Book of a lifetime: Brave New World, by Aldous Huxley

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I first read Brave New World in 1949. I was a frivolous 18-year old studying economics at St Andrews. There had always been favourite books.

I'd grown up with Tolkien's The Hobbit, moved on to the homoeroticism of EF Benson's David Blaise, then to the bodice-rippers of Georgette Heyer and the fierce socialist indignation of Upton Sinclair in The Octopus.

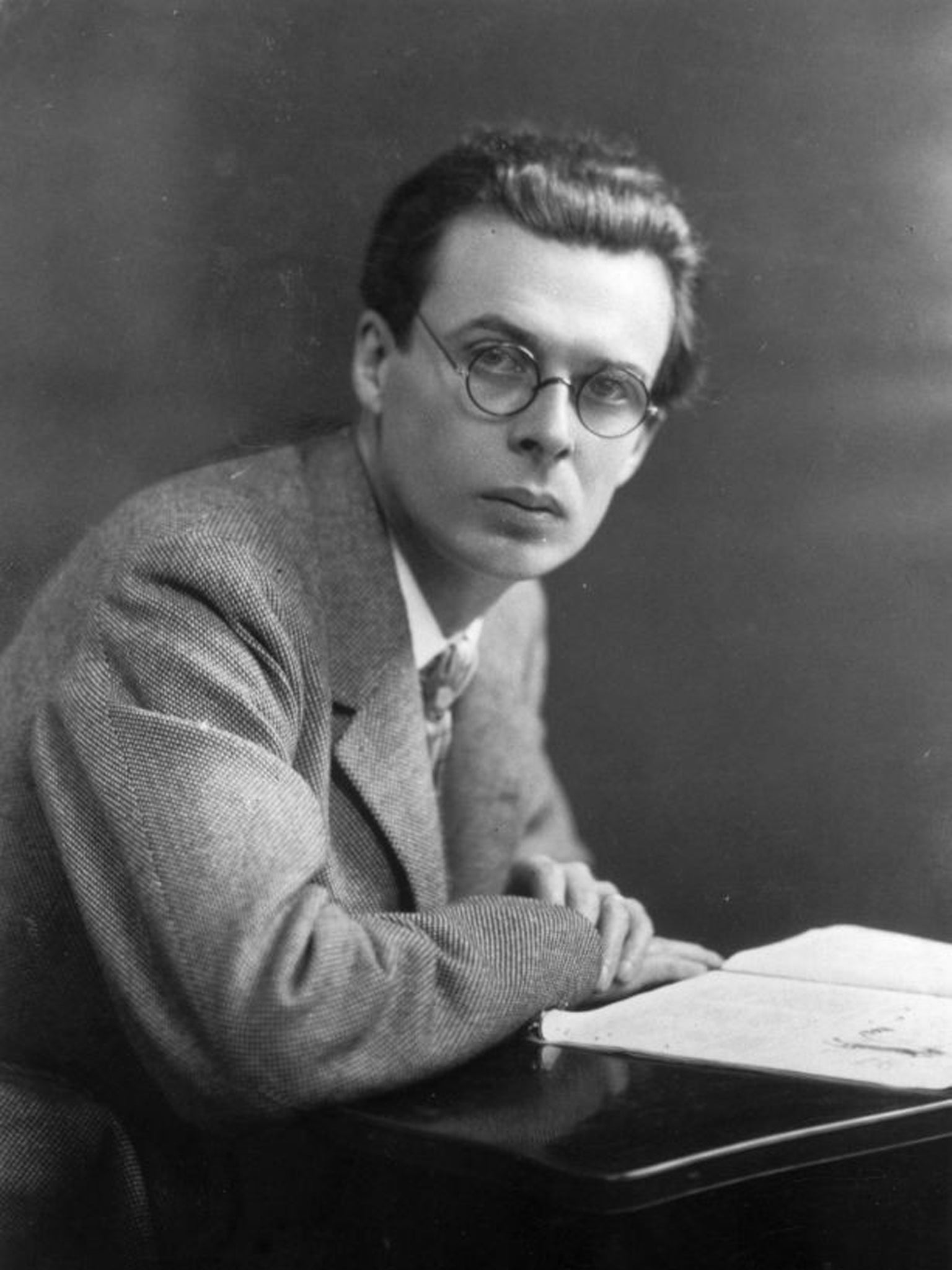

I rested a while on the calmer Fabian shores of Shaw's The Doctor's Dilemma and Wells's Anne Veronica, when my fictional world was suddenly illuminated by the sensuous sophistication that was Aldous Huxley. First Chrome Yellow with its arcane classical and cultural references, then After Many a Summer, with its warring philosophies posing as characters, and then, triumphantly, Brave New World, Huxley's great prophetic masterpiece, a literary lesson in how to get away with social comment (which is what readers hate and writers love) if only you have a strong enough plot.

We're in a future society controlled by genetic technology and the tranquillising drug soma. Huxley saw it as a dystopia; I fear the contemporary reader tends to see it as a Utopia. There is complete sexual freedom, no illness, no distress, no neurosis, no art, and above everything, no mothers. All babies are hatched, graded and grow up content, mind-controlled, happily accepting their position in society. Alphas are tall, bright and beautiful and run everything; epsilons, short and plain, clean up. Others take their place in between. Graded, in fact, rather as the BBC now grades class from the élite to the humble precariat.

Bernard our hero is an Alpha, but "something went wrong with the mix", so he is shorter, more nervous and wilful than he ought to be; sexually jealous, almost unhappy. Bernard of course is Aldous, a short-sighted nerd born into the spectacularly successful family of scientific and literary Huxleys. Another lesson, in how to be in a novel and pretend not to be.

"Poor Aldous", my mother dismissed him – she moved in the same circles when a girl. "He was so very plain. Those pebble glasses and those teeth – and always trying to prove he knew more than anyone else." Hence the obscure references, the determination to know better than his readers, which does tend to blight some of the work. My mother, when she herself published a romantic novel, was appreciative enough to steal her nom de plume Pearl Bellairs from the annoying romantic novelist in Chrome Yellow, and lived in guilt and fear of discovery for the rest of her life.

The first two books of Fay Weldon's 'Love and Inheritance' trilogy – 'Habits of the House' and 'Long Live the King' – are published by Head of Zeus

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments