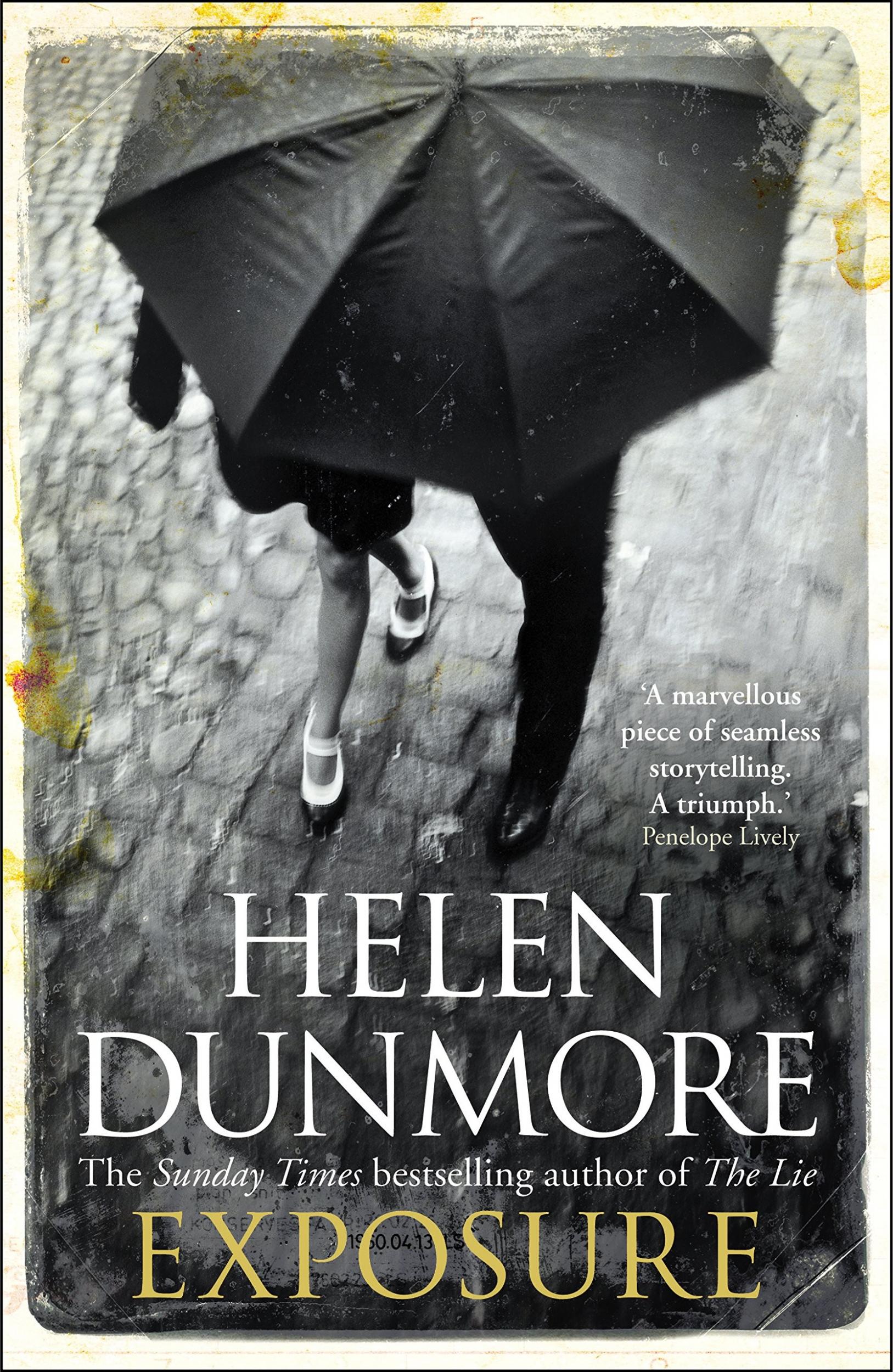

Helen Dunmore, Exposure: 'A whistlestop tour through the Cold War, with extra veg', book review

Helen Dunmore delivers a deceptively simple masterpiece, a new take on the lives of the men and – particularly – women caught up in the Cold War.

A train whistle blows. It sends a shudder through Lily Callington, as she digs over the vegetable patch in her garden in the north London suburbs in the autumn of 1960. She is Jewish, of German origin, and a train whistle brings back childhood horrors. But she tells herself: “You are standing on your own patch of earth. Your name is Lily Callington. You are in England now.”

The same train whistle is heard by Giles Holloway, a man in his forties mooching through Finsbury Park. For him, the sound means escape.

“He knows exactly which train he will catch, if he ever needs to disappear.” An idealist before the war, he joined an inner circle and learned to hide his true beliefs in plain sight; now he’s tired, disillusioned, working under cover in Whitehall. Doing things that could get him killed.

The train whistle is also heard by Paul, the young son of Lily Callington and her husband, Simon. They have a life together in the suburbs. But Simon works with Giles, who has a favour to ask that will shift the earth from under Lily’s feet.

Two decades after she won the inaugural Orange Prize for Fiction, Helen Dunmore delivers a deceptively simple masterpiece, a new take on the lives of the men and – particularly – women caught up in the Cold War.

The title of the story suggests exposure to extremes, perhaps of temperatures. Hot and cold. It also suggests the sudden opening of an aperture letting light flood in on to film, revealing what was hidden, causing chemical reactions that change everything and create a new image. There’s a roll of film in the briefcase that Simon fetches from his office for Giles.

The story twists and turns and is multi-layered, of course, as is the nature of spy tales; but Exposure is different. There is a page-turning quality that makes you wonder if this really can be a great book. They usually make you work harder than this, don’t they? Not always, is the answer. Not this time.

Dunmore’s exquisite craft as a story teller lies hidden well beneath the surface of a compelling thriller, albeit one that is defiantly and brilliantly domestic.

Spies are not really like James Bond. They live quiet, ordinary lives in the suburbs: watching, recording, but seldom drawing attention to themselves (unless, like Giles, their cover involves being just a little flamboyant at times, the life and soul of the party). When their deeds are exposed, so to speak, the chemical reactions change the lives of the people they love: their wives, their lovers, their children, and those consequences are explored in deeply moving detail here.

Simon and Giles and other men are footsoldiers in a great, silent war. For all their high designs or good intentions, they don’t know what they are doing most of the time, nor what is being done to them. But this is really the story of Lily, a woman who thinks she is safe from the past but then has to find the strength to survive one more time.

She must work out what is right and wrong, who is lying and who is not and somehow imagine – yet again – a new life, then will it into being. Whatever it takes. She is heroic, in secret.

The intimacy of the language, a voice whispering a commentary in your ear, takes you into Lily’s world. So do the telling details of life, from the train whistle in the air over Muswell Hill to the chopped and steamed Savoy cabbage she puts on the table. “She cooks it with caraway seeds and finishes it with butter.” Her cooking makes her husband feel like he is part of a secret society, says the narrator with a gentle irony.

For all her determination to be safely English, Lily will not give up taste and sensation in a world that is still all too drab, grey and austere. The kids have noticed it too. “Only the Jewish homes offer the intensity of taste and texture with which they are familiar.”

These are not major plot points – no spoilers here – but they illustrate the way Dunmore makes domestic detail serve her characters and her story, almost without the reader noticing. You breathe it all in, like the scent of the cabbage. There is death and high drama here, but it all happens in a time and place that is now alien to us but feels intimate and real.

Helen Dunmore is also a poet, and her prose is like poetry in its precision: the insistence on the right word, the right pause to create the mood. Hints and subtleties emerge on a second reading that are hidden during the first, when the story drives you forward with a determination to find out what happens. You will care. Quietly, deceptively, Exposure is magnificent.

Exposure, by Helen Dunmore. Hutchinson £16.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments