Book review: Fire and Ashes: success and failure in politics, By Michael Ignatieff

An idealist reflects on the seduction of politics – and his failure to make a mark

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."I want to explain how it becomes possible for an otherwise sensible person to turn his life upside down for the sake of a dream, or to put it less charitably, why a person like me succumbed, so helplessly, to hubris." In some ways Michael Ignatieff is too hard on himself in this brutally frank and at times self-lacerating book.

The disastrous engagement with front-line Canadian politics that he chronicles was not his own idea. When, one night in October 2004, three "men in black" arrived in Cambridge, Massachusetts with the proposition that Ignatieff should consider leaving Harvard, where he had a chair at the Kennedy School of Government, and return to his native Canada to lead the Liberal Party, he found the idea scarcely credible.

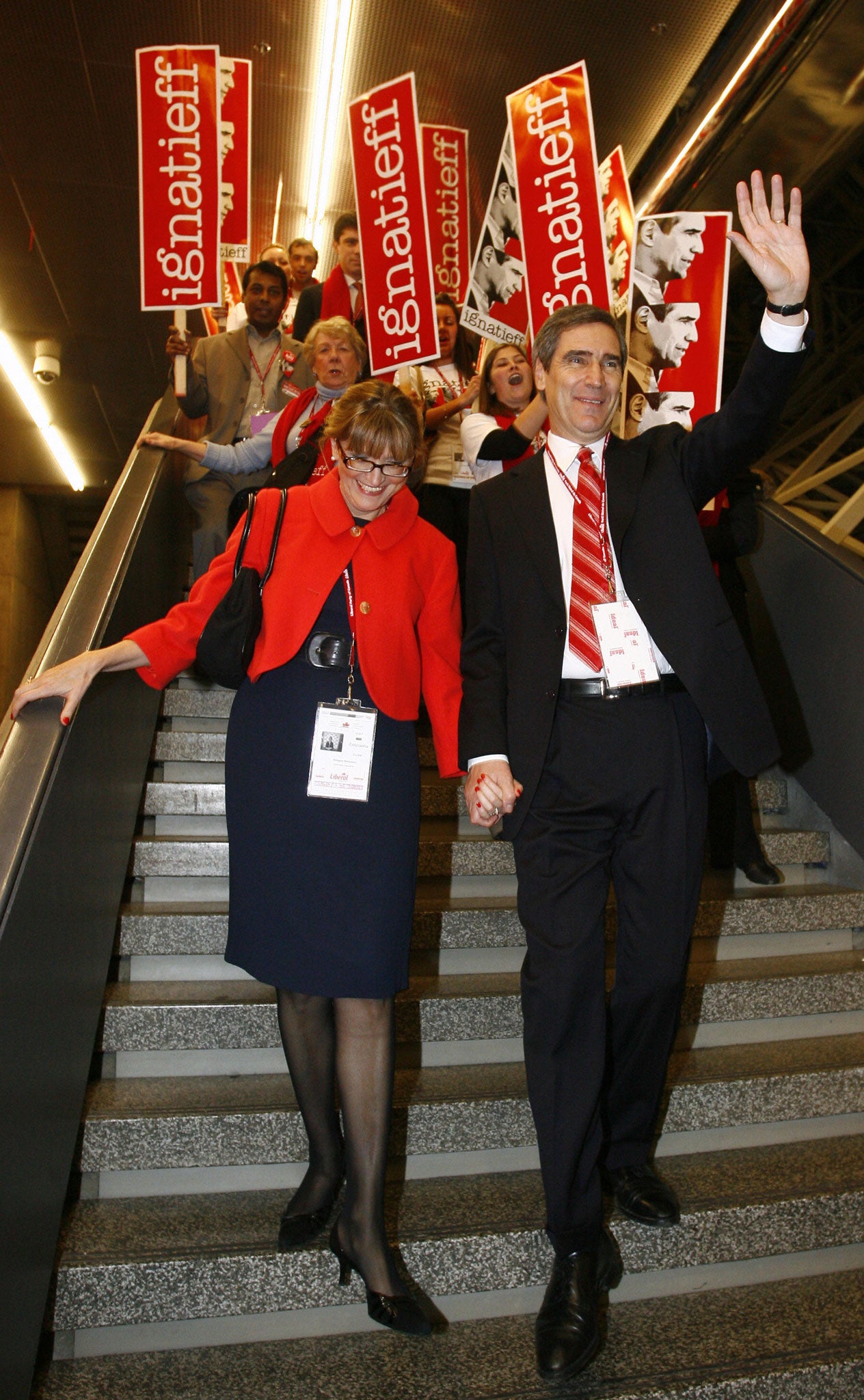

Yet he had to admit it had its charms. He had "always admired the intellectuals who had made the transition into politics – Maria Vargas Llosa in Peru, Václav Havel in the Czech Republic, Carlos Fuentes in Mexico". True, many of these intellectuals had failed. In any event, he reflected, he "wasn't exactly in their league". But the three visitors – whom Igatieff identifies and describes vividly – made it clear they wanted to make him Canadian Prime Minister, an offer fraught with danger but too powerfully seductive to be turned down. "Soon afterwards, and against the better judgement of some good friends, I said yes to the men in black… I pursued the flame of power and saw hope dwindle to ashes."

Ignatieff tells us he and his wife, Zsuzsanna, were happy at Harvard. So why overturn a secure and fulfilling career as an academic for the conflicts and uncertainties of politics? It seems he still does not understand why he did it. Hearing the offer, what should have welled up inside him, he tells us, was laughter. "The idea was preposterous."

He never tells us exactly why the idea was so ridiculous. Ignatieff's candour has its limits, particularly when it comes to admitting facts that virtually guaranteed the failure of his foray into politics. One, which he discusses at some length, was his long absence from Canada, first in Britain as a fellow at King's College, Cambridge, and later journalist, novelist and television personality, then as an academic at Harvard. It was inevitable that he would be dogged by the accusation of "just visiting", for the sake of political ambitions, a country in which he had shown no great interest for many years.

Another factor, which he barely mentions, was his never retracted support for the war in Iraq. Of all the cheerleaders for that predictably ruinous venture, Ignatieff was among the most wildly deluded. Writing in the New York Times in January 2003, before the US-led invasion, he waxed rapturously on America's "21st-century imperium, a new invention in the annals of political science, an empire lite, a global hegemony whose grace notes are free markets, human rights and democracy, enforced by the most awesome military power the world has ever known".

Hindsight isn't needed in judging this to be a fantasy of Blair-like proportions. There were plenty of people, in various branches of American and British government and in the armed forces of the two countries, who were extremely leery of militarily enforced regime change and presented cogent arguments to their political masters against any such intervention. Of course, these voices of reason were over-ridden or disregarded, and later the whole mess was blamed on too little forethought about what the country would be like after the invasion. The truth is that, if there had been any serious forethought, the invasion would not have been launched. The blame for the gruesome fiasco that followed falls squarely on the shoulders of those who banged the drum for war.

For perhaps the first time in the history of government, this was a war driven chiefly by intellectuals – and not only by neo-conservatives. Many liberals succumbed to the fantasy of America's omnipotence. Presciently exposed by Paul Kennedy in The Rise And Fall Of Great Powers (1987), the US was in reality an imperial power in decline and seriously over-stretched. But in the feverish atmosphere that prevailed after the end of the Cold War, reality-based thinking was not in vogue. Though you would never know it from this memoir, Ignatieff was one of the most prominent and influential of those who embraced the fashionable idiocy that the world could be remade by American power. The voters of Canada, however, had not forgotten.

Ignatieff's experience of rejection has left him feeling ambivalent in his attitude to the politician's trade. Defining politics as "a charismatic art", he notes with some exasperation how today a politician's life often seems little more than performing in an unending "reality show". His remedy is another dose of inspirational rhetoric: we must "think of politics", he writes, as "a calling that inspires us onward, ever onward, like a guiding star". In urging as the solution for our problems a burst of moral enthusiasm, he is echoing virtually every politician in the western world. Embarrassing guff of this all too familiar kind will do nothing to diminish the contempt in which politicians are currently held.

Yet almost despite himself, Ignatieff does have something important to teach us. The practice of politics is an intrinsically chancy and even treacherous business – "a supreme encounter between skill and willpower and the forces of fortune and chance", very much like war in being a dangerous art in which there are "no rules, only strategies". This is good advice for any budding politician.

In being seduced by the men in black, Ignatieff was reacting as any high-minded, ambitious and self-deceiving person would do in the circumstances. Imagining he could triumph over his past and conquer a country he no longer knew or understood, he embodied the ruling cliché of the age: the belief that smart thinking and good intentions can overcome almost any obstacle.

Yet in Fire And Ashes he presents a defence of politics that cannot be ignored. Rather than scorning politicians, it would be more sensible to lower our expectations of what politicians can hope to achieve. If not the lesson he would like to take from his experience, this is the true moral of the story that Ignatieff tells.

John Gray's most recent book is 'The Silence Of Animals' (Penguin)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments