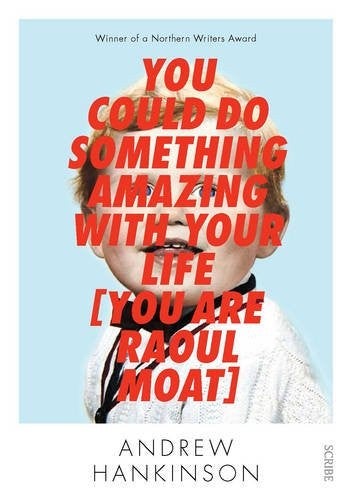

Andrew Hankinson, You Could Do Something Amazing With Your Life: 'Inside the mind of a pariah on the run', book review

Andrew Hankinson eschews those conventional approaches and tells the story as narrative non-fiction relayed in the second person

Raoul Moat’s rampage in 2010 was horrifying yet strangely absurd. As he hid in the woods, Ray Mears was hired to track him, internet trolls praised him, David Cameron denounced him, and Gazza turned up at the scene with some chicken in a carrier bag.

With such bizarre elements, Moat’s case would be a novelist’s or biographer’s dream, but Andrew Hankinson eschews those conventional approaches and tells the story as narrative non-fiction relayed in the second person: “You have nine days and your whole life to prove you are more than a callous murderer. Go.”

This short, intense book is based on Moat’s letters and tape recordings, composed while he was a fugitive, plus transcripts of his various 999 calls, prison phone calls and a psychological questionnaire.

The reader is plunged into his frantic and confused mind and we begin with his release from jail in 2010 where, having served a sentence for assault, he immediately plots revenge against his ex-girlfriend Sam, her new partner, and the police, who he is convinced ruined his life with petty harassments and his recent imprisonment.

Amid the anger, we find a man who watched Mr Bean DVDs with his children, worked hard at his Mr Trimmit tree surgery business, underwent hypnosis to help him cope with being dumped, and fretted about getting old and having “nobody to cuddle in to”.

And while in hiding, rather than coping in the wild, he sends a friend to Tesco for toothpaste, burgers and “a bottle of Reggae Reggae sauce”. This is clearly not the Geordie Rambo we saw in the newspapers.

But despite these new insights, the book’s second-person narration imposes regrettable limitations upon itself.

It cuts out the strange aspects such as the involvement of Ray Mears and Gazza, because it’s restricted to what Moat knew and, unfortunately, Moat didn’t know very much. His mind, and therefore much of the text, is submerged in self-pity, paranoia and fantasy which quickly becomes repetitive, of interest to a psychologist perhaps but not to the common reader.

Other great works of true crime writing, such as Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song (1979) or Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (1966), unfolded to offer portraits of the victims, the town and the times, but this book’s narrative approach eliminates that prospect.

The author admits he has “edited and rewritten” some of Moat’s words for the sake of coherence, but often he inserts brackets in the text, like informal, embedded footnotes, which directly contradict or correct Moat.

So, when he casually says he “might hit or slap Sam” the bracketed text interrupts to say he also dragged her by the hair and throttled her.

This constant intrusion of the author dismantles the closeness to the subject which a second person narrative is designed to create. It’s like having a conversation with Moat while a lawyer stands by his shoulder shouting “objection!”.

Hankinson’s use of the second-person is a bold approach to crime writing but it doesn’t triumph with a subject who is so unreliable that he requires constant correction.

You Could Do Something Amazing With Your Life, by Andrew Hankinson. Scribe £12.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments