A Guide to Berlin by Gail Jones, book review: Heavy-handed take on Nabokov

So long as Jones, a former Booker Prize longlistee, sticks with poignant reflection, the novel is on strong ground

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Walking around Berlin, you might well trip over a Stolperstein or "stumbling stone", metal paving stones commemorating individual victims of the Nazis. Cass, the young Australian protagonist of Gail Jones's sixth novel, on her way to a meeting of fellow expatriate Vladimir Nabokov fans, finds herself transfixed by these Stolpersteine, and their "brassy glow beneath the coating of thin ice".

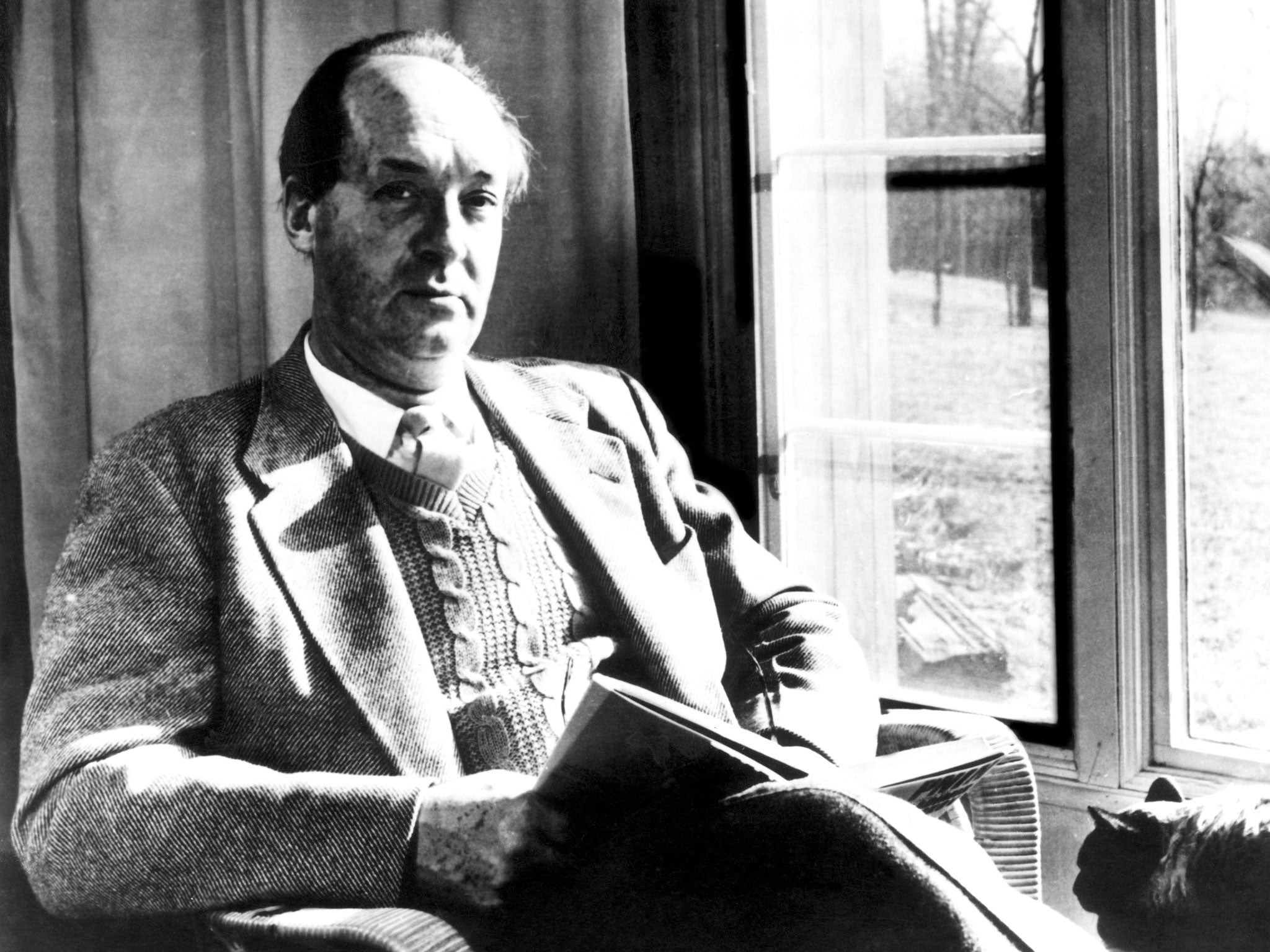

The group of Nabokovians also comprises two Italians, Marco and Gino, American academic, Victor, and a Japanese couple, Yukio and Mitsuko. A Guide to Berlin, which shares its title with a 1925 short story by Nabokov, is as much a guide to the author as the city. And the little group, whose evolving relationships the novel traces, celebrate the ways in which his writing is stippled with its own bright stumbling stones.

When the narrator of Nabokov's "A Guide to Berlin" notes a starfish in the aquarium at Berlin Zoo, a "crimson, five-pointed star", his "regard for the weird vibrancy of things", as Jones puts it, is also a regard for their weird historical resonance. For him, the starfish prefigures the Soviet red star, a symbol of those Bolsheviks who drove the aristocratic Nabokovs out of Russia, their "topical utopias and other inanities that cripple us today". So many of the arresting details lovingly recalled in Nabokov's short stories are, like that starfish, precious memories stored up against the intervening cruelties of time, which also serve to remind us of them.

Just so, Cass's group take turns to share a "speak-memory" – the term taken from the title of Nabokov's autobiography. A "densely remembered" story, personal but often historically aware, whose brilliant details redeem and recall past suffering.

So long as Jones, a former Booker Prize longlistee, sticks with poignant reflection, the novel is on strong ground. Her sensitivity to the vibrancy of things demonstrates a Nabokovian vividness.

A swerve into The Secret History territory, when the group is torn apart by an unconvincingly telegraphed act of violence, places it on thinner ice, coming far too late for a satisfactory resolution, despite much soulful agonising. Jones' point is that certain events are too profound to be "contained within sentences". Something to which Nabokov, a fan of grisly twists himself, adopted a more relaxed approach. Take the freak accident which kills Humbert Humbert's mother in Lolita, glossed by Humbert as, simply, "(picnic, lightning)". It helps to have a sense of humour about these things.

Cass fears "stepping, unbearably heavy upon the names" inscribed on the stolpersteine. The trick might be to tread a little more lightly.

Harvill Secker, £14.99. Order at £12.99 inc. p&p from the Independent Bookshop

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments