Paperback reviews: From Sophia: Princess, Suffragette, Revolutionary by Anita Anand to Gorsky by Vesna Goldsworthy

Also Stone Mattress: Nine Wicked Tales by Margaret Atwood, Adult Onset By Ann-Marie Macdonald and Capitalism: A Ghost Story by Arundhati Roy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

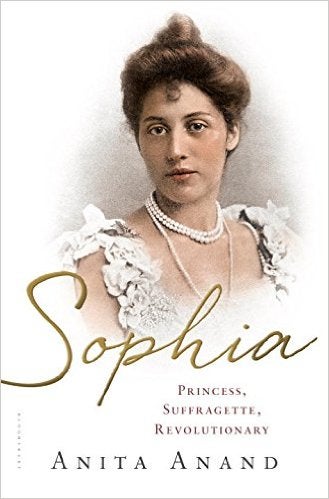

Your support makes all the difference.Sophia: Princess, Suffragette, Revolutionary by Anita Anand - Bloomsbury, £9.99

****

Sophia Singh, daughter of Maharajah Duleep Singh and his wife, Bamba Muller, is a slightly puzzling figure who is difficult to understand: a woman of privilege, born into aristocracy, who became galvanised in later life by political activity on behalf of the powerless. What made this god-daughter of Queen Victoria turn to militant suffrage, for instance?

Anand does an excellent job of providing as full a background as possible to Sophia’s early life, and it is packed with incident and often moments of real hardship and despair. Based in England having lost his legacy in India, her father was a cheat and ran through his money with frightening speed; her mother, too depressed to care properly for her brood of children, died early. Sophia lost her adored brother, Edward, too soon for a child to cope with, one feels, and if it wasn’t for her god-mother stepping in and providing the orphaned family with a grace-and-favour residence, they would probably have been out on the streets.

So perhaps this fall from grace gave Sophia that extra sympathy she needed. Anand shows how visits to India focused her attentions on independence, largely through campaigning for lower caste “untouchables”, but it’s not really clear what gave her her passion for the suffrage campaign. Anand gives us a great deal of background information about the political climate as well as entries from Sophia’s 1906-1907 diaries, which do let us hear her own voice. It is a pity there is less in her own words later on, and her development into a bad-tempered middle-aged lady speaks of some private frustration, some disappointed hope, beyond the delay of women’s suffrage due to the outbreak of the First World War. By the end, Sophia is still a tantalising enigma of a woman.

Gorsky by Vesna Goldsworthy - Vintage, £7.99

****

This updating of The Great Gatsby swaps a money-drenched New York and glamorous Long Island for oligarch-dominated London (specifically Chelsea, or “Chelski”) and Goldsworthy draws parallels with such seeming ease it’s a wonder nobody’s made the connection before now. Her version of Nick, the seemingly detached narrator of F Scott Fitzgerald’s most famous novel, is a rather rootless figure. An outsider, born in Hungary, he has lived in London for many years working mainly in the kind of bookshop you used to find on Charing Cross Road. Gorsky, a handsome and rich Russian oligarch, charges him with the task of creating a first-class library in his beautiful home, a home that happens to be across the road from Russian Natalia, now married to Tom Summerscale (they even have a daughter named Daisy). Nick soon learns that Gorsky is in love with Natalia, a love that has disastrous consequences. Some may ask what is the point of Goldsworthy’s updating, but she places location much more at the heart of her version, accusing London itself of as much culpability in the ruination of individuals.

Capitalism: A Ghost Story by Arundhati Roy - Verso, £7.99

*****

Roy’s greatest strength lies in her ability to make complex political and economic arguments human and clear. The rise of India’s middle-class seems only to be hailed as a good thing by Westerns governments and businesses alike; Roy shows the catastrophic effect of dam-building, forest-clearing, foundation-building on both individuals and political systems alike. Roy acknowledges the good work that foundations often do (which is rather important, as the Lannan Foundation, which is anti-globalisation in its aims and which gives grants to writers and artists, helped publish this book), but she questions their role in public life as well as in the private consciousness of the individuals they support. She also focuses on specific cases of abuse by the state, especially that of Afzal Guru, hanged in secret for his part in a 2001 attack on the Indian parliament. Powerful, passionate and often personal (she records her own hounding by “the mob” over her comments about Kashmir), this work is timely and hugely important in its targets: it’s hard to think of bigger dangers, or more harmful effects, than from faceless, unaccountable conglomerates.

Stone Mattress: Nine Wicked Tales by Margaret Atwood - Virago, £8.99

****

Atwood exploits to the full, without shame and with utter ruthlessness, our secret – or perhaps not so secret – sense of schadenfreude. It’s a sense that might be said to indicate the worst about human beings especially as with these stories, she shows just how easily we fall into its clutches. After all, who can not have sympathy with vulnerable Constance, widowed and alone now, fretting over whether her long-time, much loved husband might have had an affair, that one time in their marriage when he was a bit distant? And who can fail to be delighted that the man who led her a merry dance in her youth, the self-indulgent and over-rated poet, Gavin, ends his life in a bitter marriage, his literary light eclipsed by Constance’s huge commercial success as a fantasy novelist? The theme of literary come-uppance looms large in the collection, appearing again later in “The Dead Hand Loves You”, and it’s revealing how often literary failure or success is linked to personal relationships. Atwood dances wickedly through these lives, skewering pomposity and flashing up lack of self-awareness with a glorious relish.

Adult Onset By Ann-Marie Macdonald - Sceptre, £8.99

***

Macdonald does a brave thing in making the minutiae of daily domestic life the focus of this novel, whilst the “big themes” of life, such as divorce, illness and prejudice, which would normally be in the foreground, are pushed back by the sheer weight of detail. In some ways, it feels almost subversive. But her tale of Mary Rose Mackinnon, who is married to Hilary and who has adopted a more conventional role as a stay-at-home Mum with two small children, walks a wobbly line between the personal and the sheer gossipy. Macdonald is excellent at conversation – the phonecalls between Mary Rose and her mother are superb in their accuracy – but this is a very conversation-dependent novel and the cacophony of voices, whilst perhaps replicating accurately Mary Rose’s environment of noisy, demanding children, partner and family members, can sometimes be wearing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments