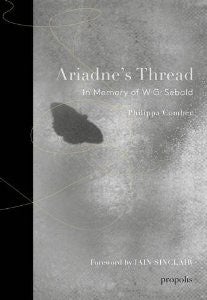

Ariadne’s Thread: In Memory of W G Sebald, by Philippa Comber - book review: Engrossing portrait of the connoisseur of loneliness

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.W G Sebald, the German scholar-writer, died in his adopted East Anglia in December 2001. He was on the cusp of international recognition when, driving on the A146 from Norwich to Lowestoft, he suffered a heart attack and died in a head-on collision. Readers of all ages and nationalities now find themselves mesmerised by the luminous blurring of fact and fiction in Sebald’s work. Vertigo, The Emigrants, The Rings of Saturn and Austerlitz are uniquely strange prose fictions, which belie a fascination with the past, and the pain of remembering it.

Ariadne’s Thread, an absorbing amalgam of memoir and biography, recollects the Bavarian-born author in all his melancholic humour and habit of solitude. Philippa Comber got to know Max (as friends called him) in the 1980s when she ran a psychiatric day centre in Norwich. He had worked as a university lecturer in England since his mid-twenties, and was, it seems, looking for companionship. He and Comber began to court each other in a decorous way. To haunting effect, Comber quotes from diaries she kept at the time (“perhaps I’m falling in love with him…”)

A connoisseur of loneliness, Sebald speaks to her of his sense of cultural displacement and autumnal sense of loss at leaving Germany in the mid-1960s. An inveterate collector of things, his habit was to trawl East Anglian junkyards and second-hand shops for photographs, postcards and other nostalgia-inducing detritus. Sebald’s instinct to collect was perhaps a way to compensate for what had been lost at home in Continental Europe.

His fiction, with its captionless photos of people and places, explores the moral amnesia that descended on post-war Germany. Comber speculates that the writer’s father Georg Sebald might have been a “passive collaborator” in the Nazi regime. Certainly father-son relations were strained. In his great essay, “An Attempt at Restitution”, Sebald relates how his father came home as a stranger in 1947 from a PoW camp in France and said absolutely nothing about the Hitler war.

We learn much about Sebald’s foibles and enthusiasms. Mindful of his appearance, he carried a little moustache brush in the pocket of the brown tweed suit he sometimes wore (“cuts quite a dash”, Comber notes.) Comber sees “Max” as a saturnine, even depressive figure, who wrote of the travails of walking and literary wandering in a vein of cypress-dark melancholy. Pathetically, his dog Maurice led the small funeral procession to the site of his grave, “and, shortly afterwards, also died”. Comber’s exquisitely written book confirms Sebald as one of Europe’s most mysterious and best-loved literary imaginations.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments