How classic comics gave way to garish magazines

Todays children’s magazines are a far cry from the likes of The Dandy and The Beano. But David Barnett finds one that is reviving the lost art of the type comics he so fondly remembers from his youth

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For anyone who grew up in the Eighties or earlier, the supermarket racks of children’s comics in 2016 make for rather bleak browsing.

At the risk of going all “jumpers for goal-posts” and “it was all fields round here when I were a lad”, those halcyon days of yore feel like a forgotten world, where every newsagents was a cornucopia of delights, a little shop of curiosities, filled to the brim with proper comics, each one overflowing with adventure, amusement and sometimes anarchy.

Their titles are like a roll-call of the half-remembered… Monster Fun, Shiver & Shake, Smash!, Krazy, Buster, Bunty, Judy, Hotspur, The Dandy…

And what do we have now? Rows and rows of garish polybagged publications, tacky plastic free gifts stuck to the cover, pages and pages of what feel like extended adverts for the latest Disney film or video game, interminable tips for Minecraft and Pokemon Go… and rarely an actual comic strip in sight.

“The traditional comics market has definitely diminished over the years,” says Lew Stringer, a comic artist of 30 years’ experience who also runs a blog about British comics at lewstringercomics.blogspot.co.uk. “The shelves are still packed with titles aimed at children, but now they’re magazines with little or no comics content. It was a gradual change that happened over several decades but it wasn’t unexpected. British comics have always evolved and this is just the current state of play. It’s not ideal for comics creators but there’s still strips in some titles and many of us are still busy drawing them.”

“We have to be careful what we’re calling ‘comics’,” adds Jamie Smart. “Most titles on the newsstands I think could be called magazines rather than comics – they might have a few pages of comics in there, but the majority is articles and editorial, and most of that is about Marvel or Lego or things like that.

“Alongside that there are licensed character titles, like Peppa Pig or The Simpsons, and some of them might be more comic-based. But an actual comic, full of original characters and stories every week or fortnight, well that’s still a rarity in the UK at the moment.”

Both Stringer and Smart are comic creators plying their trade in this somewhat challenging market. Smart has worked on The Dandy, with his own creations and also on big names from their stable of well-loved characters, which included Desperate Dan, Korky the Cat and Bananaman. Anyone who has not yet dipped a toe back into the world of children’s comics, perhaps with children of their own, might be surprised and dismayed to learn that The Dandy, established 80 years ago in 1937, actually ceased publication in 2012.

Smart was the writer and artist for Desperate Dan for five years before The Dandy went online only, and thereafter died, which he says was “a great honour”. He’s also done Roger the Dodger for The Beano, and worked on more modern titles such as Toxic, Mega and Doctor Who Adventures.

But if the comics us oldies know and love have more or less ceased to be, who’s still keeping the flame for the British children’s story papers? “There are still a smattering of original strips, if you know where to find them. Stringer, another Beano alumnus, says, “Myself and others are producing original non-licensed strips for Toxic and Epic magazines every month, and titles such as Danger Mouse and Doctor Who Adventures feature exclusive comic strips. Toxic has been around for 15 years now and although it’s mainly feature-based content it does include several pages of strips every issue.”

And in and among the rows of licensed mags and Lego promotions, you might spot one familiar name peaking out; British comics’ great survivor.

Smart says: “Really, it’s only The Beano and The Phoenix that are really representing there now.”

The Beano we all know, the home of the mighty Dennis the Menace, Minnie the Minx and the Bash Street Kids, which at its height in the 1950s was selling close to two million copies every single week. It’s something of a comfort to know it’s still going, in the same way that it used to apparently be British policy that in the event of a nuclear war, if the Today programme was still on Radio 4 then civilisation in Blighty still endured.

But what is The Phoenix? Well, it just might be the British magazine industry’s best kept secret, and quite possibly the saviour of the entire concept of kids’ comics. But it’s no newcomer; in fact, The Phoenix has just celebrated its fifth anniversary.

“We’re trying to be pioneers, bringing comics back to people in the UK,” says Tom Fickling, editor of the Oxford-based Phoenix. “We’re really the only people publishing completely original content rather than just licensing characters.”

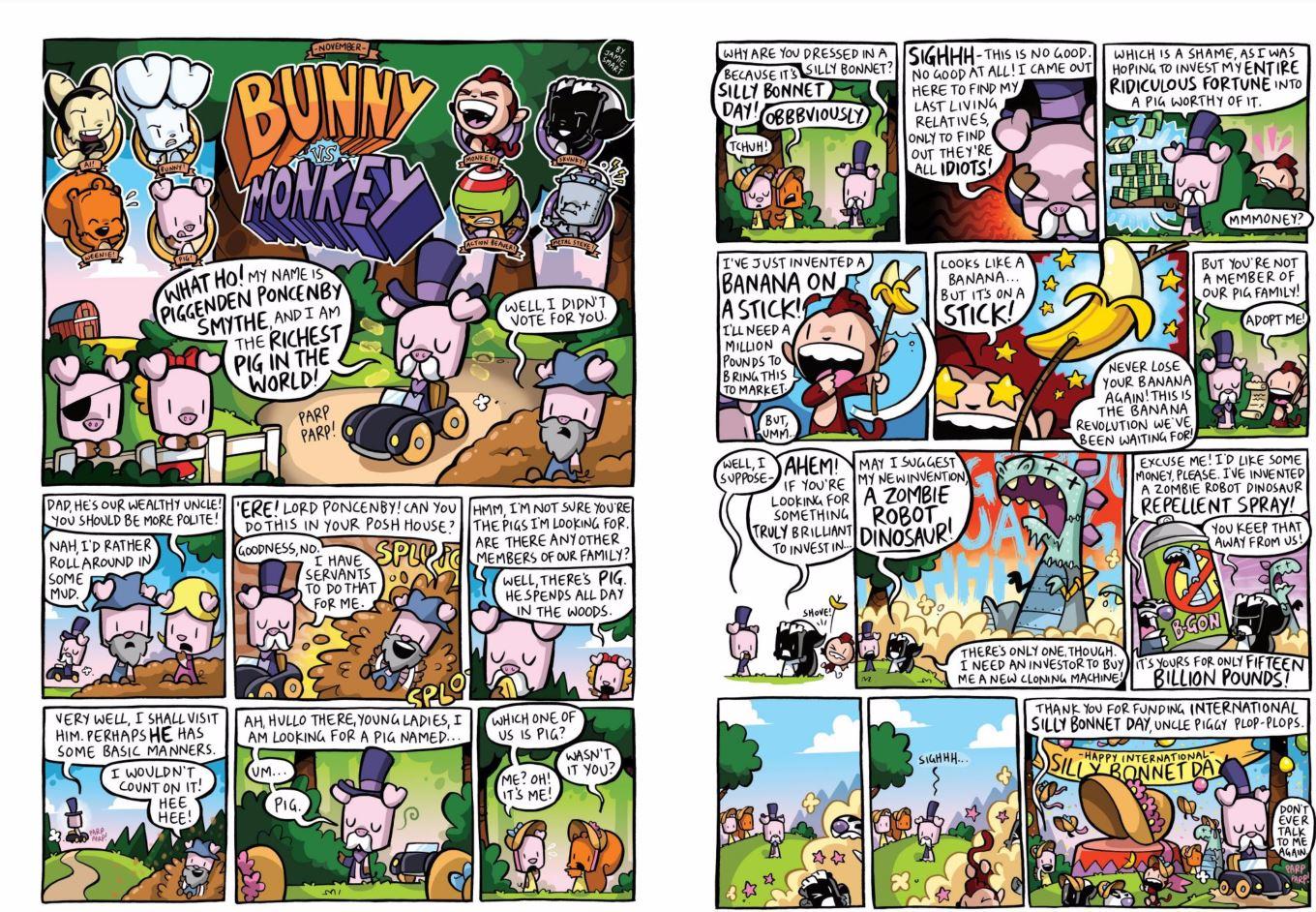

The Phoenix is 32 glossy pages with not an ad in sight. Save for a couple of editorial pages, and some showcases of reader art and letters, it’s comics. All comics. From the space adventure of Trailblazer, to the comedy of Evil Emperor Penguin, through the slapstick anarchy of Bunny vs Monkey, and the high-octane thrills of Mega Robot Bros, to The Adventures of John Blake – written by none other than children’s author Philip Pullman, with art by Fred Fordham – The Phoenix is a joyful return to pure sequential art for younger readers.

The idea really came from Tom’s father, David, who runs the children’s publisher David Fickling Books. He was born in 1953 and raised on a diet of Eagle and, says Tom, always appreciated the value of comics. Tom says, “He thought they were brilliant in terms of encouraging a love of reading in children. A lot of his career has been about promoting literacy and reading for pleasure, and he felt comics played a major role in this.”

In 2007 David Fickling launched his own comic, in conjunction with publisher Random House and other investors, to promote these values and also as a bulwark against the waves of glossy but superficial children’s mags filling the shelves. It was called The DFC and it was heralded as a bold return to form for comics. Unfortunately, it was launched just as the global credit crunch hit, and as companies tightened their belts, the funding for it eventually collapsed after it had run for 43 weekly issues.

Then, in 2012, four years after the DFC had closed, David’s son Tom launched The Phoenix, building on the work of the DFC, its name a nod to both the fact it had risen from the ashes of the first experiment and the synergy with the classic comic that had first inspired David, the Eagle.

So where is it on the supermarket shelves, and why haven’t you heard of it? That’s probably to do with The Phoenix’s distribution model; it’s subscription only. Thanks to a deal with the pro-literacy supermarket chain Waitrose you can find it on the shelves there, and also in specialist comic shops that more usually deal with the American monthly comic books. But generally if you want to read it, you buy a subscription online and it’s delivered through your letterbox every Friday.

“That probably seems very middle class,” admits Tom. “But that’s not at all what The Phoenix is about.”

But wouldn’t it reach a far greater audience if it was on the shelves next to everything else? “Absolutely,” he says. “I fully agree; The Phoenix should be everywhere. But we just don’t have the marketing budget to do that. It can cost £3,000 a fortnight to just get a comic stocked in some supermarkets. We are putting our money into providing original content, paying creators to write and draw quality comic strips.”

Those who do get The Phoenix through subscription love it. “We have a broad range of readers, aged usually between six and 12 but with some on either side of that, and it’s the highlight of their week when the comic arrives. We’ve a fairly equal gender split and some of them are voracious readers, some are reluctant readers who don’t read anything but The Phoenix.”

Slowly though, the word is getting out. Tom has a policy of collecting the episodes of individual strips together for “box-set” releases; Corpse Talk, by Adam Murphy, sees the author and artist “interviewing” famous dead people, and in 2015 it was the first comic to be nominated for the Blue Peter Book Award. Murphy’s follow-up book, Lost Tales, an examination in comic form of folklore and myths, has done the double and is shortlisted for this year’s awards.

Murphy’s work sniffs almost of being educational, but the kids would never know it. Similarly, Neil Cameron’s Mega Robot Bros is actually a masterclass in diversity storytelling, wrapped up in a story of super-powered robots having adventures.

“We have an amazing team behind The Phoenix,” says Tom. “People have worked tirelessly over the past five years to get us where we are. And our creators are incredible.” One of those is Jamie Smart, whose strip Bunny vs Monkey has been a mainstay of The Phoenix since the beginning. “People in the UK need to wake up to Jamie Smart,” says Tom. “Though he’d be too modest to say that himself.”

Instead, Smart will happily sing the praises of The Phoenix. “To have a title which every week serves up original, fresh content, in print, for children but enjoyed by all is amazing. I veer towards the sillier, cuter end of the scale with my contribution but there’s such a range in there, so many different genres of comic they print, and all of it really high quality stuff. Nothing recycled, nothing phoned in. It should be part of the school curriculum.

“Also, having worked with the team there for the last five years, I’m constantly bowled over by how passionate they are about this. They care about comics, they care about making good comics, and that’s actually quite rare in publishing. The Phoenix heralds a new renaissance for children’s comics, and I say that not as an artist, but as a fan.”

Lew Stringer, also, has a lot of love for The Phoenix. He says: “I like the fact that there’s no house style to the art as that gives a nice variety to the comic. It keeps things fresh.

“The Phoenix has done remarkably well to exist mainly through subscriptions for five years. It’s something that only an independent comic like that could achieve. I doubt mainstream publishers would base a comic around a subscription model but as newsstand sales decline anything is possible. I hope the success of The Phoenix encourages other small publishers to try that model.”

But what of the future of comics? Stringer says: “I don't think we’re likely to see a return to the days of the mid-to-late 20th Century when originated weekly comics were the norm, any more than we’re likely to see 19th Century ‘penny dreadfuls’ return. For over 20 years now, retailers have come to expect children’s comics/magazines to have a tie-in to TV shows, toys, etc and they’re unlikely to order something they’re unfamiliar with. The Beano survives because it’s a title parents and retailers recognise, but a brand new non-licensed comic would struggle to even get on to the shelves. The bagged toys and cover mounts were also at the suggestion of retail giants so that’s not likely to change anytime soon.”

Smart is hopeful, like Stringer, that The Phoenix might inspire others. “Setting up a new children’s comic is a risk, a big risk, with a million different hurdles. So it’s going to take the passionate few, like The Phoenix, to push through and lead by example. Then, hopefully, other titles will spring up around them.”

“I’ve done a lot of workshops where the kids are so excited about comics, and want to get really involved in making their own. The passion for reading and creating comics is there, in children, we just need to work on actually getting comics in front of them. To do that we as a culture need to learn how to enjoy comics again.”

The Phoenix is offering an exclusive introductory offer for The Independent readers to sample five issues of the comic for just £1 if they buy a quarterly subscription. For more details go to www.thephoenixcomic.co.uk/inde17

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments