Notting Hill Editions essay competition: In My Head I Carry My Own Zoo

Karen Holmberg writes on the art of John Digby’s collages, which fuses the grotesque and the delicate inside the shape of an animal, which, as she says, preserves the world by putting pieces together

Karen Holmberg is an associate professor teaching in the MFA Programme at Oregon State University. Her primary genre is poetry but she has written and published in many literary magazines including New England Review, Indiana Review and Black Warrior Review. Her most recent poetry collection, Axis Mundi, won the 2012 John Ciardi Prize for Poetry.

In My Head I Carry a Zoo

A petition appears in my inbox without salutation, preamble, or signature:

END CRUELTY TO MOTHS!

Each year millions of moths are painfully deprived of their testicles for the making of MOTH BALLS...

I recall the moment weeks before in John Digby’s studio when I’d asked why I had found so many collages in the shape of butterflies, but none in the shape of moths.

My twelve-year-old daughter dissolves in helpless hilarity when I read the message aloud to her; she begs to hear it again and again. It’s a silly joke, of course. But there’s something serious to it as well. Tomfoolery fuels the engine of Digby’s artistic imagination; puns, literalising, and other forms of harmless absurdity create the spark of astonishment and surprise necessary to transform our perception of the world – and decenter us from its midst. Like Gerard Manley Hopkins, who defined the human being as “Jack, joke, poor potsherd, patch, matchwood, immortal diamond”, Digby would describe the human being as (at best) a breathing motley of the silly and refined, the perishable and the permanent.

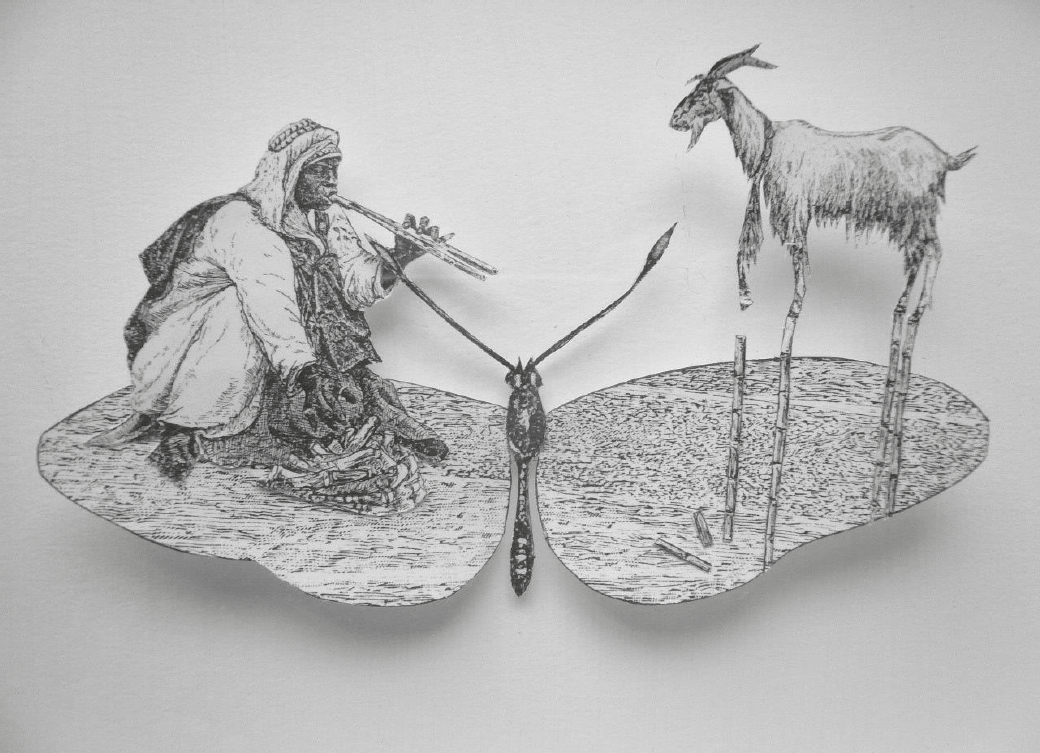

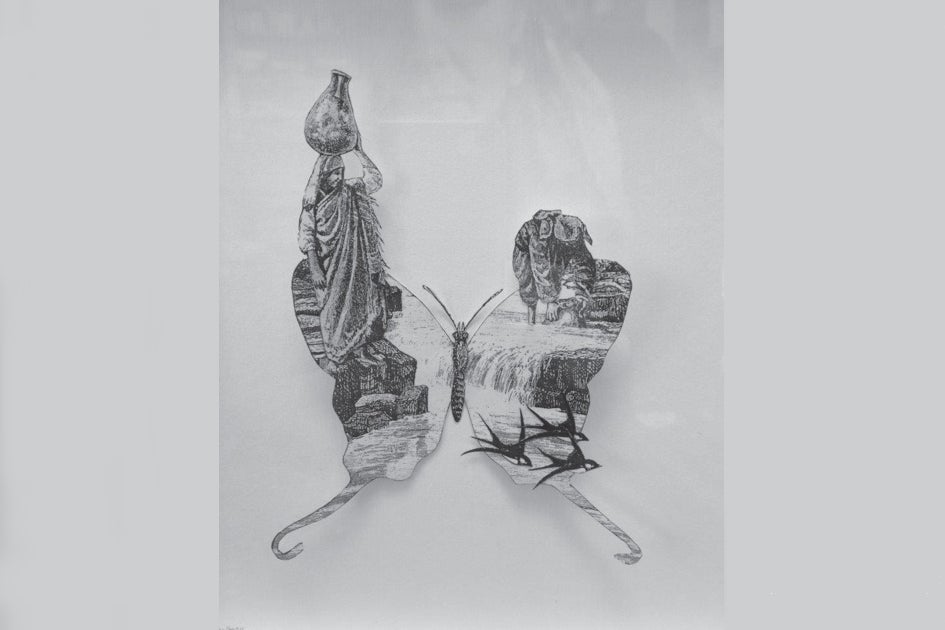

His art reflects this variousness. The collages, made from engraved illustrations found in damaged 19th century books, preserve what is essentially fragile, using archival practices to arrest deterioration. His art extends the life of these fragments by tugging them back into the modern moment and re-illuminating their beauty. Often, his art fuses the seemingly incompatible – the grotesque and the delicate, the violent and the peaceable, the whimsical and the serious, the earthy and the ethereal – yet he always achieves a luminous integrity. He embeds yoked oxen like organs within a fish’s abdomen; a Berber flute player crouches in the dust opposite a goat who perches atop towers of sticks, the figures perfectly balanced in the scale of a butterfly’s wings. Somehow, these figures speak to each other, belong to each other, though they may well have been transplanted from entirely different books. When I asked him about his foam core sculptures (antennal contraptions gathering dust on top of a bookshelf, inspired by a local cable program on aliens “listening in”) or the collage poems he writes (drawing the language from a select group of books he’s kept on his drafting table for years) he chuckles at himself – it’s all jokes, you see – but this doesn’t cancel out their beauty or their seriousness. Somehow Digby interfuses radically different qualities into his art to generate a miraculous levity, an insistent thisness.

Paradox defines the process itself. The animal collages – usually only a few inches square – magnify by miniaturising. The shape of the animal (fish, bird, camel and, most frequently, the butterfly) becomes the stage on which the human drama plays out, or the field of vision in which a rugged landscape reposes. Digby begins the collage by reproducing the engraving of the animal on acid-free paper. Following the animal’s outline precisely with a scalpel, he removes the animal shape to create a negative space through which a second scene, most often a landscape with human figures, can be viewed. Once he’s selected the view that is the most arresting response to the animal’s habits, spirit and form, he adheres the two pieces, and then follows the animal’s inner outline with his scalpel, freeing it from the paper. The moment the animal shape is lifted out, he accomplishes a vertiginous magic. Two things of vastly different scale have been melded together to become a simultaneous whole. We can never see just the held landscape, or just the animal form. Our imagination becomes bifocal, pouring back and forth between these two poles continuously.

Framed inside the figure of a fish, a giant squid erupts between two small sailboats as the sailors gaze on in sublime agony. Inside the borders of a butterfly, St Sebastian with wrists and ankles bound, sinks into a swoon, pierced by a Native American warrior’s arrows. As we contemplate the scene, we forget and recall repeatedly that the mythic drama is playing out in the minute arena of a fish or a butterfly, the way we can forget and recall, when watching a play, that the stage contracts and simulates a world.

Because Digby’s animal collages often enclose human industry or a vast, craggy landscape, they suggest that even the smallest, most fragile creature constitutes an enormity. Miniaturised within the animal frame, the human figures become enigmatic emblems of our essential condition, like the scenes depicted on Keats’s Grecian urn. In fact, a Digby collage works in a similar way to Keats’s ode, offering up a world of self-sufficiency, a world that makes us aware of its indifference and our invisibility. I peer into this world like its God, yet at the same time, I am dwarfed and humbled by it.

***

I was considered uneducable. I could read, but not write; I was dyslexic and couldn’t spell. I had a terrible stutter. My schoolmasters beat me, thinking I was playing the fool, or else only called on me at roll, and otherwise ignored me as an idiot. But I adored books. Long before I even started school, my grandfather had bought me an illustrated book of the English birds, and I fell in love with the pictures. He taught me to read all the descriptions of the birds, their nests, their eggs, and their haunts.

Later, I came to love books as a visual medium. When I looked at the page, I saw the black ink on the white page as very beautiful in itself, aside from the meaning. I see the various tones of black and white pages, and the subtle grays of my papers as verbs, nouns, and adjectives; when I build a collage, I compose as the poet would when writing a poem. I have, over the years, come to see my collages as visual poems.

*Poesis: Two Fish with Wading Women, Rowboat, and Boy

I’m seeing a wordless poem. Not seeing, exactly. Some intermediary act between reading and seeing is required. On one hand the mood is grasped instantaneously; and yet the eye is compelled to rove the details, to ricochet between figure and frame in order to knit together a narrative. Here the frame is compound: two fish form larger and smaller islands upon which the human figures enact a blissful idleness. In the larger scene, a young woman tows a boat through the shallows, one hand gathering up her skirt; on the edge of the boat, a woman perches, dangling her legs; a boy poles astern. Balance, symmetry, as if we watch a dance: the woman at the bow looks over her shoulder at the woman on the smaller fish in the foreground, who also gathers her skirts in one hand, who turns her head as if she’s heard her name. Many of Digby’s collages rhyme in their textures; here, the striated fins of the fish echo the women’s pleated garments, as well as the ribs and planks of the rowboat. As I gaze at this collage, I am like a person at a magic show who knows how the trick is done, but forgets to watch at the crucial moment; like magic, art is the successful illusion of unity created by a genius of arrangement. Perhaps all art triggers magical thinking, the vestige of childhood ‘pretend’. Pretend these women are sisters, the boy their younger brother; pretend they’ve gone to the sea on holiday, have rented boats, are absorbed in the pleasure of making the boats go wherever they will. The image touches some internal wellspring of earliest memory, releasing a limpid day that seemed to go on forever because nothing had to happen. You don’t want to hear the women are taken from three different engravings in three different books. It would be like hearing the radiant day above Tintern Abbey never existed, or that Wordsworth had invented his sister. But maybe, in the end, it wouldn’t matter. A poem is a world we believe in, even as we know we can’t.

***

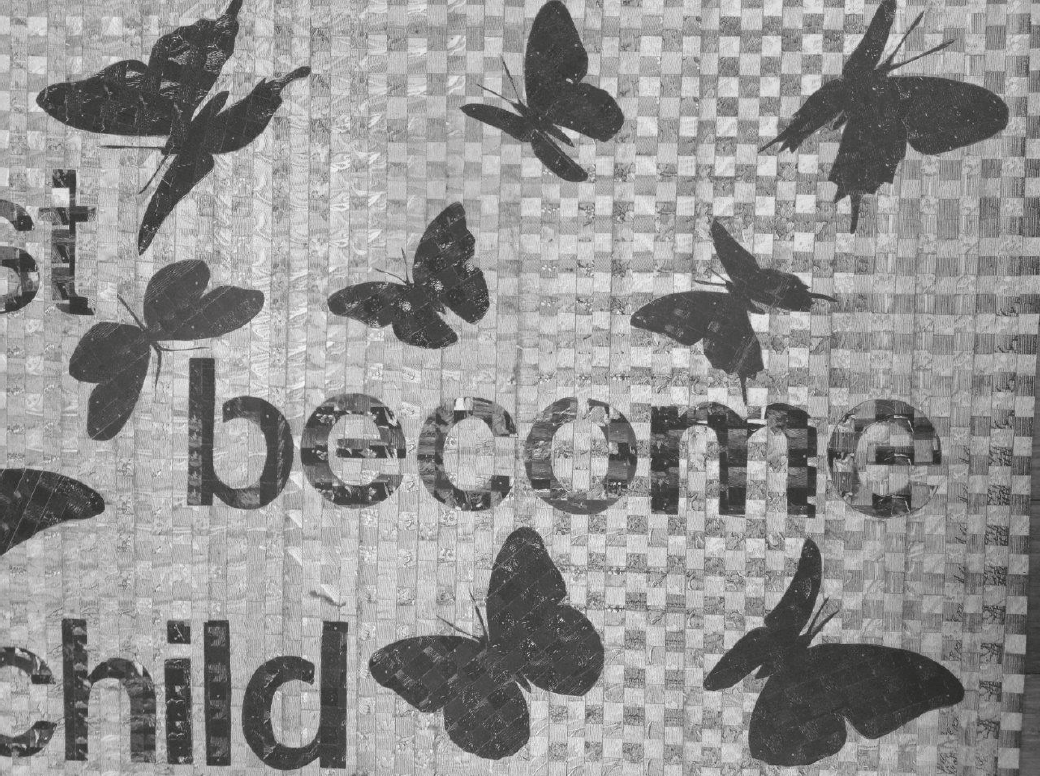

We live in an unprecedented era of fragmentation, explosion and ruin. What marks the era is the spray of the mass shooter’s bullets, the targeted bombing of world heritage sites, the snow-like drift of documents and ashes from the collapsing Towers, the beheading of those, like journalists, who attempt to record the present, to preserve our record…. When I look at John Digby’s animal collages, I’m witness to the quiet work of an imagination that holds sacred the thisness of each being, and wishes to preserve a space for its call to us, and our response to it. In doing so, artists like Digby refuse to consign the world to diminishment and obliteration.

The world exists to do collage, to put pieces together – all types – to save it and understand it, preserve it as a holy place. Collage creates another world which can be read and understood like the inner life, the spirit of the thing. It looks through the opacity of matter into the spiritual heart of place.

Extract from ‘Five Ways of Being a Painting and other essays’ published by Notting Hill Editions, £14.99. Quote INDY17 to buy the book at the special price of £12.00 from nottinghilleditions.com. Tomorrow: The Future Is Nostalgia by Patrick McGuiness

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments