World War Z author Max Brooks honours WW1's Harlem Hellfighters in new graphic novel

The Harlem Hellfighters are some forgotten heroes of 1918. Brooks talks about race, legacy and his Will Smith film option to Tim Walker

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The US 369th Infantry Regiment was the first Allied unit to reach the Rhine as the First World War came to an end in 1918. Its soldiers had spent 191 days in combat, more than any other American troops. Nicknamed the "Harlem Hellfighters" by the Germans, they were one of the most decorated units in the American Expeditionary Force. And yet, in the years that followed, they were all but forgotten by the American people. Why? Because they were black.

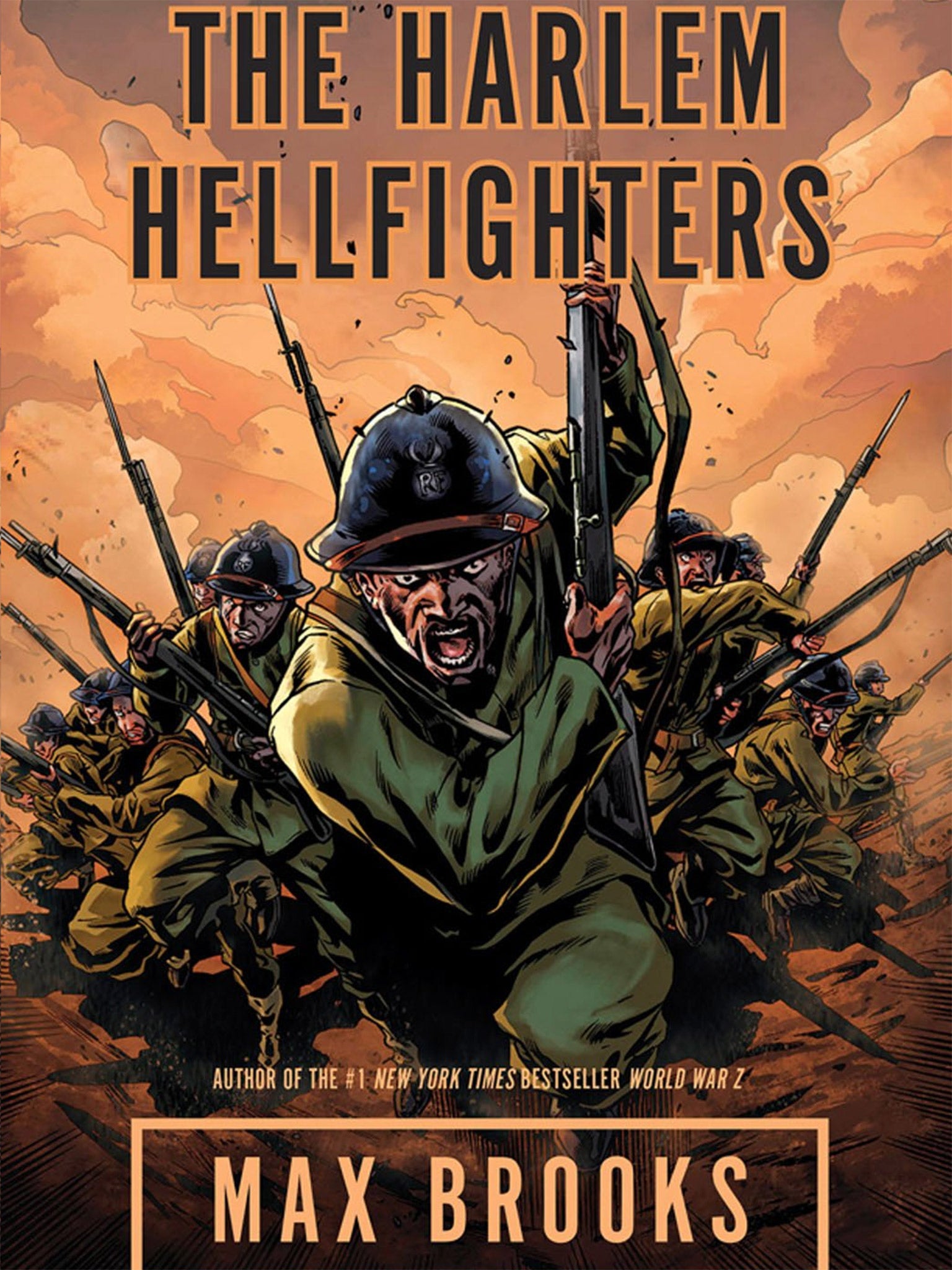

A century later, the men of the 369th are at last commemorated in The Harlem Hellfighters, a new graphic novel by Max Brooks, author of World War Z, and the artist Caanan White. The book has been well received: this newspaper praised White's "brutal, visceral" style and the "propulsive vigour" of Brooks' narrative, the whole making "an angry, restless statement". It tells how the unit was trained in the US, but fought alongside the French, the only Allied army to accept black troops. The Hellfighters distinguished themselves in battle – one, Henry Johnson, was the first American soldier awarded the Croix de Guerre – but the US authorities suppressed news of their heroism, and ensured they were never treated as equals.

"The Hellfighters might have been the only soldiers in that whole stupid war who were actually fighting for something," Brooks says. "They fought to prove their worth as citizens and men. They actually had a cause – whereas all those poor British and French and German boys just got chewed up for no reason. It's shocking how little presence they have in our national culture. America is so proud of the strides it has made in diversity, yet this story was left to the ash heap of history."

Brooks, 42, has waited years to tell the Hellfighters' story. He first heard it himself when he was 11, from a student who worked for his parents, the comedy auteur Mel Brooks and the actress Anne Bancroft (whose own works about racism must have contributed to his ethical framework). Still intrigued after studying the world wars in college, he went in search of more material about the men who battled an enemy abroad and brutal prejudice at home, but he found it peculiarly hard to come by. "My very first Amazon purchase, in the 1990s, was the one book I could find about the Harlem Hellfighters," he says. "But when it arrived, it was only 80 or 90 pages long."

Finally, he came across From Harlem to the Rhine, a rare first-person account of the Hellfighters' exploits, written in the 1920s by a white officer, Arthur Little. Brooks decided to turn the tale into a screenplay, but it soon became clear that his script would not sell well in Hollywood. "The First World War was not on anyone's radar in the late 1990s, and there were very few black movies that made money back then," he recalls. "I took a screenwriting class at UCLA from a guy named Stephen Duncan, who was African-American, and he told us: 'If you make your protagonists anything other than white men, you're closing a lot of doors.' As he was saying it, Harlem Hellfighters was getting rejected all over town."

Brooks was in good company. George Lucas, the Star Wars creator, spent almost 25 years trying to bring the story of the Tuskegee Airmen, a group of African-American pilots who fought in the Second World War, to the screen. Red Tails was finally released in 2012.

Now, during the First World War centenary, and with "black movies" such as 12 Years a Slave and The Butler making upwards of $100m (£66m) at the box office, Brooks has written a new film version of Harlem Hellfighters, based on his book, which is being developed by Will Smith's company, Overbrook. This year's Oscar nominations were faulted for demonstrating the lack of diversity in US film, but Brooks says: "Hollywood isn't racist; it's greedy. And when a movie starring black people made $100m, everybody took notice. If people think movies can make money, they'll green-light them."

Despite his Hollywood pedigree, Brooks has always thought of himself as an author first and a screenwriter second; he wrote his first novel at 15. Yet he also suffers from dyslexia, and as a boy he found comics an easy and valuable way to consume literature. "I'd love to say it was Mark Twain who turned me on to reading," he says. "But I probably owe just as much to Rom the Spaceknight."

His first published novel, the gripping World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie War, became a bestseller after its release in 2006. (Though Brooks borrowed his zombies from horror legend George Romero, the book's international, epistolary structure was inspired by Studs Terkel's 1984 non-fiction doorstop, The Good War: An Oral History of World War Two.) He was not directly involved in the 2013 Brad Pitt movie adaptation, which bore little resemblance to his original text, but he says: "It's a really good movie that just happened to have the title of a book I once wrote."

There is a knowing reference to zombies in The Harlem Hellfighters, when Brooks and White depict soldiers suffering from shell-shock. The book also borrows from the war experience of Brooks' father: Mel fought in the Second World War before going on to make The Producers, Blazing Saddles et al. "In Harlem Hellfighters there's a scene of the soldiers on the boat, vomiting," his son says. "That really happened to the Hellfighters, but it also happened to my dad, as his convoy zigzagged across the north Atlantic, trying to get to Europe."

Brooks is a diligent researcher. He hired a fact-checker to maintain World War Z's assiduous realism, and spent 16 years studying the Harlem Hellfighters. The events in the graphic novel are all historical, though he did invent a handful of characters to complement the real-life heroes – since the aim of the project was not 100 per cent accuracy, but to return the Hellfighters to the public mind.

"When it's a story that no one has even heard of, any step forward is a step in the right direction," Brooks says. "There were a few things in Red Tails that were not historically accurate, but because of that movie everybody knows now who the Tuskegee Airmen were." And while he says that, on top of his writing, "Hollywood is an extra credit [which] comes second, maybe third", he admits a film would make all the difference: "If, a couple of years from now, there are billboards all over the country that say 'Harlem Hellfighters' on them, mission accomplished."

'The Harlem Hellfighters' is published by Duckworth

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments