‘On the Road’ at 60: How Jack Kerouac’s drug-infused prose became a classic of 20th-century literature

The Beat author’s revered novel – which nearly failed to secure a publisher – turns 60 today. David Barnett looks at its enduring appeal and why it will always have a place in his heart

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I first read On the Road as a 21-year-old, on a long and uncomfortable journey by rattling, toilet-less coach from London to the north of Spain.

I was with a group of friends who always seemed more worldly, more well-read, more savvy than me; they had mentioned Jack Kerouac in passing but other than a reference in a Marillion song the name meant little to me. However, over the course of the previous two years I had begun to drift away from the fantasy and science fiction which had long been my staple. I started to explore wider literary realms, and by 1991 it was the turn of Kerouac and On the Road.

We were on our way to Pamplona. It was July and we were going to take part in the annual San Fermin festival and its week-long party, its morning bull runs through the stockaded cobbled streets. In the footsteps of Ernest Hemingway, of course, who immortalised the spectacle in his novel Fiesta (also known as The Sun Also Rises). But while we followed the trail laid down by the Lost Generation, it was the Beat Generation that was captivating me as I ignored the scenery outside the coach window and instead became immersed in Kerouac’s world.

Perhaps it’s surprising that I didn’t discover Kerouac until I was 21. But I had eschewed university in favour of starting work as a journalist at the age of 19, so missed out on those student years and their de rigeur texts; instead I discovered such things piecemeal and haphazardly. Perhaps if I had taken up a degree course in literature, I might have had a better understanding of what I was reading on that coach trip. But I didn’t have the toolkit of literary criticism to fully comprehend what On the Road actually was; was it fiction? Was it non-fiction disguised as fiction? I had no idea what a roman a clef was back then; if you’d have asked me I might have hazarded a guess that it was something to do with musical notation, rather than it being a perfect descriptor of Jack Kerouac’s writing: real people, real events, given the gloss and sheen of fictional presentation.

All I really knew was that On the Road absorbed me completely. It was like nothing I’d read before. It didn’t follow any traditional structure of fiction that I’d encountered previously. The language was lyrical and urgent and demanded to be read out loud, under my breath, to appreciate the rhythm. It was poetry and prose all mixed together that bounced along to a head-nodding, foot-tapping cadence.

My copy of On the Road was a Penguin 20th Century Classics edition, with a pale-blue spine. On the front cover was a photograph by Robert Frank, entitled “Teardrops”. It depicted a table in an American diner with its jukebox selector, and the ghost of a wide American car in the background. Somewhat surprisingly, it survived the trip to Pamplona in remarkably good shape; I still have it today.

On the Road is the Jack Kerouac novel everyone has heard of, but it’s only one part of Kerouac’s great literary endeavour; a vast, Proustian tapestry of his life and the others that weave in and out of it. There’s The Dharma Bums,The Subterraneans, Visions of Cody, Doctor Sax… 13 novels in all, which I tracked down and devoured, slowly realising that the recurring characters under fictional names were all real people in what Kerouac dubbed The Duluoz Legend – Duluoz being one of the alter egos he created for himself at the behest of his publishers who feared these tales of drugs, booze and debauchery might bring legal problems on their heads if Kerouac used real names.

Still, is is On the Road that is the pivotal book in the whole series. It is, in a way, Kerouac’s “A New Hope”... just like the seminal film Star Wars began halfway through the sequence, it’s the one beloved of most. On the Road details the fast-living years of Kerouac’s life, and was the first novel in the Duluoz Legend published (not counting his debut, The Town and the City, which is a fine novel and a homage to Kerouac’s literary hero Thomas Wolfe, but pure fiction nevertheless).

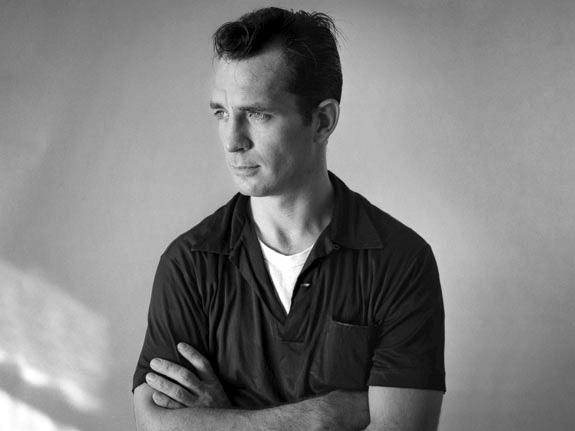

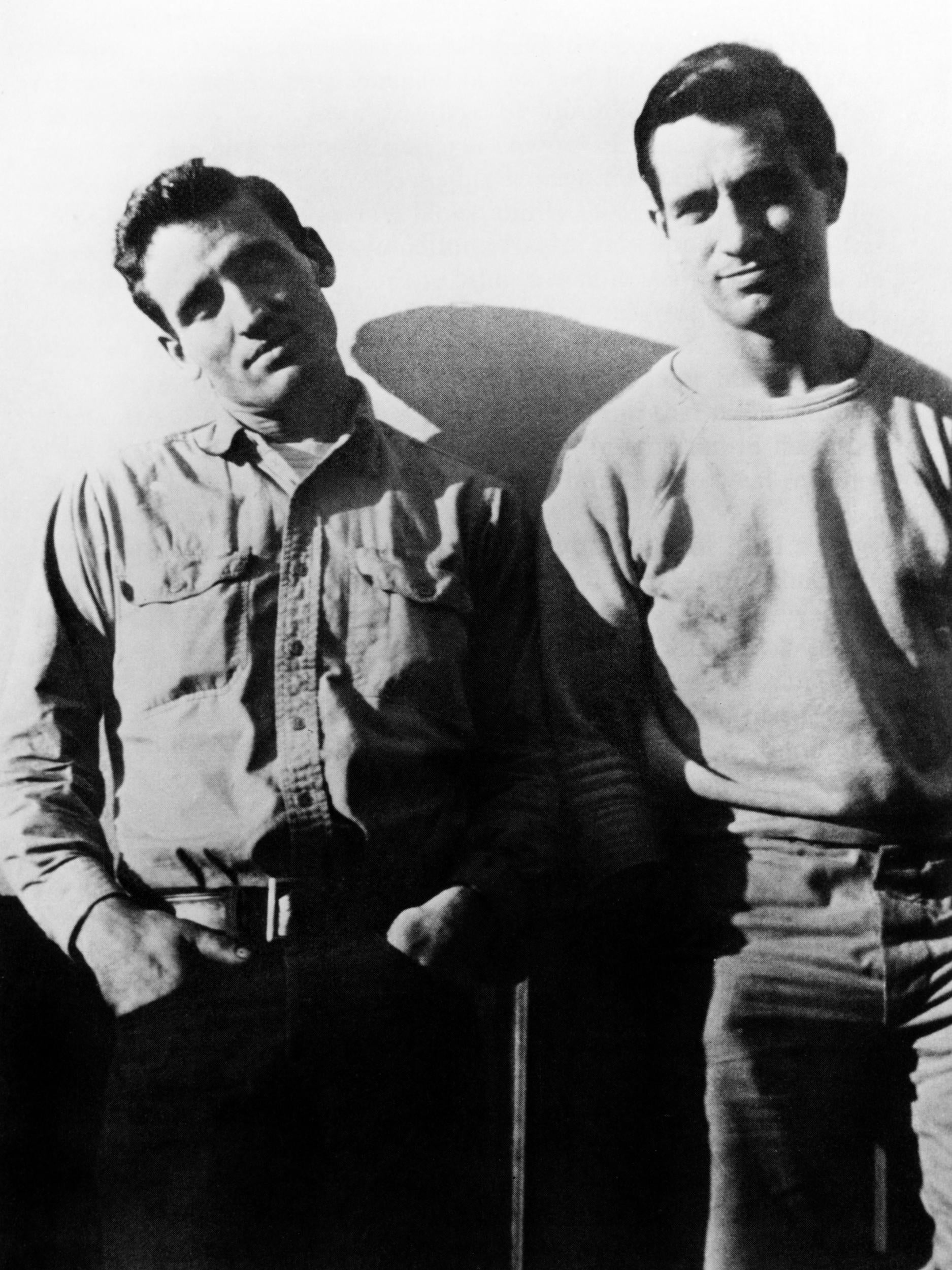

And it was published 60 years ago today, 5 September 1957. But the journey to being published was long. The bulk of the novel covers events that took place between 1947 and 1950, when Kerouac, after dropping out of college and embarking on a short career as a merchant seaman, landed in New York and got in with the counter-cultural crowd he would christen the Beat Generation. People like poet Allen Ginsberg, writer William S Burroughs, and the man who would become a sort of muse for Kerouac, Neal Cassady. Cassady was a slum kid who’d led a life of petty crime, but had ambitions to be a writer. Kerouac imbued him with an almost mystical presence, painting him as the great American frontiersman, a dust-covered hobo-cowboy navigating the brave new world of post-war America. Together they travelled from New York to Mexico, and that is essentially the meat of On the Road, with Cassady recast as the free-spirited Dean Moriarty in the book.

Kerouac famously completed the first draft of the book in 1951, after three weeks of drug-fuelled writing on one continuous scroll of taped-together sheets of paper – 120ft long, as legend has it, no paragraph breaks, just one mesmerising screed of typewritten spontaneous prose. It’s a wonder it ever got published at all, but Kerouac had a champion at the New York publishing house Viking in the shape of Malcolm Crowley, who spotted the potential in Kerouac’s unorthodox manuscript and fought for it in-house. It took many revisions and several years, but On the Road was finally published in 1957, when Kerouac was 35.

Over the next decade he continued to write, expanding his Duluoz Legend, sometimes concentrating on his childhood in Massachusetts, other times leaping ahead to the Beat and post-Beat years. Like Kerouac’s famous roman candles analogy from On the Road (“The only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars and in the middle you see the blue centerlight pop and everybody goes ‘Awww!’”) the Beat Generation flared brightly but for a short time, and in the Sixties were supplanted by the hippies and several other burgeoning youth movements. The Beats had ushered in the age of the counter-culture and paved the way for young people to stand up and say for the first time that they were not simply going to follow the paths laid down by their parents, but like every supplanted generation, Kerouac didn’t understand and had little truck with the hippies.

He died, from internal bleeding brought on by years of alcohol abuse, in October 1969, living with his third wife and his mother, in St Petersburg, Florida. This was 82 days before I was born. Kerouac was 47 when he died, the same age that I am now. Why do I point this out? I make no analogy between my life and Kerouac’s. I’m simply often surprised that the life of this chronicler of a world that seems lost to history, so very nearly overlapped with mine. And yet, in a way, it did; ever since I was 21, I’ve felt that Kerouac has been a part of my life.

My old copy of On the Road is by my side as I write this. About three years after that trip to Spain, I found myself in Boston, and struck out for Kerouac’s home town of Lowell. It was a baking hot day in July, and as I stepped off the train, alone in this pretty red-brick town, in my early 20s, I don’t think I’d ever felt so far away from home.

I walked in the searing heat to Edson Cemetery, much further out of town than it seemed on the hand-drawn map they’d given me in the tiny tourism office, and I stopped for a Coke in a Dairy Queen, which felt simultaneously familiar from years of American literature and movies, yet unbearably exotic.

Kerouac’s headstone is flat, laid into the earth. It says on it “Ti Jean”, or Little Jack in the French-Canadian of his family. A childhood nickname. Exhausted, I sat on the parched earth next to the headstone, festooned with empty beer bottles and a joint. After his death, and a lifetime of wandering, Kerouac had come home.

Jack Kerouac has been dead now for longer than he was alive, and his most famous novel remains a divisive book. There are those, like me, who love it. For as many people, the rhythmic, directionless prose is off-putting (Truman Capote infamously dismissed Kerouac’s work as, “That’s not writing, that’s typing”). But I don’t think it can be denied that On the Road, and Jack Kerouac, have earned their place in the literary firmament.

Where he burns like a fabulous roman candle, and never did say a commonplace thing. On the Road is 60 today; let’s watch it, still exploding like spiders across the stars. Everybody say “Awww.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments