National Poetry Day 2018: Independent writers’ favourite poems from William Blake and Robert Burns to WB Yeats

Our selection of great verse from the 17th century to the age of Instagram

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.National Poetry Day 2018 takes place on Thursday 4 October.

Conceived by William Sieghart of the Forward Arts Foundation in 1994, the occasion celebrates the medium and seeks to widen its audience, each year organising public events across the country grouped around a loose literary theme, 2018’s being “change”.

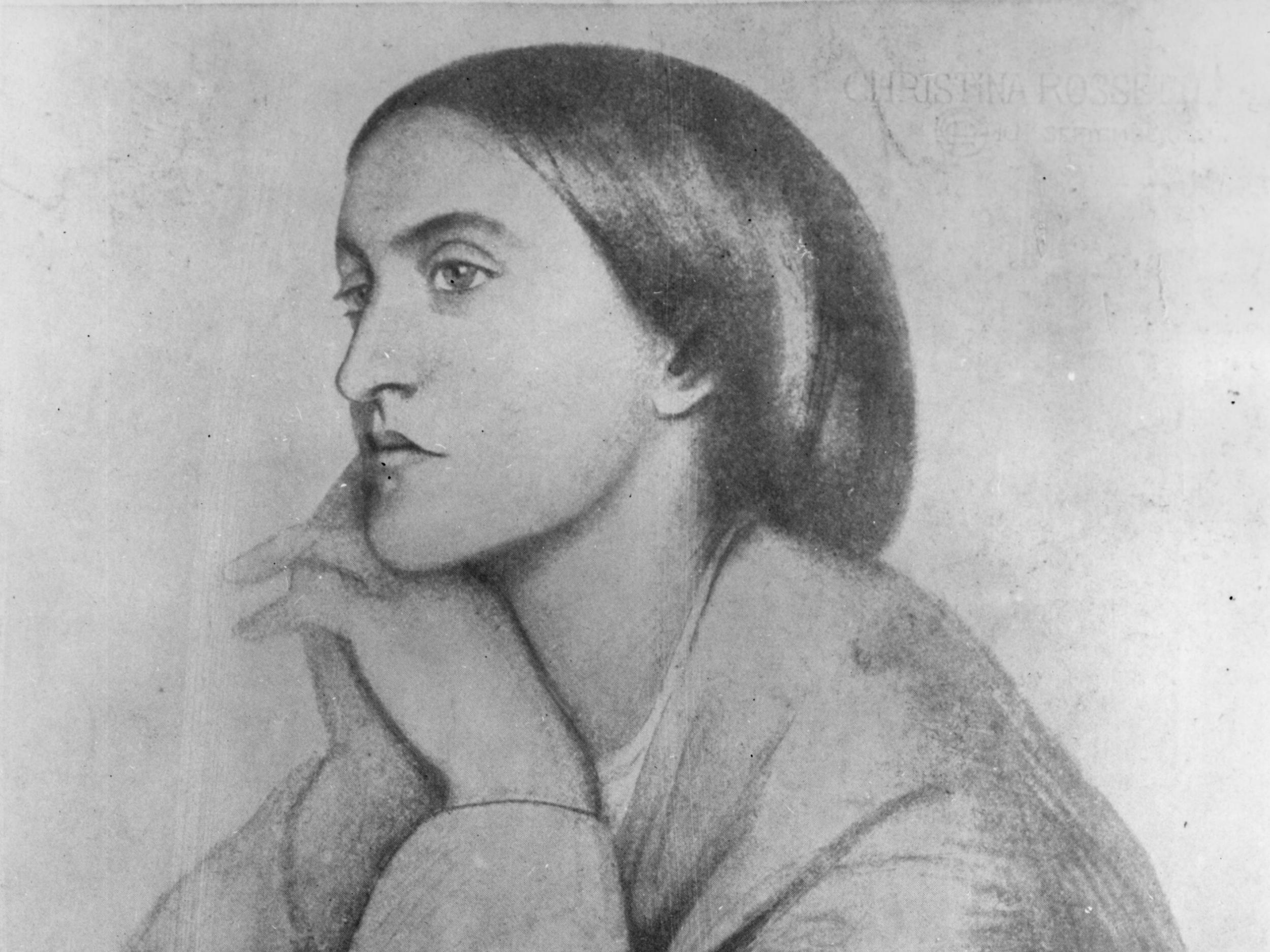

Among the foundation’s choices taking inspiration from ideas of transformation and transition are “Dear March – Come In” by Emily Dickinson, “The Seedling” by Paul Laurence Dunbar, “Child’s Song in Spring” by E Nesbit and “Caterpillar” by Christina Rossetti, all of which you can read in full on its website.

In the spirit of the day, here are some favourite poems from The Independent’s contributors.

Seaside Golf (1953) by John Betjeman

“How straight it flew, how long it flew,

“It clear’d the rutty track

“And soaring, disappeared from view

“Beyond the bunker’s back –

“A glorious, sailing, bounding drive

“That made me glad I was alive.”

I’m a golf addict and I find it almost impossible to describe to non-believers the unrivalled joy golf can provide. This poem does just that – it illustrates the game of golf at its sweetest.

This was allegedly inspired by a birdie the poet secured on the 13th hole of his beloved Cornish golf course, St Enodoc. Having played this course, you can imagined the ecstasy of hitting three perfect shots on a tough par 4 next to a sea estuary with your nostrils full of salty air and seaweed.

Putting the golf to one side, like many of his poems, it is a celebration of England and its treasures, man-made and natural.

Matt Payton

A Poison Tree (1794) by William Blake

“I was angry with my friend;

“I told my wrath, my wrath did end.

“I was angry with my foe:

“I told it not, my wrath did grow.”

It’s basically about how relationships and interactions can deteriorate if you bottle things up and don’t express your true feelings, leading to resentment. I think it’s very powerfully written.

The way it shines a light on how you are personally in control of your own anger and feelings, you just need to talk and be open. That’s my interpretation at least!

Jack Webb

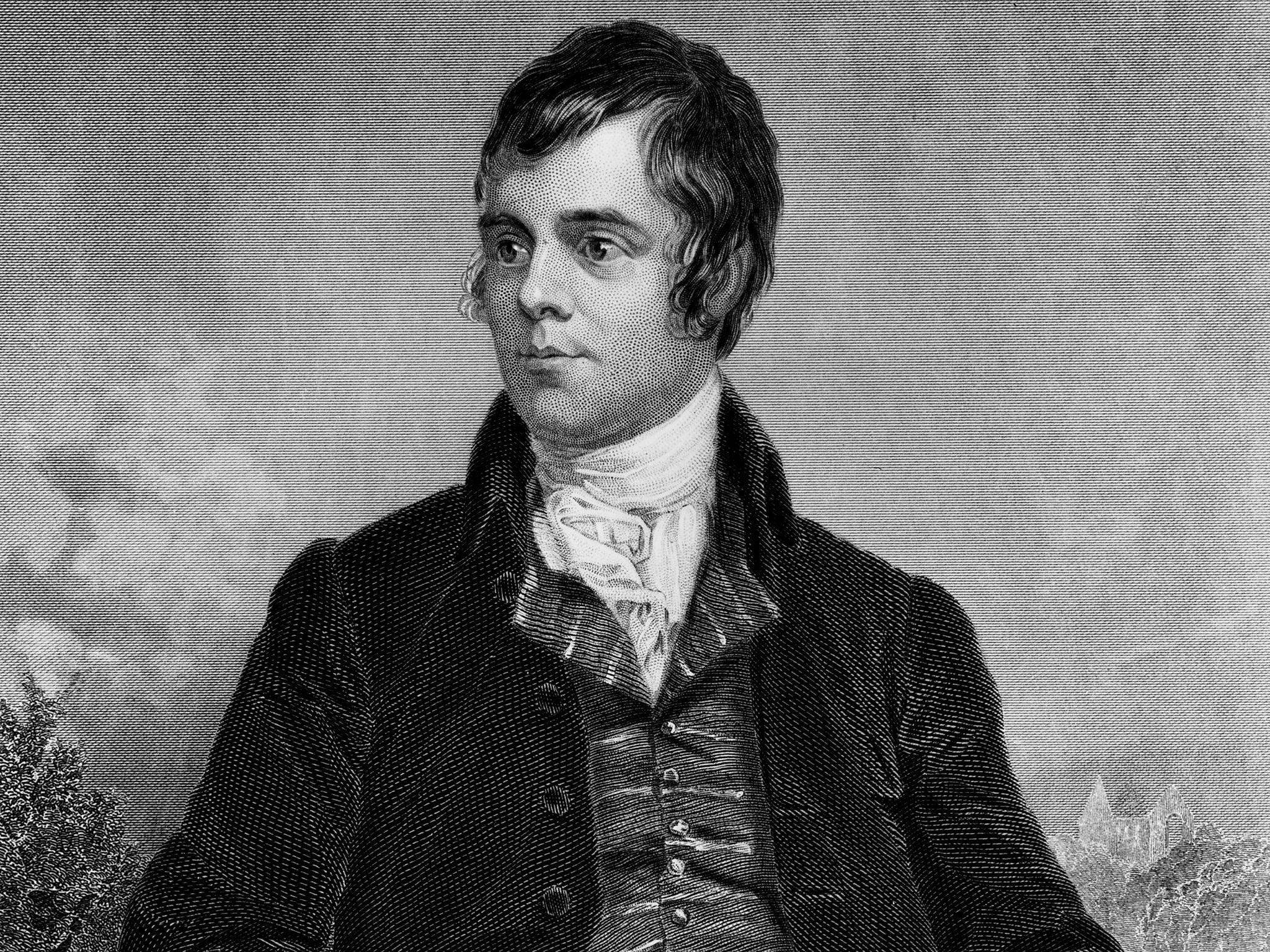

Ae Fond Kiss (1791) by Robert Burns

“Had we never lov’d sae kindly,

“Had we never lov’d sae blindly,

“Never met-or never parted,

“We had ne’er been broken-hearted.”

In “Ae Fond Kiss”, Burns’ story of unrequited love, I think the above lines are a reminder that the beautiful thing about love is often its fragility.

Jo Turner

Kale (2016) by Charly Cox

Charly Cox’s new book, She Must Be Mad, has redefined poetry for my generation.

She captures the struggles and joys of millennial life in a perfect mix of quirky and poignant writing, as evidenced by one of my personal favourites “Kale”.

Sirena Bergman

Requiem for the Croppies (1966) by Seamus Heaney

“Terraced thousands died, shaking scythes at cannon.

“The hillside blushed, soaked in our broken wave.

“They buried us without shroud or coffin

“And in August... the barley grew up out of our grave.”

In this poem, Seamus Heaney describes the 1798 Battle of Vinegar Hill, in which Irish rebels were brutally cut down as they fought for their independence from Britain.

A narrative flows through Irish mythology and literature that the country’s patriotic martyrs are buried in the soil, only to spring back up and be reborn in the next generation of rebels. Suitably, this poem was written for the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising – another failed uprising, but one that inevitably sparked the final push for independence.

When Heaney won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1995 it was for his evocation of “the living past” and while that theme threads through dozens of his poems, it is always this one that I feel best exemplifies it. For better or for worse in Ireland, our past hangs around; haunting the glorious landscape, never too far beneath the surface.

Ben Kelly

End of Hypnosis (2007) by Tite Kubo

“Those who do not know what love is liken it to beauty.

“Those who claim to know what love is liken it to ugliness.”

I present to you the poetry of Tite Kubo, a legendary manga writer who started each chapter of his Shonen jump comic Bleach with a different poem, often a haiku.

Josh Withey

Snow (1937) by Louis MacNeice

“The room was suddenly rich and the great bay-window was

“Spawning snow and pink roses against it

“Soundlessly collateral and incompatible:

“World is suddener than we fancy it.”

“Snow” encapsulates the ability poetry has to express the seemingly inexpressible.

It evokes the perception of small, everyday details of the physical world and feeling in that the overwhelming complexity of being.

Chris Baynes

To His Coy Mistress (1681) by Andrew Marvell

“Had we but world enough and time,

“This coyness, lady, were no crime...

“But at my back I always hear

“Time’s wingèd chariot hurrying near;

“And yonder all before us lie

“Deserts of vast eternity.”

Very hard to beat this for wryness of tone, the amorous narrator attempting, teasingly, to seduce his love with a memento mori – as likely a tactic as any.

The underlying seriousness of Marvell’s point about the finite nature of human existence is brilliantly evoked through its deathly imagery of graves, marble vaults and worms, which is in turn counterpoised by the poet’s zest for life and passion for earthly pleasures.

Joe Sommerlad

A Part Song (2012) by Denise Riley

“You principle of song, what are you for now

“Perking up under any spasmodic light

“To trot out your shadowed warblings?”

Sometimes poetry is no good. Denise Riley’s “A Part Song” – and the book Say Something Back from which it comes – is a brutally and meticulously good poem about why poetry is no good.

Written in the depths of grief, it finds exquisite grace in the pain of the death of the poet’s son, even while it rages at its failure to do anything about it.

Poets are among the best critics of the value of the whole endeavour, which famously “makes nothing happen”, and the deep beauty of this poem is both a stunning evisceration of poetry’s failures and one of the most glorious examples of its virtues.

Andrew Griffin

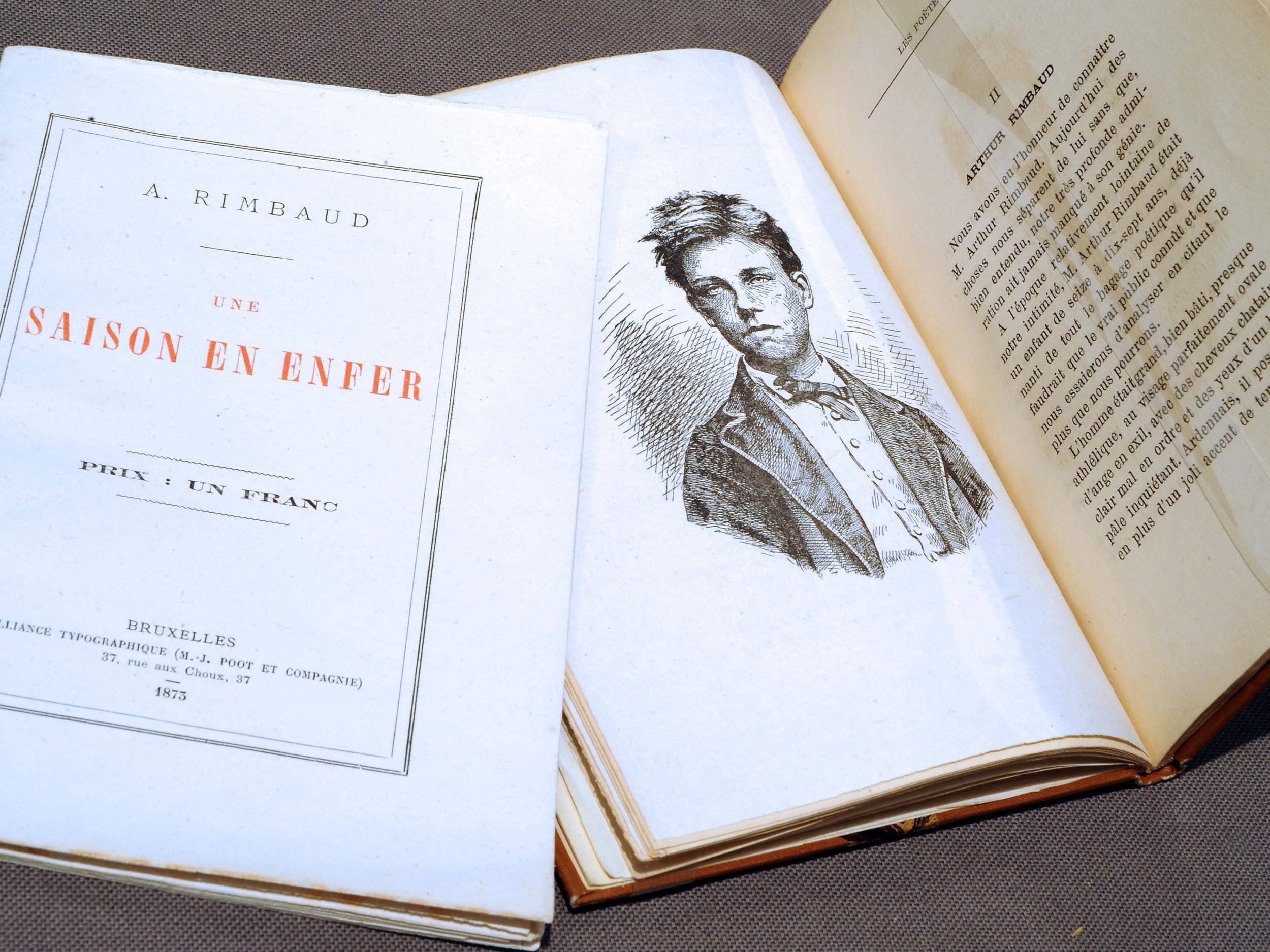

Le Bateau Ivre (1920) by Arthur Rimbaud

“But, truly, I’ve wept too much! The Dawns

“Are heartbreaking, each moon hell, each sun bitter:

“Fierce love has swallowed me in drunken torpors.

“O let my keel break! Tides draw me down!”

I think the thing that makes us fundamentally human is our ability to love. But with that ability to love comes the capacity to have our hearts broken.

What this poem reminds me of is how each time we have our hearts broken, we need to remember to embrace that pain and that sorrow, because it’s in that hurt that we feel. It’s that ache that makes us fundamentally who we are.

To me, “Le Bateau Ivre” – “The Drunken Boat” in English – and this verse in particular, sums up our entire lived experience.

Ryan Butcher

After Death (1862) by Christina Rossetti

“He did not touch the shroud, or raise the fold

“That hid my face, or take my hand in his,

“Or ruffle the smooth pillows for my head:

“He did not love me living; but once dead

“He pitied me; and very sweet it is

“To know he still is warm though I am cold.”

The youngest child of a ludicrously talented family, Christina Rossetti is one of the finest poets of the Victorian age; her work features recurring themes of the inconsistency of human love, and the perfection of the divine, with rich detail and poignant use of symbolism.

In her 1862 poem “After Death”, she addresses mortality, tragic love and the hope of an afterlife, and elects to write from the dead woman’s perspective, rather than as the man lusting after the lifeless woman beneath the shroud. It’s also one of the most beautifully written, bitter-sweet reminders that, all too often, we don’t appreciate something until after it is gone.

Roisin O’Connor

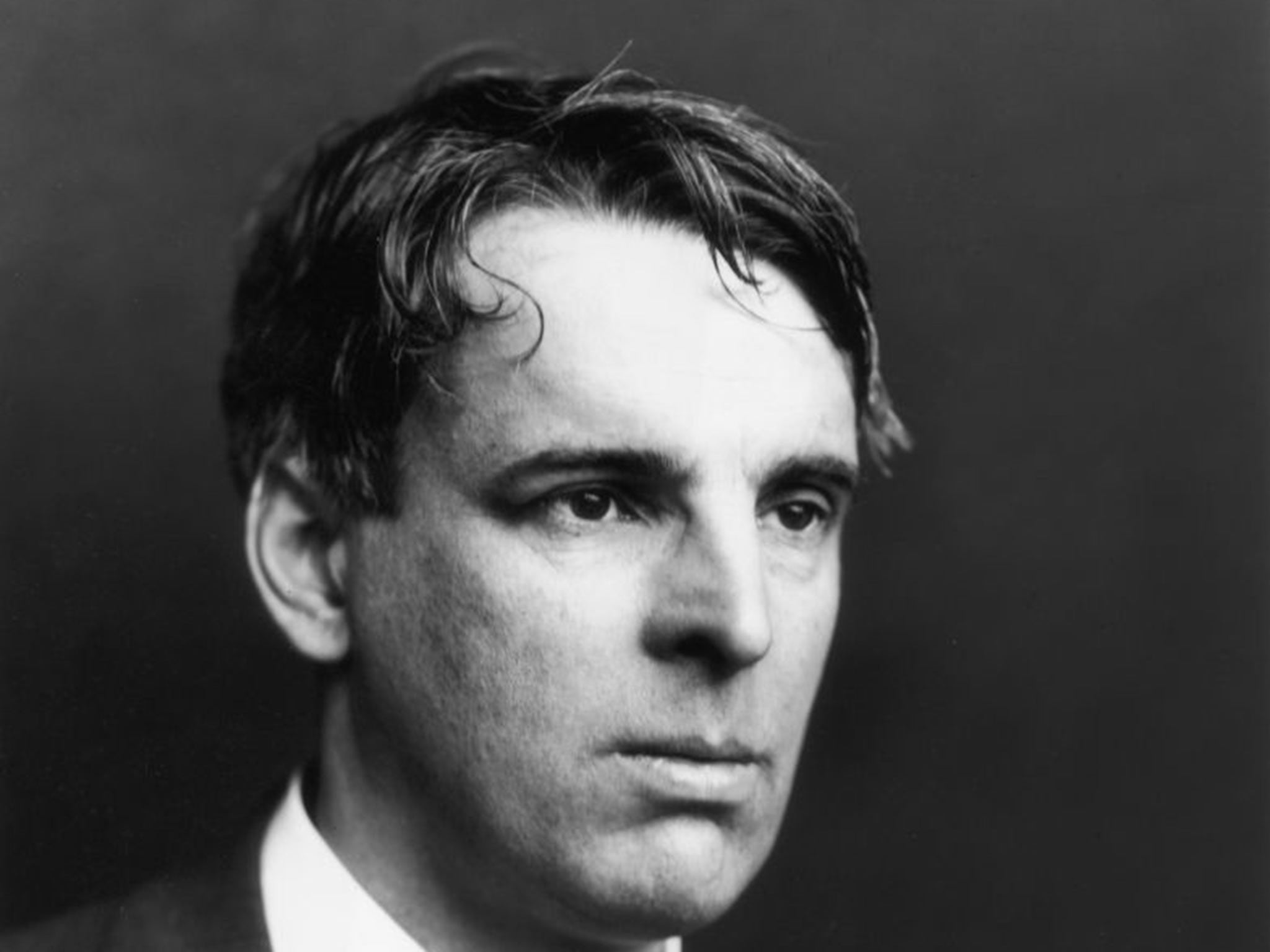

An Irish Airman Foresees his Death (1919) by WB Yeats

“I know that I shall meet my fate

“Somewhere among the clouds above;

“Those that I fight I do not hate

“Those that I guard I do not love;”

I like it because it depicts a man at peace in the most horrendous circumstance, that of a First World War fighter pilot sure of his impending death.

He isn’t comforted by a sense of duty to his country nor driven by hatred of the enemy - he’s in the air seemingly out of curiosity and is now resigned to his fate.

Liam James

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments