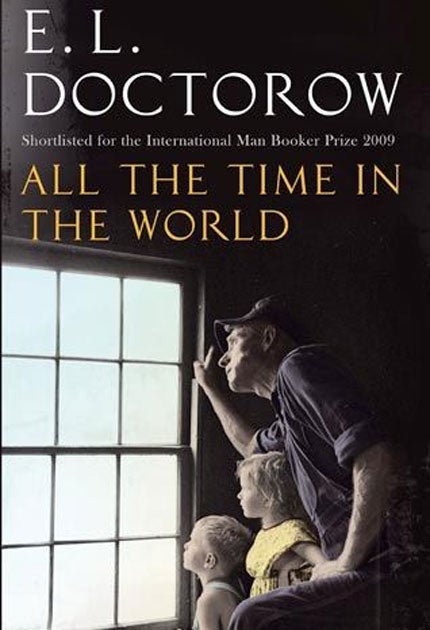

All the Time in the World, By EL Doctorow

A master falls short of his best

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the preface to his third collection of short fiction, E L Doctorow begins by defining the difference between writing novels and stories. The art of the novel is born out of "exploration", a kind of noble toil; while stories are "assertive... their voice and circumstance decided and immutable." It's a distinction that – perhaps without realising it – looks down the nose at the short form; snubbing it as merely transcription with a touch of linguistic spit and polish added for presentation's sake. This lack of full respect perhaps explains why All the Time in the World struggles to attain the penetration, menace and insight of Doctorow's celebrated novels.

In fact, the distinction is blurred by two stories here, "Liner Notes: The Songs of Billy Bathgate" and "Heist": the former a corollary to a full-length novel; the latter the starting point for City of God (2000). Both struggle to stand alone. In "Heist", the staccato, James Ellroy-style sentences are just beginning to reward the reader, and the narrative just proving interesting, at the moment the story judders to a close.

Many of these stories feel like truncated novels: line drawings that would work better as vast frescos. "Jolene: a Life" happily breezes through Jolene's romantic misadventures, never stopping to pause for reflection or rumination. Doctorow the novelist would have lent this material a deeper resonance; Doctorow the short-story writer just piles scene next to scene.

When Doctorow clearly sets out to write something specifically for the form, his stories are wonderfully deft, tightly constructed and gloriously dark. The opening story, "Wakefield", finds the eponymous character disappearing from his family home, only to live a scavenging life, hiding out in the attic space above the garage. Doctorow imbues the situation with humour and pathos, as well as fine, understated prose – the image of the sun shining through stained-glass windows, "setting a rainbow choker on her throat", is just one of many beautifully observed moments.

Similarly, "Walter John Harmon" – in which a lawyer gets sucked into a doomsday cult – and "Edgemont Drive" – a suburban mystery told only in voices – show Doctorow at his beguiling best. Ultimately, however, All the Time in the World is not consistent nor committed enough to rival novels such as Ragtime and The Book of Daniel.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments