel, Ware rarely spotlights expressions on faces, as if all the actors in a play or film spent most of their time facing away from the audience.

His wariness of overt emoting and caricatural exaggeration comes through in the page "That Girl", showing a girl's flushed face at her "blubbery" departure from her boyfriend at the airport, which makes our female narrator "deeply envious."

Ware also goes to great pains to leave this main protagonist unnamed. When a former schoolmate seeks her attention over a reunion dinner, he simply calls her "Girl". This unnaming reinforces her disconnection. During her creative writing class, she listens to another female student complain about someone's assignment: "I mean, who are these people… Why am I supposed to care about her anyway?"

Ware is anticipating his own readers' potential reactions. Building Stories may be the most concerted and apparently counter-intuitive attempt in any graphic novel to take us inside the life, thoughts and emotions of one fictional, unnamed character and make us care. That he succeeds, without the manipulative heartstring-tugging of cinema or theatre but with comics, is all the more remarkable.

Further insights are gleaned from two folded strips. In one, a repeated snowy street scene tops and tails a looping narrative as our freezing female lead bemoans the family she almost had; in the other, she strives to understand her growing daughter. Memories and imaginings are already blurring; she later reflects how events which never happened can be "almost as real to me as memories."

Other characters, such as the landlady and the iconic bee from the lid, get their briefer turns in the spotlight. Branford the Bee tells his life from his entomological understanding, so humans are giant pink land-whales, glass is hard air and his faith in God, whose eyes are the flowers he licks, is almost unshakeable. However deluded, he seems the most contented with his lot.

A board-book with a gilded spine, evoking America's Golden Books for children, provides a time and place: 23 September 2000 and a three-floor, 98-year-old Chicago apartment building, which observes events across that single day. We are told that the building, "accidentally catching a glimpse of itself in the glint of the windows across the street, sighed."

Building Stories is a book of sighs, of characters looking at themselves in disappointment, if not despair, as they struggle with unfulfilling lives, unrealised dreams, unrequited loves, yet finding something, however ephemeral, to help them build their stories. When the florist finally holds hands with a potential boyfriend, she writes how "a time-lapse tulip bloomed in me, somewhere in the vicinity of the lower abdomen."

Earlier, as an art student, she struggled to explain her paintings: "I guess they're about the intersection of loss and recognition... and the spaces we create to negotiate them". She could be summing up Ware's main theme in Building Stories. In the organising of time into space in comics, nothing disappears; every moment has its space, like a row of photos on a shelf, or the set of comics housed in this box.

We can turn back the pages and find one again, much like the way our brains can access a memory. One episode set in her childhood bedroom ends with her falling asleep as she remembers where three earlier versions of herself were sleeping in the same room, "because it helps me keep all the pieces in place."

Paul Gravett is the author of '1001 Comic Books you must read before you die' (Cassell Illustrated)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments