Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Some stories are delightful when they are told well, no matter how often we have heard them. The patient man is driven to become the hero; the villains will fail because they cannot stop over-reaching. Both of these say something about what it is to be human, to have limits and to make choices. The same is true of the story of the weapon too dreadful to use, or the knowledge that our minds cannot hold and remain sane.

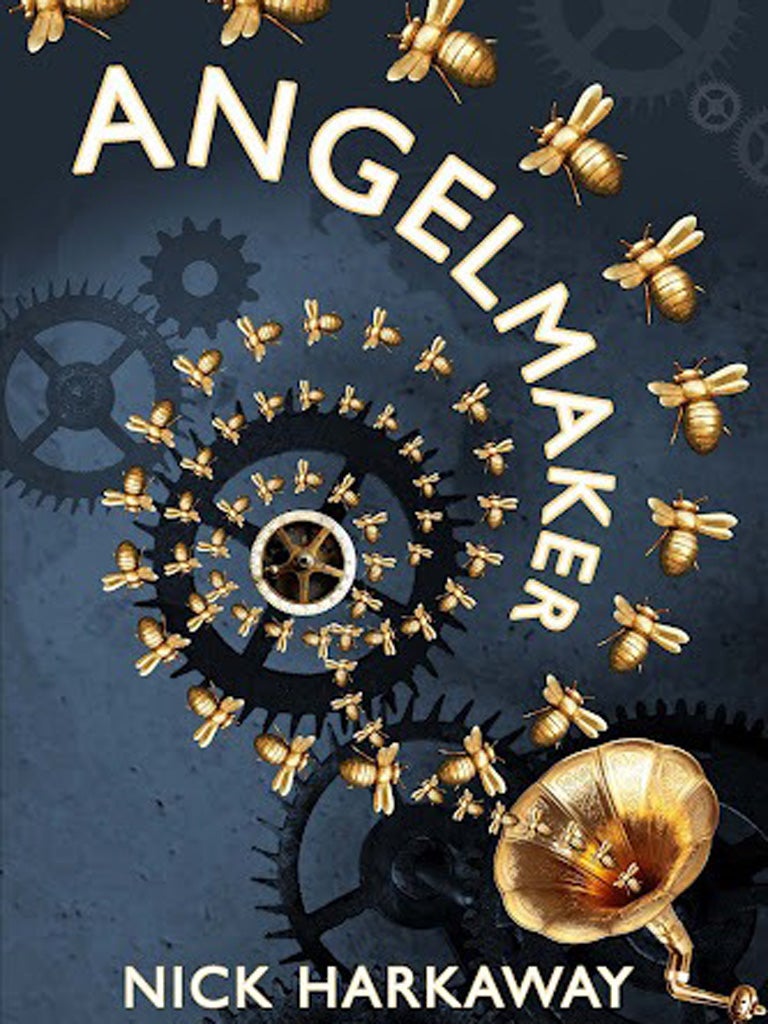

In Angelmaker, clockmaker Joe is the son of a gangster whose Tommy gun ruled London crime, and the grandson of a bisexual scientist whose gadgets, she estimated, turned the tide of the Second World War a fraction. Joe has tried to set his legacies aside and just work with his hands. Then he mends the wrong arcane gadget, and his life turns to hell, pursued by the organs of the state and a mysterious cult of veiled men.

Meanwhile, aged superspy Edie Bannister remembers her glory days. She has her reasons for putting Joe in harm's way. She spent her career fighting Shem, the opium khan, and thinks him long dead; yet the men in veils walk and fight like him.

Nick Harkaway's first novel, The Gone-Away World, was about surviving the end of everything. His second is about preventing it; it has heroes and villains that are archetypes and yet specific. Harkaway's brilliance in this novel of adventure, love and intrigue is that he enjoys these stories and makes us remember how much we enjoy them. There is the stuff of nightmares here, but told in a light-hearted way that makes the reader grin with pleasure. It is also a fascinated homage not only to the pulp fiction of the past but also to a lost alternate England of craftsmanship: fast steam trains and back-room boffins whose gadgets beat fascism.

This is a complicated story in which every single detail is there for a reason, yet it has a heart. Harkaway gives us escapes that are exhilarating and romances at once tender and sexy. Its villain is a fascinating monster of the old school, given new access to power by ruthless bureaucrats. It gives us a London where every alley is a path to danger, every tunnel a cave of miracles. Harkaway has given us, for the second time, a box of delights.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments