Researcher discovers unknown history behind the Voynich manuscript, the world’s most mysterious text

For centuries, the origins and purpose of the Voynich manuscript has confounded academics and researchers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A researcher has made new claims about the historical journey of a centuries-old manuscript, widely considered one of the world’s most mysterious.

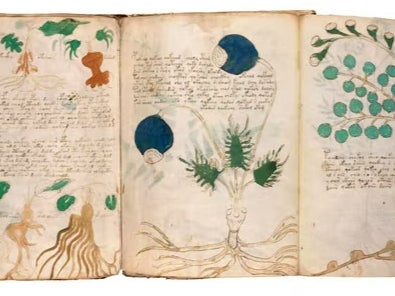

The Voynich manuscript is significant for having a unique, indecipherable script and colourful illustrations. Its authorship and purpose has been long debated.

Through carbon dating, researchers of the parchment has placed its origin in the 15th century. Scholars have traced its earliest ownership back to the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, who bought it for 600 “ducats”, or gold coins, sometime between 1576 and 1612.

Before now, its ownership in the years before being bought by Rudolf II have remained unknown.

Yet, through investigation by Stefan Guzy of the University of the Arts Bremen, Germany, there are some possible answers as to the owner of the Voynich manuscript in its 100-odd years after its creation.

Guzy embarked upon a deep study of imperial account journals kept by Rudolf’s court to figure out who could have sold the Voynich manuscript to the emperor.

“My idea was to compile all book-related transactions by analysing the imperial account books of the Hofkammer (Imperial Chamber) in Vienna and Prague, where all ingoing and outgoing letters were registered,” Guzy writes in his research paper, according to The Art Newspaper.

“If there was any transaction involving 600 gold coins, then the chance was pretty high that this acquisition was the one mentioned in the Marci letter.”

He discovered only one receipt that described a sale of 500 silver thaler – the equivalent of 600 gold coins – which was a purchase of a collection of manuscripts from the physician Carl Widemann in 1599.

Since 600 gold coins would have been an expensive price for a singular manuscript, then the idea that the Voynich would have been a part of a larger collection makes sense.

Furthermore, Guzy’s research suggests a possible owner of the manuscript before Widemann – the botanist Dr Leonard Rauwolf, in whose Augsburg house Widemann lived.

The researcher discovered that Rauwolf owned a small collection of books, which makes it more likely that Widemann would have acquired the Voynich from him.

Guzy writes: “The Voynich Manuscript could be one of the books Widemann got his hands on and sold to the emperor, because, for sure, it would have already looked valuable back then to a collector of weird and precious things like emperor Rudolf.”

In 2019, Dr Gerard Cheshire, a linguistics research associate at the University of Bristol, claimed to have cracked the manuscript’s code in just a fortnight – despite academics such as Alan Turing and institutions such as the FBI never succeeding in the mission.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments