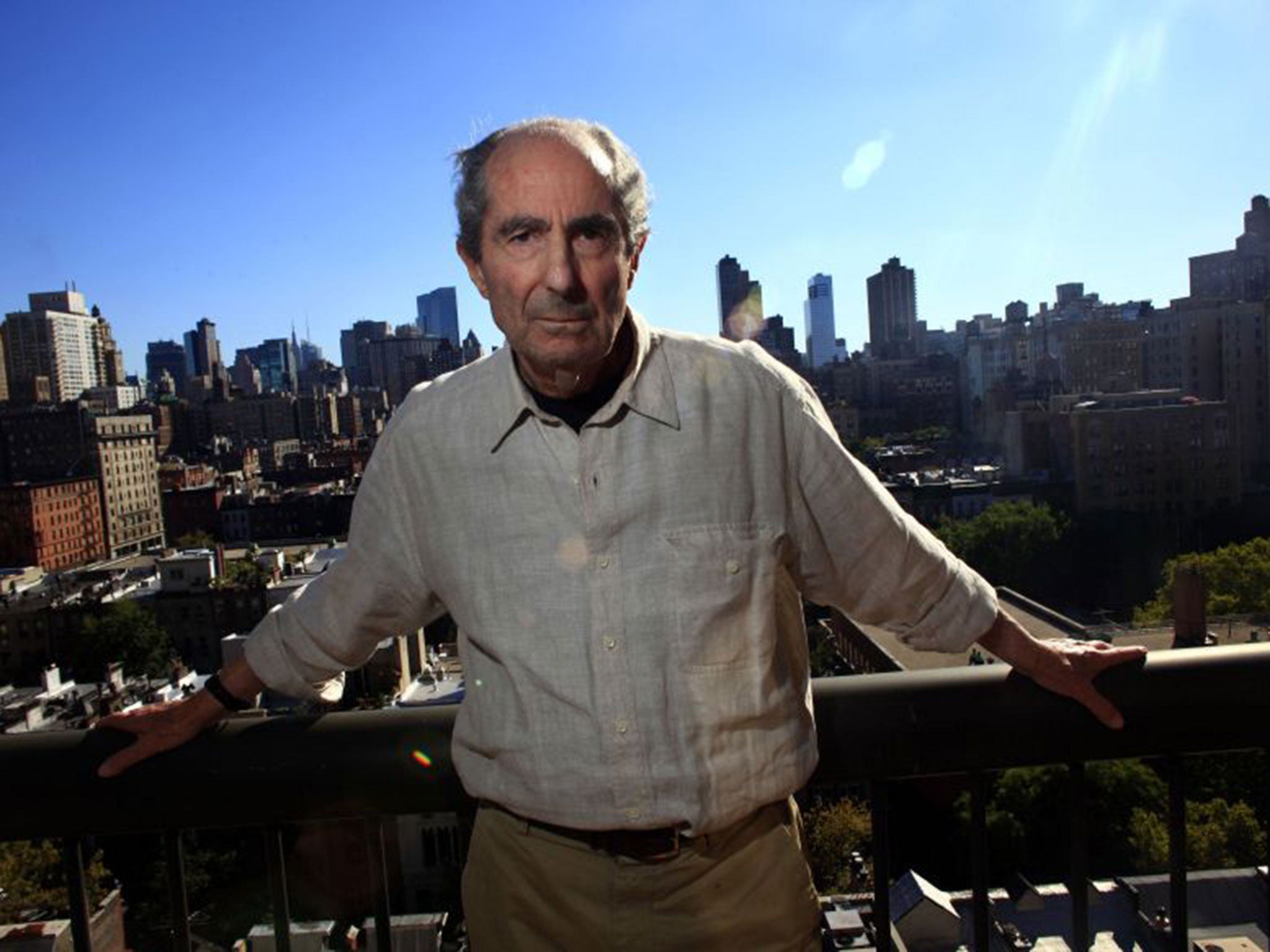

Philip Roth dead: Award-winning satirist and 'American Pastoral' author dies aged 85

Author of more than 25 books, Roth was an uncompromising realist

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The trailblazing satirist and award-winning author Philip Roth, known for his explorations of masculinity and middle-class Jewish American life, has died at the age of 85.

Andrew Wylie, Roth’s literary agent, confirmed he died in a New York City hospital of congestive heart failure.

Roth was a fearless narrator of sex, death, assimilation and fate, from the comic madness of Portnoy’s Complaint to the elegiac lyricism of American Pastoral.

Author of more than 25 books, Roth was an also uncompromising realist, confronting readers in a bold, direct style that scorned false sentiment. He once described himself as having “a resistance to plaintive metaphor and poeticised analogy”.

He was an atheist who swore allegiance to earthly imagination, whether devising pornographic functions for raw liver or indulging romantic fantasies about Anne Frank.

In The Plot Against America, published in 2004 (and soon to be adapted by The Wire creator David Simon), he placed his own family under the antisemitic reign of President Charles Lindbergh. In 2010’s Nemesis he subjected his native New Jersey to a polio epidemic.

Roth was among the greatest writers never to win the Nobel Prize (there were calls for him to be decorated with it right up to his death), but he received virtually every other literary honour, including two National Book Awards, two National Book Critics Circle prizes and, in 1998, the Pulitzer for American Pastoral.

He was in his twenties when he won his first award, impressing critics and fellow writers by producing some of his most acclaimed novels in his sixties and seventies, including The Human Stain and Sabbath’s Theater, a savage narrative of lust and mortality he considered his finest work.

He identified himself as an American writer, not a Jewish one – seeing the latter classification as limiting – but for Roth the American experience and the Jewish experience were often the same.

While predecessors such as Saul Bellow and Bernard Malamud wrote of the Jews’ painful adjustment from immigrant life, Roth’s characters represented the next generation. Their first language was English, and they spoke without accents. They observed no rituals and belonged to no synagogues.

The American dream, or nightmare, was to become “a Jew without Jews, without Judaism, without Zionism, without Jewishness”. The reality, more often, was to be regarded as a Jew among gentiles and a gentile among Jews.

In the novel The Ghost Writer he quoted one of his heroes, Franz Kafka: “We should only read those books that bite and sting us.”

For his critics, his books were to be repelled like a swarm of bees.

Feminists, Jews and one ex-wife attacked him in print, and sometimes in person.

Women in his books were at times little more than objects of desire and rage and The Village Voice once put his picture on its cover, condemning him as a misogynist.

A panel moderator berated him for his comic portrayals of Jews, asking Roth if he would have written the same books in Nazi Germany.

The Jewish scholar Gershom Scholem called Portnoy’s Complaint the “book for which all antisemites have been praying”.

When Roth won the Man Booker International Prize, in 2011, a judge resigned, alleging that the author suffered from terminal solipsism and went “on and on and on about the same subject in almost every single book”.

In Sabbath’s Theater, Roth imagines the inscription for his title character’s headstone: “Sodomist, Abuser of Women, Destroyer of Morals.”

Ex-wife Claire Bloom wrote a best-selling memoir, Leaving A Doll’s House, in which the actress remembered reading the manuscript of his novel Deception.

With horror, she discovered his characters included a boring middle-aged wife named Claire, married to an adulterous writer named Philip.

Bloom also described her ex-husband as cold, manipulative and unstable. (Although, alas, she still loved him). The book was published by Virago Press, whose founder, Carmen Callil, was the same judge who quit years later from the Booker committee.

Roth’s wars also originated from within.

He survived a burst appendix in the late 1960s and near-suicidal depression in 1987. After the disappointing reaction to his 1993 novel, Operation Shylock, he fell again into severe depression and for years rarely communicated with the media.

For all the humour in his work – and, friends would say, in private life – jacket photos usually highlighted the author’s tense, dark-eyed glare.

In 2012, he announced that he had stopped writing fiction and would instead dedicate himself to helping biographer Blake Bailey complete his life story. By 2015, he had retired from public life altogether.

He never promised to be his readers’ friend; writing was its own reward, the narration of “life, in all its shameless impurity”.

Until his abrupt retirement, Roth was a dedicated, prolific author who often published a book a year and was generous to writers from other countries.

For years, he edited the Writers from the Other Europe series, in which authors from Eastern Europe received exposure to American readers; Milan Kundera was among the beneficiaries. Roth also helped bring a wider readership to the acclaimed Israeli writer Aharon Appelfeld.

Roth began his career in rebellion against the conformity of the 1950s and ended it in defence of the security of the 1940s; he was never warmer than when writing about his childhood, or more sorrowful, and enraged, than when narrating the shock of innocence lost.

Additional reporting by AP

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments