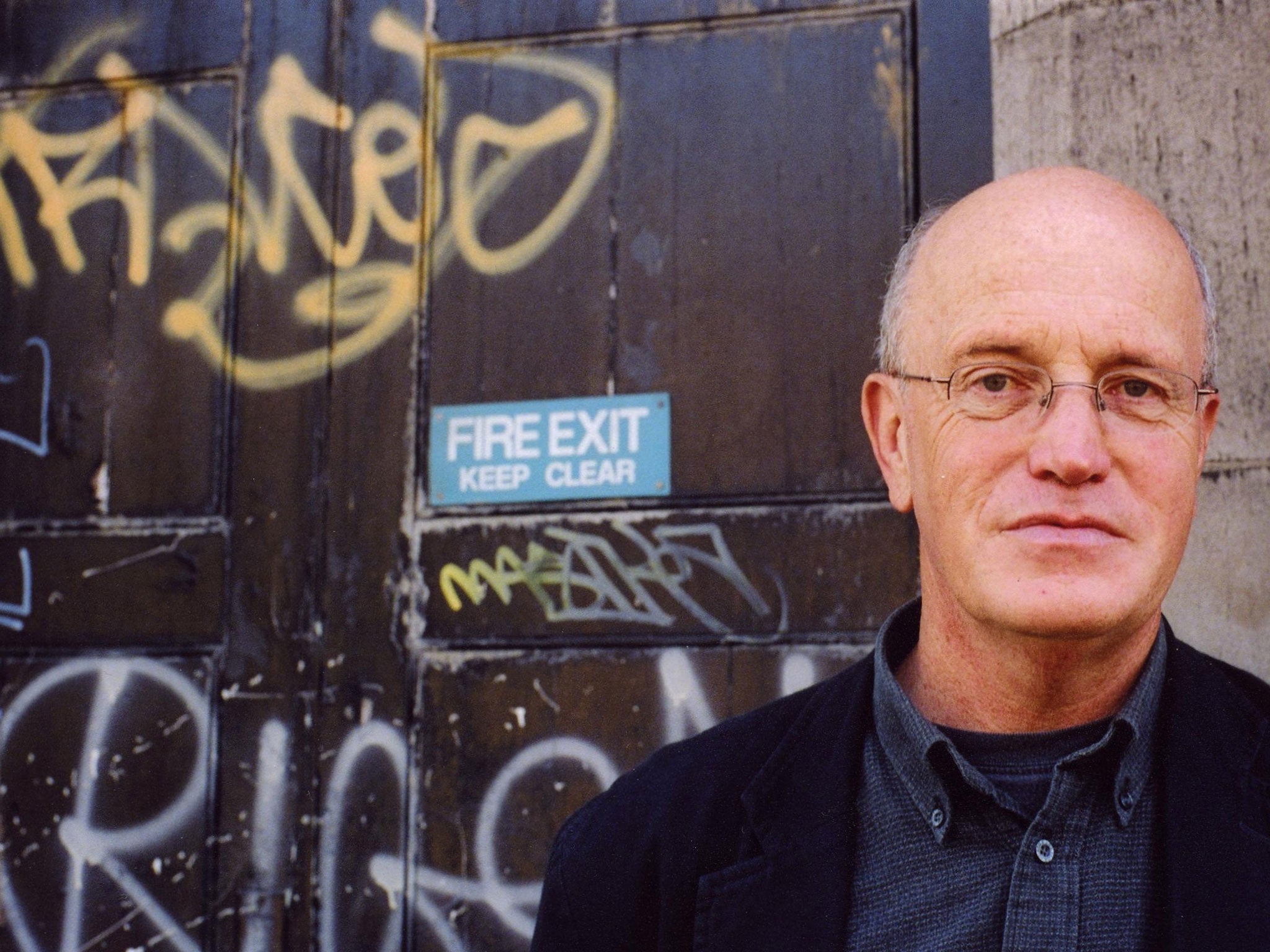

Black Apples of the Gower by Iain Sinclair, book review: A wondrous journey through mystic Welsh locations

In his second book of 2015, Sinclair travels back to his origins in Horton, a "village on the edge of amnesia" on the Gower coast in Wales

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At 72 years old Iain Sinclair shows no sign of slowing down, either as an author or filmmaker; this is his second book of 2015. He would probably smile wryly at his activities being described as a literary career; nevertheless, if the word is used as a verb, meaning ‘to move swiftly and in an uncontrolled way’, rather than as a noun, the description fits. Much of Sinclair’s best-known writing is a one-man infantry charge generating a stream of prose, partitioned between different covers but really part of one vast meta-book, or map, of a territory that is as much mental as physical. Movement is the method: one kind of career begetting another.

Despite his continuing momentum, Sinclair has taken time recently to revisit his past in an apparent desire to sum up the journey so far: the year-long film season and accompanying book 70 X 70 marking his 70 birthday and the return to his youthful obsession with the Beat poets in American Smoke are two examples of this elegiac tendency.

With Black Apples of Gower the author is travelling even further back in time, to his origins in Horton, a ‘village on the edge of amnesia’ on the Gower coast in Wales. Gower, Sinclair explains, sees itself as a severed English community stuck on the wrong side of the Bristol Channel. Sinclair, who had his Welsh accent bullied out of him at public school in Cheltenham, is therefore a kind of double outsider, at home neither side of the border: perfect qualification for a professional chronicler of London.

He has done this coastal walk twice before: once as a 16 year old with his mates, on the lookout for likely girls; once as a 29-year-old avant-garde poet, accompanied by the artist and writer Brian Catling. Returning to the landscape of his childhood, long schooled in the ‘murky elsewheres’ of the city, Sinclair worries he won’t ‘have the words, the technical terms, for the natural forms’ that surround him. Gradually, as he and his wife walk the path, his Welsh mojo reignites and the cliffs and seascape are summoned up in hallucinatory vividness, in between digressions on the poet Vernon Watkins, William Blake, Dylan Thomas and the art of Ceri Richards, whose image of the legendary apple is ‘a nimbus of darkness… an exposed cavern’, and gives the book its name.

An objective emerges: to reach the Paviland Cave, a Palaeolithic burial site which has eluded him on previous expeditions, from where the so-called Red Lady of Paviland, a prehistoric skeleton, was plundered by a deranged 19 century Anglican priest named Buckland in 1823. His goal is reached through a chance encounter with a young woman, ‘her hair in a pigtail, Native American fashion’, whose name is an echo of his wife’s and whose partner happens to be an author on pagan Britain.

The synapses of Sinclair’s books fire on such coincidences. The perilous descent towards the cave reminds Sinclair of a dream he recorded in a book years previously, its ‘entropic vision’ leaking into the present. Once achieved, the cave’s interior defies interpretation: instead, we are told in italics, ‘what happens is recognition as a form of possession’.

These mystic locations then, fragments of embodied meaning, sought in the occult alignment of Hawksmoor churches or the retraced footsteps of long-dead poets, were built into his beginnings, there from the start. Confronted with a photograph of an eleven-year-old version of himself, Sinclair claims ‘no part of that boy-person is available’. Of course, the reverse is true: you can take a boy out of the Gower, but you can’t take Gower out of the boy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments