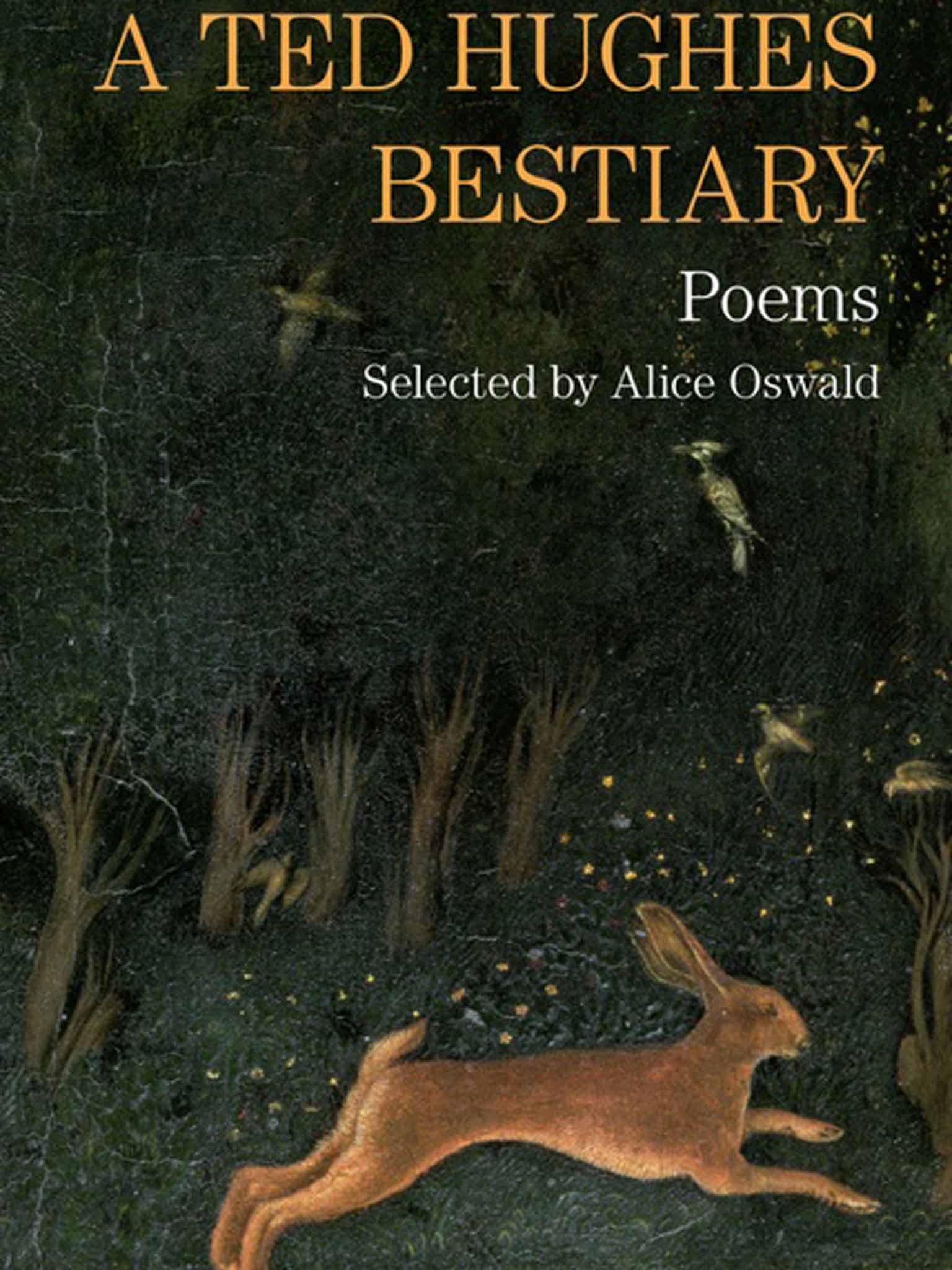

A Ted Hughes Bestiary: Poems selected by Alice Oswald - book review: Joyous, vigorous observations of the natural world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A Ted Hughes Bestiary is a thematic collection of 100 of the late laureate's poems. Hughes's animal poetry is arguably the joyous best of him, and is full of a country-dweller's lived experience. Whether a damselfly in "Performance", a "Midget puppet-clown, tranced on his strings, /In the nightfall pall of balsam", or the "plungings, and spray-slow explosions" of "A Dove", his creatures are completely, and delightedly, realised.

Country knowledge is built up through repeated encounters with beasts, both farmed and wild. This book is full of such encounters, from the famous dream of the "Thought Fox" that inspired Hughes's vocation, to a late "Epiphany" from Birthday Letters, in which he denies an orphaned fox-cub, himself, and his failing marriage by not taking the creature home.

These encounters aren't simply with animals but with wildness itself. Oswald's introduction suggests Hughes's language "embodies" his creatures. But the poems – whether the whimsical "The Lovepet", or the utterly un-whimsical "February 17th", about delivering a dead lamb – are not mimetic. They all use the poet's organic free verse and deeply musical speech.

Verbs describe large gestures; nouns are intensifiers that show off a wind's "long cat-gut cries" or a swallow's "knot of glittering voltage". It can seem astonishing that Hughes's poems are British, yet they are part of English tradition. John Ruskin described the six characteristics of Gothic art as "savageness, changefulness, naturalism, grotesqueness, rigidity and redundance". The beasts in this volume, both known and imagined, stunningly resemble the ones that throng mediaeval parish churches.

Like them, they are vigorous observations from the natural world, much of whose vigour nevertheless comes from symbolic distillation and exaggeration. For Hughes a trout in a canal, first "a brick… nearly as long as my arm", can become "A seed /Of the wild god now flowering for me". And his Wodwo, Crow, or Littleblood, "hiding from the mountains in the mountains /Wounded by stars and leaking shadow /Eating the medical earth", extend the physical and moral logic of the natural world, just as mediaeval manticores and gryphons did.

In her introduction, Oswald argues that Hughes celebrates immediacy of experience, whereas mediaeval bestiaries distanced that experience by organising it as symbol. Yet humans are meaning-making creatures. Surrounded by the natural world, they look to make meaning out of that too.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments