Jenny Lawson: On her new book and how Covid killed her granny twice

Author and blogger Jenny Lawson talks about her pandemic year and her new book ‘Broken’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

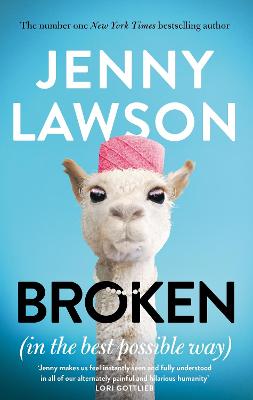

Your support makes all the difference.Jenny Lawson’s left shoes are called Thelmas; the rights are Louises. She has a cat named Hunter S Thomcat and has christened a backyard owl she tried to befriend Owly McBeal. On a frantic mission to fashion booties for her dog, Dorothy Barker, she earnestly asked a drugstore clerk for “toddler-sized” condoms. During her 14-year career as an award-winning blogger (of the Bloggess) and author – her recently released Broken (in the Best Possible Way) is her fourth book and fourth consecutive bestseller – she’s penned an inordinate number of stories about squirrels.

Lawson may sound twee and sentimental, like Jess from New Girl, and with a knack for awkwardly derailing social interactions like Liz from 30 Rock. But the sitcom-esque bits are simply candy coating a hard pill to swallow – the dark depths of Lawson’s years-long battle with depression, anxiety disorder and autoimmune diseases.

In Broken, Lawson is honest about her physical and mental health, but her levity (often in CAPS) is her buoy and her brand. Life with these ailments may be brutal, but she insists it can also be funny, like the painful joint-swelling from rheumatoid arthritis that sends her stretched-out shoes flying off her feet in public places, including into a movie theatre toilet. “I think the comedy helps people who don’t necessarily have my same battles want to keep reading,” she tells The Washington Post, “and also maybe have a better idea of what it’s like to deal with mental illness or chronic pain.”

Q: When you started the Bloggess, could you have imagined the accolades and bestselling memoirs?

In some ways, the pandemic is a marathon I’ve been preparing for my whole life. In theory, it sounds sort of amazing to fall into being a full recluse, but this has made me a bit more fragile mentally

A: If you’d told me it would lead to four New York Times bestsellers, I’d have thought you were even crazier than I am. My social anxiety makes it incredibly hard for me to have normal small talk, so blogging has been the next best thing. I can reach out and share my weird thoughts and find the people who also wonder why Jesus isn’t considered a zombie.

Q: In the book, you write about trying transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), an experimental depression treatment that sends electric currents to specific parts of your brain. The currents made you wink involuntarily, and you joked to a room of medical students that you weren’t trying to seduce them. Why do you think you have an impulse to be funny in the midst of something serious?

A: Mental illness can really seem like a monster – this out-of-control thing that, at any moment, can reach out and kill you. There’s something about laughing at a monster that makes it smaller, more manageable.

Q: While at your wit’s end you wrote an open letter to your health insurance company – who’d denied you game-changing medicines and treatments and imposed penalties on the medicines they did cover. In your letter, you write, “You say you have my best interest at heart. You are not even a good liar. I’m embarrassed for us both.” You actually submitted it and finally got approved for TMS. Did you ever get feedback from anyone who read it?

A: I never got feedback from the company, but I’ve already had so much feedback from people reading my book – and that chapter is the one that resonates with so many. Which is sort of terrible, because not being able to get coverage for the things that let you live is absolutely absurd.

Q: You revealed that the insurance agents you spoke tirelessly with “tell me they deal with the same problems. They are us.” What was that like, to realise the people denying your claims are dealing with a system so broken that they themselves are powerless against it?

A: In a way, it was empowering, because it made me realise that I’m saying to them what they want to say to their own bosses. Yelling at them is pointless and cruel – they are in the same boat as the rest of us. If you ask, “What would you do in my shoes?” they will often give you feedback or hints in getting around the endless red tape and denials because they know, at least a little, how to work a system that is designed to make you give up.

Q: You write, “I am bad at people to the point where I sometimes fantasise about how great house arrest might be.” I imagine there are ways the pandemic has suited you, but also ways you’ve felt overwhelmed, as someone at high risk. What has been gratifying during the past year? And what hasn’t?

A: In some ways, the pandemic is a marathon I’ve been preparing for my whole life. In theory, it sounds sort of amazing to fall into being a full recluse, but this has made me a bit more fragile mentally. It’s so easy to fall into an unhealthy introversion and become isolated. My grandmother died of Covid – twice, actually, because they had so many patients, they got confused and told us she’d died when she was alive – and it was awful knowing that she was alone and not being able to be there for her burial.

Q: Your grandmother died of Covid twice? That is uniquely terrible, even for this past year.

A: She was in a memory care clinic; she had dementia. We try to laugh about things that are hard in my family, and we always had this joke that she was immortal. She would fall, and they would be like, “She’s not gonna make it through [this],” so my mum would sit with her overnight, and then the next day she would wake up and be like, “Well, why are you here? I’m ready for breakfast.” Just over and over. My mum was like, “She is unkillable. She’s immortal!” We knew she’d been in the hospital with Covid – she was the first person in her clinic who got it. Nobody was allowed in, so my mum would get calls from the hospice and a hospice nurse told her Granny had passed away. I was like, “Are you sure, Mum? She’s so tough. She’s probably still alive there somewhere.” She’s like, “Nope, pretty sure.”

So she makes arrangements and sends the coroner out, and maybe five hours later, she says, “You were right. She’s still alive.” What we think happened is the hospice nurse got the wrong information from the nurses that worked there – and the hospice lady was, of course, beside herself: “I’m so sorry, oh my God...” But my granny’s parents and parents’ parents all had dementia, and when my great-grandparents got it, I remember her being like, “Oh God, don’t let me live through this. Take me out to the woods.” So you have these mixed emotions of, “Yay, Granny’s not dead! But she probably wants to be?” My mum was like, “I just know she would not want to be here anymore.” The doctor told us she wasn’t going to make it through another night; and the next morning they called, and my mum said, “She did it for real this time. I think.” It was a 100 per cent the way my grandmother would want to go, to keep us guessing. It’s like she gave us this one last story. We have some family members who are like, “Covid’s not real!” And my sister’s like, “Oh, really? Because it killed my granny twice.”

Broken (In the Best Possible Way) by Jenny Lawson. Pan Macmillan, £14.99

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments