Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph by Jan Swafford, book review: How the composer's music gave voice to every human experience

One of the pleasures of Jan Swafford's magisterial, warm, and engaging biography of Beethoven is to read his writings on the individual pieces that made up this "piano-composer's", then Tondichter's ("tone poet"), incomparable oeuvre whilst having recordings or scores to hand.

There is enough to satisfy music experts and to enhance the keen lay reader's appreciation of form and craft, the characters of different keys, the pioneering expanding of all a sonata or symphony, concerto or string quartet could be, the respectful nods to the inspiring (and potentially overbearing) legacy of Mozart and Haydn, the galant style of the 18th century and the prophetic look ahead to the incredible leaps audible from the earliest trios and sonatas issuing from Beethoven's pianoforte and work-table by it, the importance of the "unity of the whole" as ideas took shape in his sketchbooks and on his daily walks, his head singing with music, from his days of immaculate hearing to the slide into almost complete deafness and the other serious ailments besetting his body even as he longed, in a letter to one of his dear Bonn friends, "to live a thousand lives", aware of the beauty and joy of life and full of the Aufklärung's (German Enlightenment) optimism for the potential of humanity.

This is nowhere heard more clearly than in the choral entry of his Ninth Symphony in which the poem by Schiller An die Freude (Ode to Joy), a companion in his thoughts from a young age, finds its glorious release, a call to all humanity, impossibly poignant in the police state Metternich's Austria had become after the Congress of Vienna in 1814, and still now.

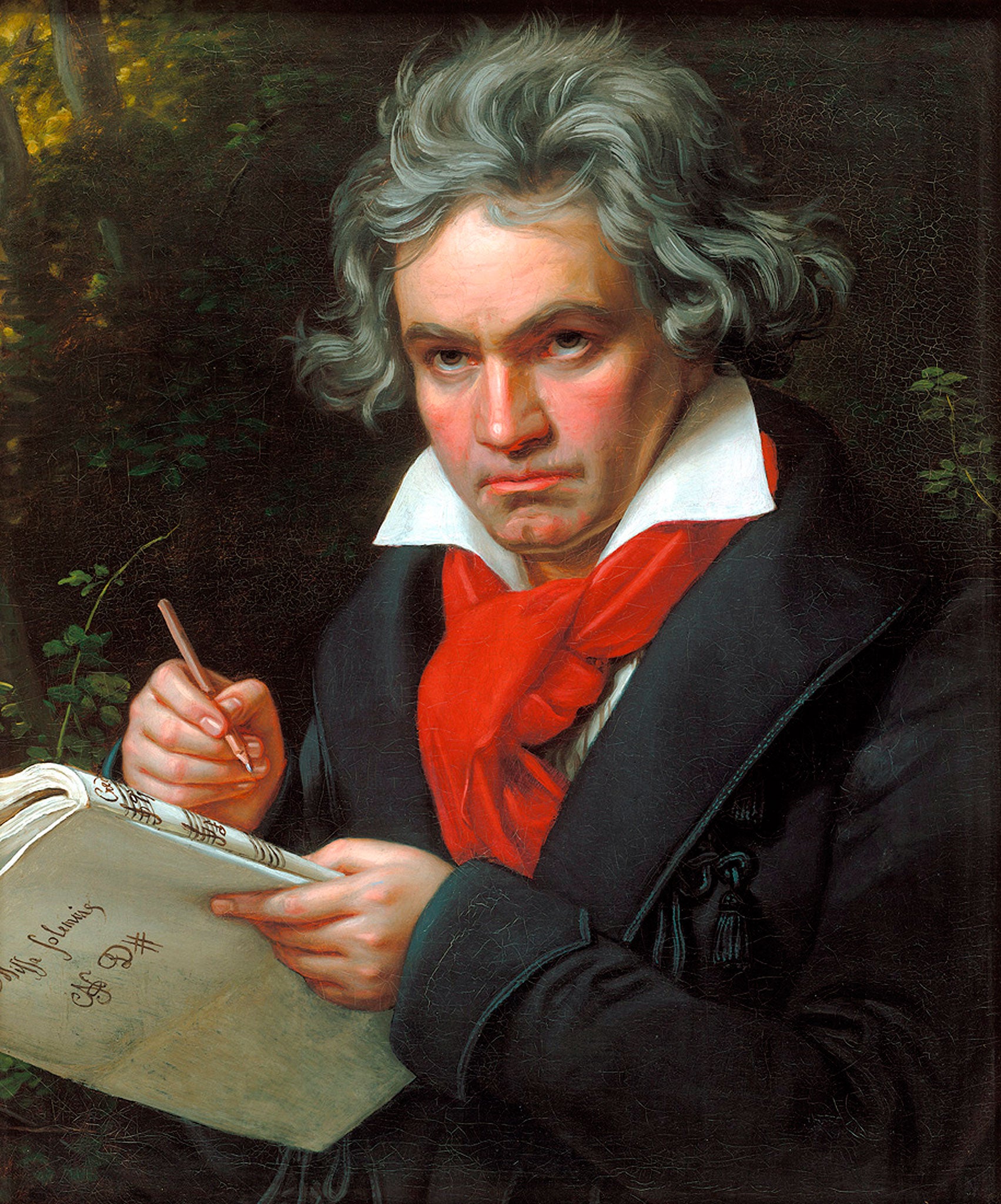

Swafford's invitation is to regard Beethoven the man and artist, not the myth and stuff of legends, to listen to his music with more intimacy, to think of him not as a revolutionary (his politics were not), but as a "radical evolutionary with a unique voice", a man living in intensely interesting times, one of the trio of German giants straddling the 18th and 19th centuries (along with Kant and Goethe), forming a bridge between Enlightenment and Romanticism, a finger on the pulse of political change and its ramifications, but entirely himself, aware of his tremendous strengths and flaws, who in the course of his life (1770 – 1827) gave voice as never before to the palette of human experience, tenderness, wistfulness, rage, wild joy, dark despair, hopefulness, love, pain, loneliness, playfulness placing considerable demands on musicians and listeners, refusing to simplify and never feeling he had accomplished all he should have.

Occasionally in letters he would voice the struggle of fulfilling an artist's potential, as here to a young admirer, an example of his generosity and kindness, aspects given short shrift Swafford muses, focus given rather to his temper and curmudgeonly aspects: "The true artist has no pride. He … has a vague awareness of how far he is from reaching his goal; and while others may perhaps admire him, he laments the fact that he has not yet reached the point whither his better genius only lights the way for him like a distant sun."

The biography leads us through from Beethoven's formative years in Bonn, the joie de vivre of the Rhineland of the "benevolent despot" Archbishop Electors with their passion for education and music, his Freemason mentors nurturing more kindly the talent his dissolute father recognised, to Vienna and teacher Haydn, a city of music-obsessed aristocracy (his patrons) wowed by the virtuosic piano-playing of this rough diamond. He never cared much for Vienna, but found peace in its woods and stillness, his religious feelings joined to Nature not dogma. Against, then, a backdrop of Napoleonic wars, a portrait of a man with "near as much courage as a human being can have" emerges. A triumph of scholarship and musical affinity... Jan Swafford is to be saluted.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments