A graphic history of US civil rights – in comic book form

A veteran of the Fifties campaigns is inspiring a new generation of activists

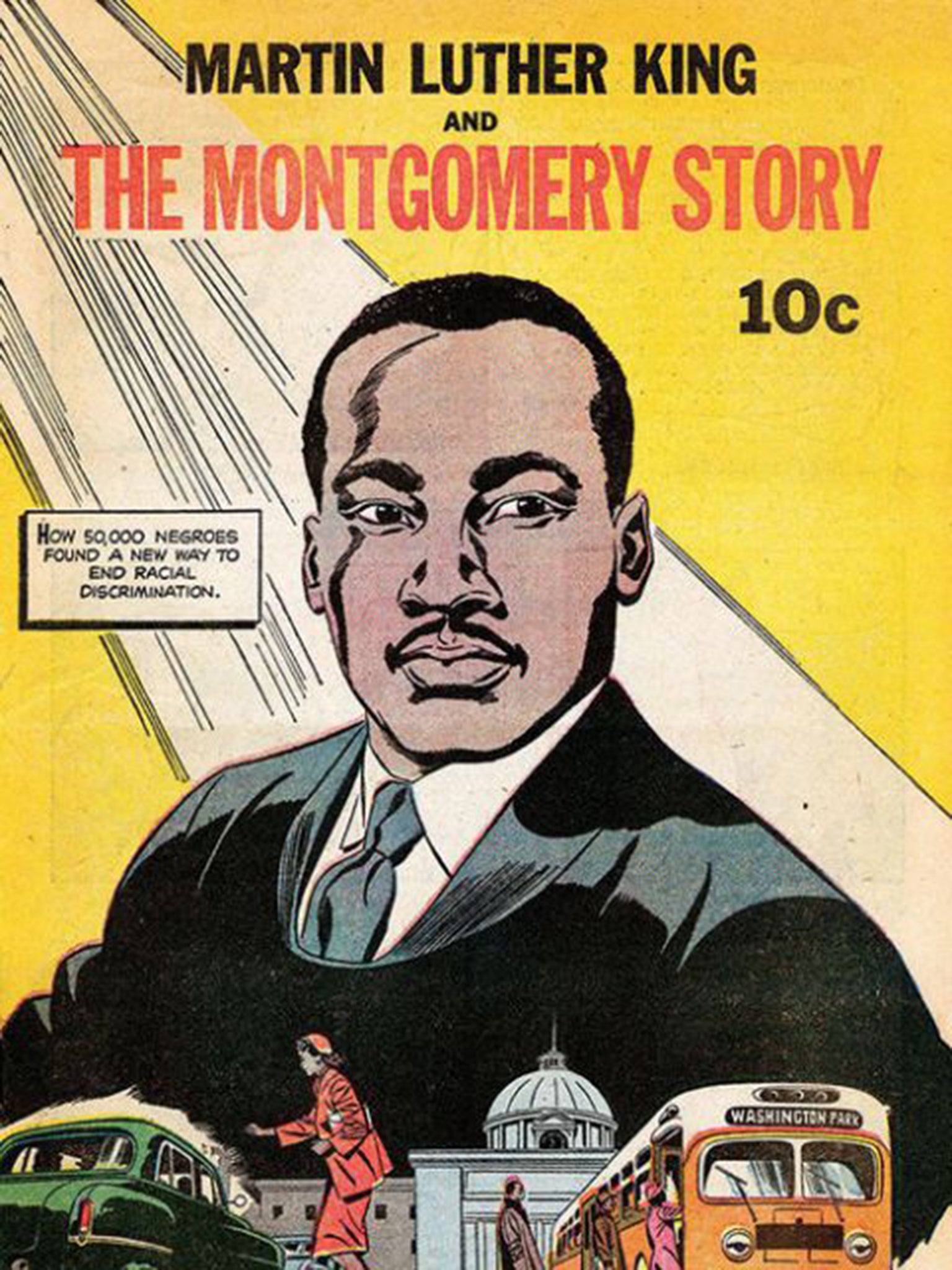

In 1956, the US civil rights campaign group Fellowship of Reconciliation sought to raise awareness of the movement by publishing a comic book about Martin Luther King, Jr and his leadership of that year’s Montgomery bus boycott. Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story not only recounted King’s biography, it also outlined his principles of non-violence and how to enact them.

Some 250,000 copies were printed on cheap paper and distributed across the South for 10 cents each. One fell into the hands of John Lewis, the teenage son of rural Alabama sharecroppers, who would go on to be the youngest of the so-called “Big Six” civil rights leaders and a close colleague of Dr King. His participation in the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches made him a national figure, as depicted in the Oscar-nominated film, Selma, released in the UK next month.

Now Lewis, 74, a 15-term US congressman for Georgia’s fifth district, is turning his own experience of the civil rights era into a comic book, in the hope that it will inspire a new generation of activists. The second volume of his graphic memoir trilogy, March, was published in the US this week by Top Shelf, illustrated by Nate Powell and co-written by Lewis’s aide, Andrew Aydin.

It was Aydin, a self-confessed comics “fanboy”, who first had the idea for March, after Lewis mentioned The Montgomery Story to him on the 2008 campaign trail. “He’d talked a lot about how to interest young people in the political process, and how to teach them about the civil rights movement,” Aydin recalls. “I thought, ‘Why doesn’t he write a comic book?’ I asked him several times and he finally said he said he’d do it, but I only if I wrote it with him.”

While writing the first volume of March, Aydin also completed a master’s thesis about the influence of The Montgomery Story on Lewis and others. He learned that comics had been widely used by civil rights organisations, including the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, of which Lewis was chairman from 1963 to 1966. “They were dealing with semi-literate populations, so the pictures helped folks to understand what they were trying to convey,” Aydin says.

The first volume of March, which covers Lewis’s youth and early activism, was published in 2013 and became a New York Times bestseller. It is now used as a teaching tool at schools and colleges in at least 40 US states. A good thing too, says Aydin, who describes the current state of civil rights education in American schools as “awful”.

A recent report by the Southern Poverty Law Centre gave more than half the states in the US a D or F grade for their teaching of civil rights. “More and more we hear from people who watched Selma or read March and they ask, ‘Was it really that bad?’ That’s why it’s so important to tell this story today,” Aydin says. “People need to re-examine our past if they’re going to change our future.”

The second volume of the trilogy begins in 1960, when Lewis was among the first “Freedom Riders”, a group of white and black activists who travelled through the segregated South on the same bus, enduring beatings, arrests and Klan intimidation. It climaxes three years later, when he helped to organise the historic March on Washington, where King delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Lewis, then 23, was the youngest speaker that day, and is now the last surviving.

March could not have been published at a more apt moment, in the aftermath of several high-profile police killings of unarmed black men and the protests that followed. Lewis, Aydin and their publishers sent several copies of the book to the public library in Ferguson, Missouri, where in November a grand jury declined to indict officer Darren Wilson in the death of Michael Brown.

The authors also spoke at Louisiana State University, where several students subsequently formed a campaign group, Baton Rouge Organising, based on the 1960s national student movement they had read about in March. “It is my hope and my wish that more and more of the young people engaging in non-violent protests would take a lesson from March and use the way of non-violence,” Lewis recently told ABC News. “But I’m gratified to see young people not being so silent. That they’re speaking out, and saying that we’re going to continue to push forward.”

Meanwhile The Montgomery Story has also enjoyed a new lease of life. Top Shelf republished the 59-year-old comic in the US, while in the Middle East it was translated into Arabic and Farsi and published online by an activist hoping to inspire non-violent protest. In 2011, copies of King’s story were reportedly passed around in Cairo’s Tahrir Square, the cradle of the Arab Spring.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments