Babylon, By Paul Kriwaczek

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

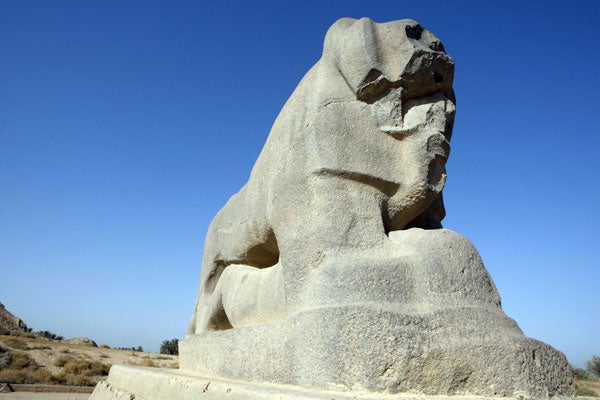

Your support makes all the difference.As part of his personality cult, the late President Saddam Hussein of Iraq liked to advertise his powerful affinity for the heritage of ancient Mesopotamia. Saddam launched a grand reconstruction of the site of Babylon as he visualised it at the time of its ruler Nebuchadnezzar (605-562 BC), using bricks inscribed with the names of Nebuchadnezzar and himself in modern Arabic, rather than original Babylonian cuneiform. For the International Babylon Festival in 1990, he invited cabinet ministers, officials, diplomats and international reporters to celebrate his 53rd birthday in his home village. The climax involved a wooden cabin, wheeled out before crowds dressed in ancient Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian and Assyrian costume, who prostrated themselves. Inside was a palm tree from which 53 white doves flew up into the sky; beneath them a baby Saddam, lying in a basket, came floating down a marsh-bordered stream.

"Moses redux", wrote a reporter from Time. But why would Saddam wish to compare himself with a Jewish leader? In fact, the dictator "was alluding to a much more ancient and, to him, far more glorious precedent", Paul Kriwaczek observes in Babylon, his history of three or four millennia of Mesopotamian civilisation ending with the arrival of Alexander the Great (who died in Babylon in 323 BC).

According to his legend, Sargon – the great king of Akkad in the late third millennium BC - was born of lowly origins and abandoned in a river (presumably the Tigris or Euphrates) by his mother. Rescued by a drawer of water, the orphaned baby became a gardener and founder of the first true Mesopotamian empire, that of the Akkadians. It went on to have a complex relationship with the later, and more southerly, Babylonian empire.

The lively mixture of topicality, politics, history, myth and culture in this anecdote is typical of Babylon at its best, and distinguishes it from a long-established book with a comparable general readership: Ancient Iraq by Georges Roux. This is not surprising, since Kriwaczek was for 25 years a journalist and producer for the BBC World Service, who worked in the Middle East and Asia and is fluent in eight languages. Although he cannot read Babylonian cuneiform - one of the more challenging scripts of antiquity - his research is solidly based and up to date, without allowing archaeologists' natural caution to diminish the book's readability and willingness to hazard informed conjectures.

Kriwaczek seldom lets us forget how little is known for certain about ancient Mesopotamia, even after a century and a half of digging. Many of the recognised sites have still to be excavated, assuming they have not been looted since the war of 2003. Only a fraction of the million or so cuneiform documents in museums have been fully deciphered. We still have no reliable idea of how the first city, Eridu, came into being before 4000 BC in the deep south of Mesopotamia near the sea; nor of how writing was invented, probably in Uruk around 3300 BC.

Somewhat less successful are Babylon's intermittent attempts to draw conclusions about what is meant by "civilisation". The familiar idea is that cities, and thus civilisation, began in Mesopotamia. Yet with the city, says Kriwaczek, came the centralised state, the hierarchy of classes, the division of labour, organised religion, monumental building and civil engineering. Fair enough. However, he also claims for the city the beginning of sculpture, art and music, not to speak of education and mathematics. None of which is really defensible - certainly not the claim for art, given the far older cave paintings of prehistoric Europe.

Much of the book inevitably concerns war between city states, including that of the notoriously brutal Assyrians based in Ashur. Surely war, too, must belong in any list of civilised behaviour arising from the Urban Revolution? Sometimes Kriwaczek includes war, at other times he does not, even writing that "Akkadian hero culture valued civilization as highly as war". This is a fascinating and hugely topical debate. If nothing else, Babylon's discussion reminds us of the discouraging fact that wars have been taking place in Mesopotamia for at least 5,000 years.

Andrew Robinson's 'Sudden Genius? The gradual path to creative breakthroughs' is published by Oxford in September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments