Bernard Buffet: the Invention of the Mega-artist by Nicholas Foulkes, book review: Paris prodigy turned pariah

Painter Bernard Buffet's fame rivalled that of Picasso - until his fortunes changed

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The case of Bernard Buffet is somewhat unique. Born in 1928, his adolescent years were spent in Nazi-occupied Paris, a time characterised by blackouts, curfews and the lack of the most basic commodities.

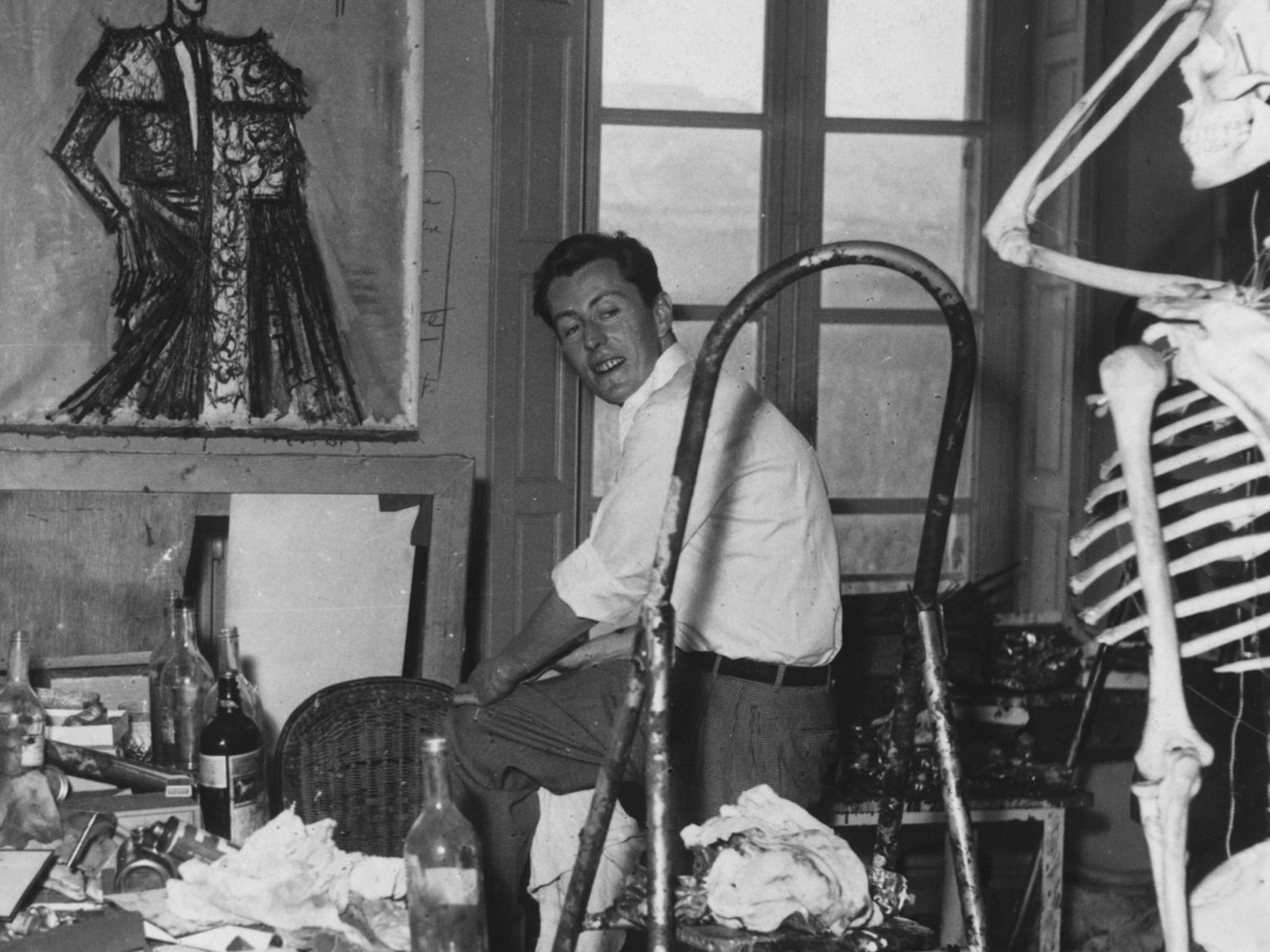

A failure at school, he began attending evening classes in drawing and showed such talent he was allowed to enrol at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts at the age of 15. By 21, he was a superstar with Paris at his feet, his work collected by Hollywood actors, his name linked in the press with the other young vedettes (celebrities) of the day and his fame frequently compared in the press to that of Picasso.

Yet before the 1950s were through, despite amassing fabulous wealth, he had fallen from favour with the art establishment and never regained credibility in his home country. How, the author asks in this authorised biography, could this have come about so swiftly?

The answer, unfortunately, is not hard to find. Despite beginning his career as the epitome of bohemian cool – young, bisexual, with angular good looks – Buffet swiftly morphed into a bloated and reclusive dipsomaniac, producing a vast number of paintings, many of them unequivocally bad: mawkish clowns, flowers, cars, touristic scenes and endless still lives. Perhaps the more interesting question is how he achieved the degree of success he did in the first place. What was it that the French public and art market needed at the time of his ascendancy and how did he provide it?

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, the centre of the art world moved from Paris to New York, along with those European artists who fled the advancing war. Picasso, the city's remaining resident artistic deity, had made the great anti-war statement in Guernica, but who would now paint the peace?

Buffet's post-war Paris was instantly recognisable, a place peopled by stick-thin inhabitants pictured, often naked, in Spartan interiors alongside toilets, baths and bidets. This was a world the existentialists could subscribe to, signifying nothing other than itself. Buffet, paint-splattered and taciturn with an ever-present cigarette dangling from his lip, played the part of the outsider artist to perfection. France was entering a period of economic revival – Les Trente Glorieueses – and a moody Buffet oil was the perfect way to accessorise a chic apartment, his prodigious output a guaranteed source of supply for new investors entering the market.

As Buffet's financial status changed, so did both his image and his subject matter. Groomed by his lover Pierre Bergé, he took to wearing expensive clothes that set off his film-star good looks. At first the public was charmed, but a photograph of the suave young artist being handed into his new Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost by his uniformed driver turned the tide against him.

Living in isolation in a series of majestic country piles, ignorant and dismissive of the contemporary art scene, he had no one to challenge the direction he was taking. While he undoubtedly had graphic skill he lacked the vital ability to edit: he claimed in the 1990s to have finished a painting every day since 1946 and his gallerist did nothing to stem the tide.

After Bergé ran off with Yves Saint Laurent, Buffet married his second wife, a nightclub singer and fellow alcoholic; they drank heavily, becoming convinced Buffet was excluded from critical acclaim by a cabal at the top of the French art system, a conspiracy theory the author somewhat uncritically buys into. "All the museums in France are closed to me. The intelligentsia does not appreciate me. The public really like me" Buffet claimed, in one of many variations on a theme, and it was true that he was hugely popular, his clown pictures in particular endlessly reproduced as posters, his sales in the French provinces, in Japan and other emerging markets unaffected by critical opinion in the capital.

Foulkes does his best to muster dissenting voices, leaning heavily on a couple of off-hand remarks by the ever-ironic Andy Warhol, and pokes fun at the jargon of contemporary art criticism, but neither his claims for Buffet's influence nor for his status as a precursor of the media savvy mega-artists of today really hold water. Instead we have a thoroughly researched account of a life tinged with sadness, spent mostly in the studio, compulsively painting: Buffet, the reader suspects, would have been there anyway, whether the gods of fame and fortune came to visit or not.

Preface, £25. Order at £21.50 inc. p&p from the Independent Bookshop

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments