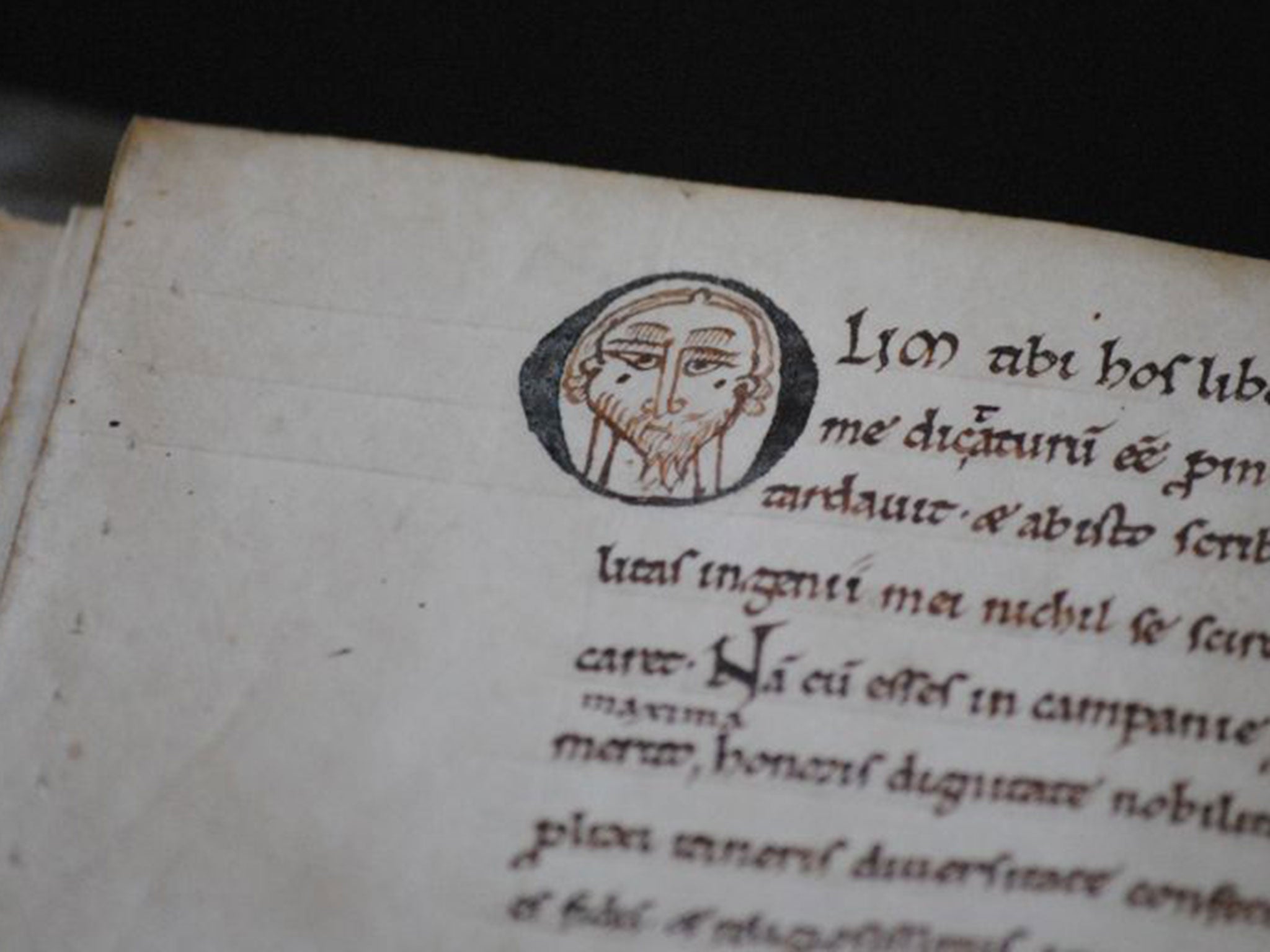

Medieval doodles prove that it's goode to scribble in ye margins

Jokey doodles and a rare bookmark are exciting scholars

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Medieval scribes got just as bored at work as you do. Hunched over piles of parchment and the heavy books they were tasked with copying, long before Gutenberg and Xerox changed everything, they responded in the same way – by doodling.

Stick men, scribbles and 1,000-year-old smiley faces adorn the margins and blank pages of the world's oldest manuscripts. For a book historian in the Netherlands, they represent a portal to a lost time, and are as rich a source of discovery as the texts themselves.

Erik Kwakkel, from Leiden University, the oldest university in the Netherlands, says there are two types of medieval doodle: the idle shapes that we all produce; and "pen trials", which scribes used to get their nibs flowing after regular cutting.

"This was a time when a book cost as much as a second-hand car today and there was no scrap paper," Kwakkel explains after revealing his latest discovery: a rare medieval bookmark. "One of the few places you could test your pen were the pages of completed books."

Some of the scribbles are elaborate and diversionary, taking longer than needed to test a pen. Others are more basic and reveal that scribes were no artists. The least imaginative doodlers would write, repeatedly, "probatio pennae" ("I test my pen").

The doodles, often made by monastic scribes who worked only for the glory of God, are "the closest we can get to the users of these books and their lives", Dr Kwakkel adds.

The 44-year-old, whose work is fascinating the modern reader via his blog and social media, has studied scribes who moved from the Netherlands to Kent. "You can see how they adapted their writing style," he says. "But when you look at their pen trials, they switch back." Dr Kwakkel uses these accidental signatures to trace the movement and work of scribes, the nameless printers and photocopiers of their time.

They also offer clues about personality and mood. Law manuscripts feature more smiley faces than other types of work, the academic says. "In general there is hardly any book that doesn't have at least one addition to the text. Some books have lots from different scribes, opening a window on the scriptorium [writing room]."

The unearthed bookmark, which is headline news in the Netherlands this weekend, had been lost for at least a century inside the pages of a manuscript at Leiden University. A circular disc that the reader could also turn to mark the column they had left, it is one of only 35 that survives, and dates to the 13th century.

"You can see thumbprints on it," Dr Kwakkel says. "You're on that level of contact with these people. It shows that manuscripts are not dead things on shelves, but almost living organisms we can use and learn so much from."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments