The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

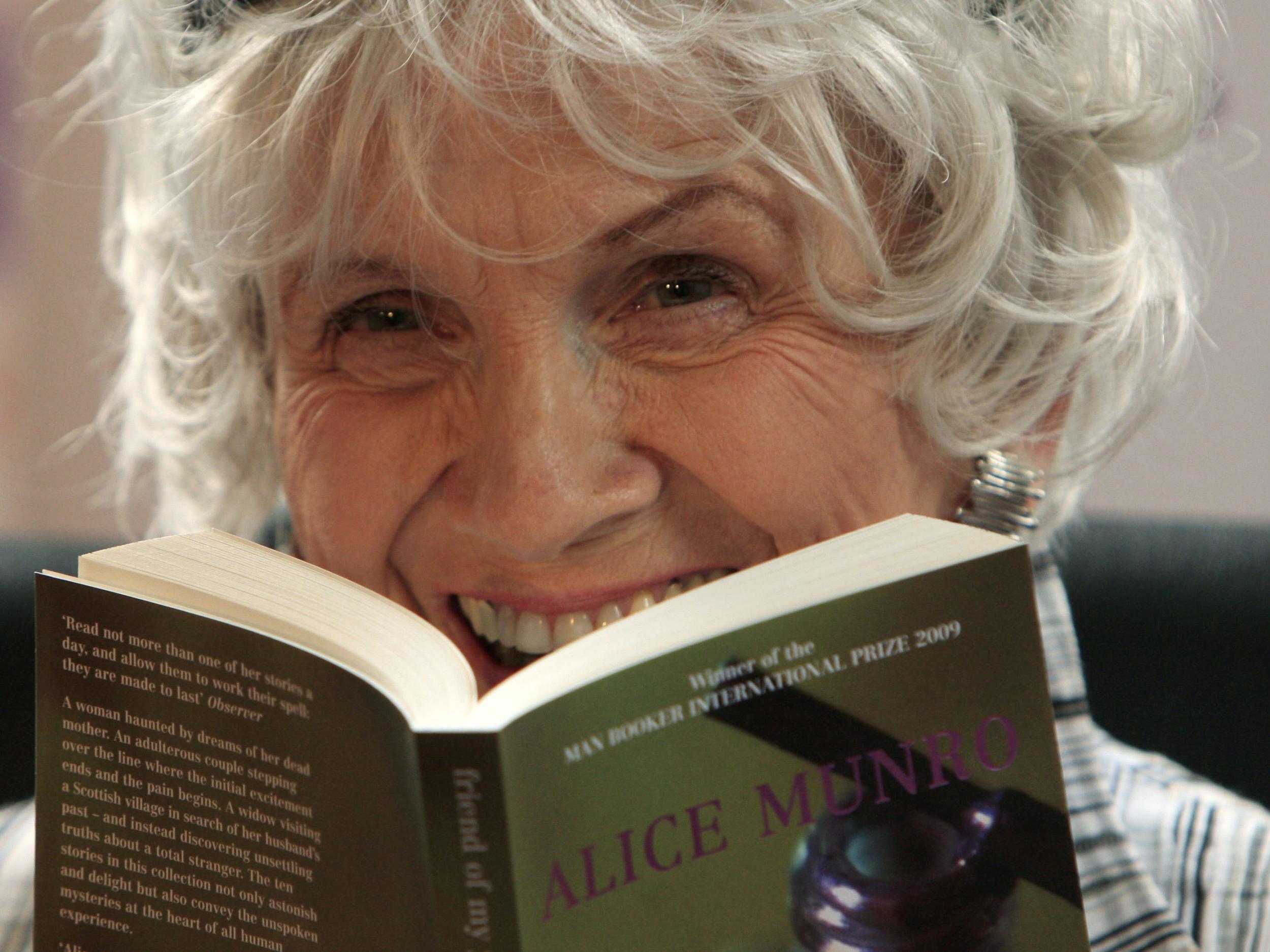

Alice Munro, Nobel Prize winning short story writer, dies aged 92

Munro, whose fans include Margaret Atwood, was one of Canada’s most acclaimed authors

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Alice Munro, the short-story writer and Nobel prize winner known as “the Canadian Chekhov”, has died aged 92. She had suffered from dementia for more than a decade.

Munro died at her care home in Ontario on Monday, 13 May, her family confirmed to The Globe and Mail.

Over the course of her illustrious career, Munro published more than a dozen collections of short stories and was honoured with the 2013 Nobel Prize in Literature and the 2009 Man Booker International Prize.

Often set in her native Huron County in rural southwestern Ontario, Munro’s stories explored complex human themes like desire, mother-daughter relationships and moral conflict. She was a master of crafting complete characters within just a few pages.

Asked after she won the Nobel Prize, “What can be so interesting in describing small-town Canadian life?” Munro replied: “You just have to be there.”

Other leading novelists were fans of her work including The Handmaid’s Tale author Margaret Atwood, a fellow Canadian who wrote an appreciation piece on Munro in 2008.

“[Munro] is among the major writers of English fiction of our time,” she wrote for The Guardian. “[Her] stories abound in such questionable seekers and well-fingered ploys. But they abound also in such insights: within any story, within any human being, there may be a dangerous treasure, a priceless ruby. A heart’s desire.”

In a 2016 interview with The Independent, Cheryl Strayed named Munro as her favourite author. “I think she's such a fantastic writer, on a craft level, to be able to create a feeling, a moment or an exchange between two characters, in ways that are so real to me,” she said.

“When I read her work I recognise the truth in it, yet she can also express things that I didn't even realise were true until I read her work.”

Munro was born Alice Ann Laidlaw in Wingham, Ontario, in 1931 during the Great Depression era. Her father, Robert Eric Laidlaw, was a fox and mink farmer and her mother, Anne Clarke Laidlaw (née Chamney), was a schoolteacher.

She married bookseller Jim Munro in 1951 and had four daughters, one of whom died shortly after birth.

After Alice and Jim Munro divorced in 1972, she married Gerald Fremlin, a cartographer and geographer whom she had met at university. Both Fremlin and Jim Munro died before her. She is survived by her daughters, Sheila, Jenny and Andrea and their families.

Munro began to write seriously in the Sixties as a stay-at-home mother when her daughters were asleep. “I was big on naps,” she told the Observer in 2005.

Her first collection of stories, Dance of the Happy Shades, was published in 1968 and won the Governor General’s Award, then Canada’s highest literary prize. She intended to write a novel, but said that with three children there simply wasn’t the time.

“For years and years, I thought that stories were just practice, ‘til I got time to write a novel. Then I found that they were all I could do and so I faced that. I suppose that my trying to get so much into stories has been a compensation,” Munro told The New Yorker in 2012.

From the 1980s to 2012, Munro published a short-story collection at least once every four years, concluding with Dear Life. In 2009, she revealed she had undergone heart bypass surgery and had been treated for cancer.

“My stories have gotten around quite remarkably for short stories,” she told the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation after winning the National Book Critics Circle Award.

“I would really hope that this would make people see the short story as an important art, not something you play around with until you got a novel written.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments