A Stranger In My Own Country by Hans Fallada trans. Allen Blunden, book review

An outspoken memoir of life under the Nazis written from a prison cell

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

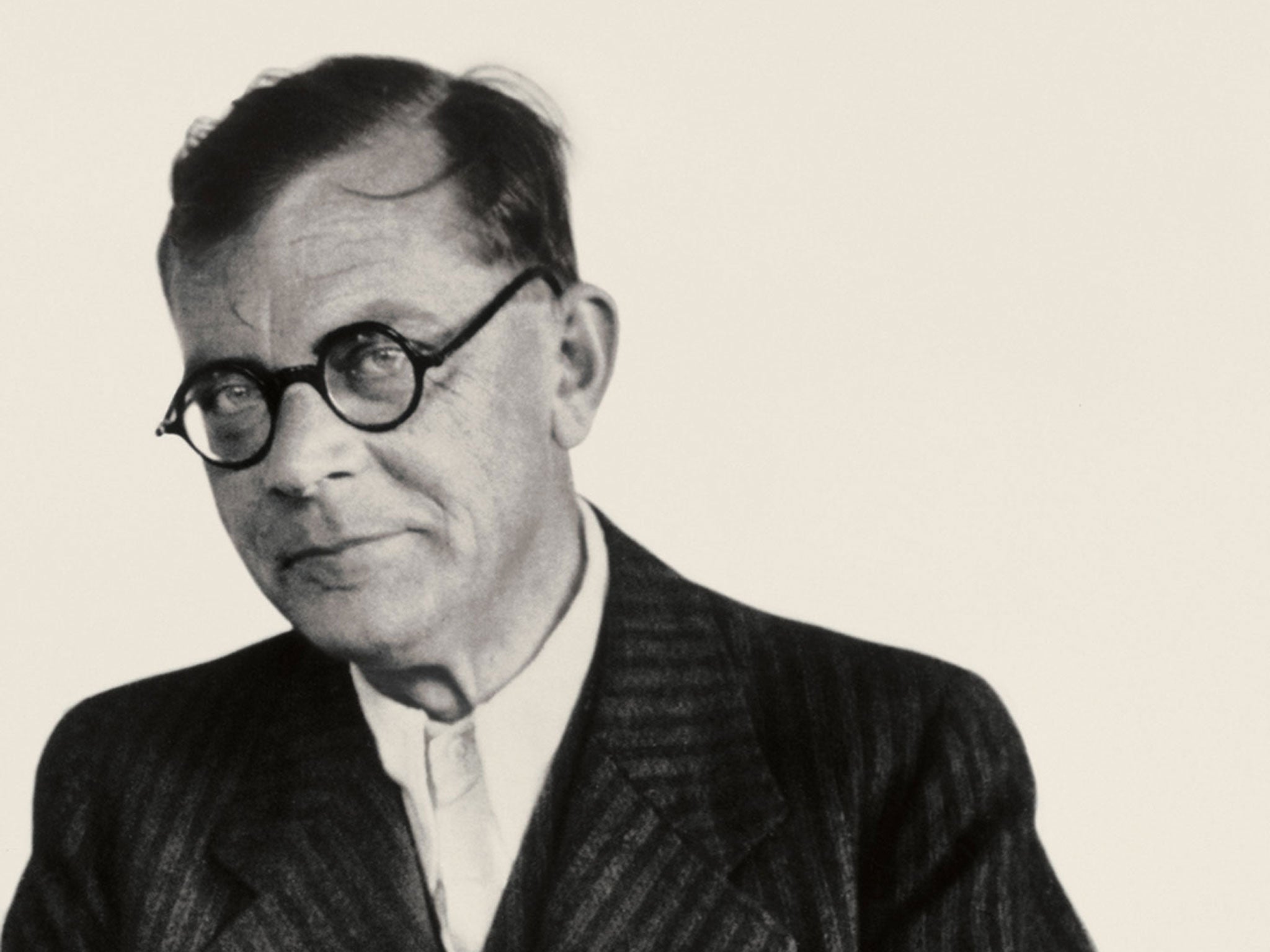

Your support makes all the difference.German writer Hans Fallada had an eventful life, which included killing a friend in a duel-cum-suicide pact at the age of 18, and maintaining a successful writing career over many years despite drug addiction, imprisonment and a fraught relationship with National Socialism. He is most known today for Alone in Berlin, his great novel of the Second World War, completed shortly before his death in 1947, but only recently translated into English.

Since the success of that book, we've had various reprints of novels and stories, and now this. A Stranger in My Own Country carries the innocuous subtitle The 1944 Prison Diary, but in fact stems from perhaps the most extraordinary episode in Fallada's life. In 1944, aged 51, he was arrested and committed to an institution for the criminally insane after drunkenly firing a pistol during an argument with his ex-wife, Anna, with whom he was still living.

Banged up with no hope for release, Fallada went cold turkey and began a peculiar and dangerous writing project "in the shadow of the hangman's noose", as he puts it. Having asked for and received a stack of 92 sheets of paper, he produced a novel about alcoholism (The Drinker, already published) and a couple of short stories, and then embarked on an outspoken memoir about his life under Nazism.

Knowing that discovery would mean death, he wrote in a miniscule, virtually unreadable script, then, when he'd run out of paper, turned the pages upside down and carried on with new lines of writing between the old. Polity Press reproduce facsimiles of some of the pages as the book's endpapers, and they are indeed a thing of compressed, indecipherable beauty.

The memoir covers aspects of Fallada's work and home life before and during the war, including an account of a previous imprisonment when he was shopped to the Nazis' Sturmabteilung (the paramilitary wing) by his landlords – Fallada was never clever about keeping his opinions about the Führer to himself, let alone hushing up his more outspoken friends.

He was only saved from being summarily executed en route to the courthouse by the fact that his doctor happened to be passing the remote spot where his captors had decided to take him out of the car and shoot him. This drama is followed by an equally moving description of his wife Anna's night-time escape from their house to track him down – past an armed guard, and through a thick forest, taking with her their three-year old child, and all while heavily pregnant with twins.

Not all of what follows is so gripping – there is a certain amount of publishing world score-settling, and some tedious description of rural intrigue, but by and large this is the Fallada we recognise from Alone in Berlin: alive to the way that fascism operates by drawing out the worst in people, and to the small battles that ordinary people had to fight just to stay alive. There are anecdotes here that turn up later in the novel, such as the suitcase looked after for an old Communist friend and left forgotten in an attic, that disastrously turns out to contain a printing press, and the strange relationship between the film actor Mathias Wieman and the Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels.

"How am I to communicate anger, bitterness and fear to the reader?" Fallada asks. "He'll be bored stiff reading it! And yet I say to myself: what else could I have written?" It is a fascinating document, but certainly one to place below, not on top of, the novels themselves.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments