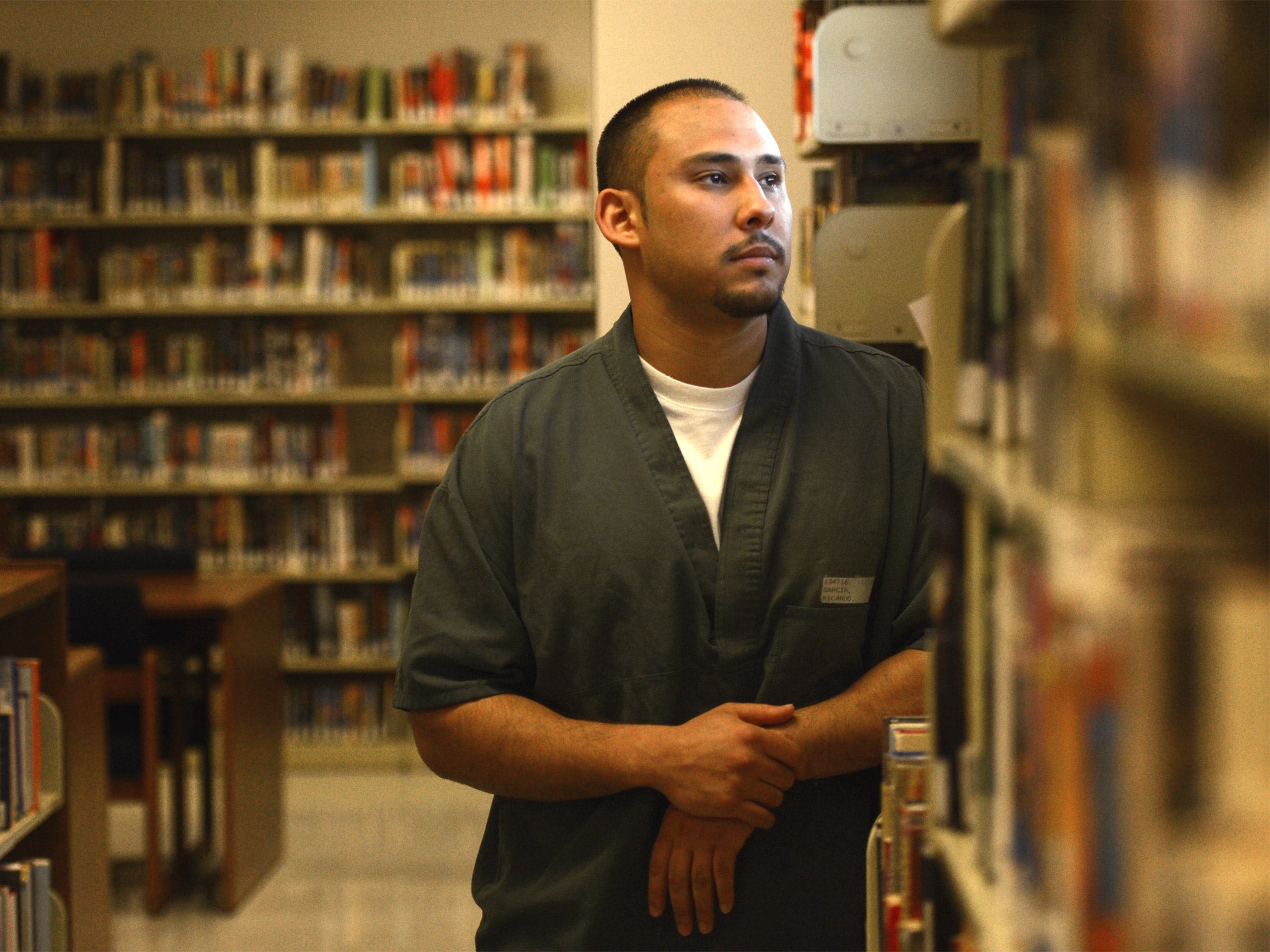

Why books are a lifeline for prisoners

Terence Blacker was on a visit to a prison to talk about the benefits of reading when he heard about the ban on books. Where better to contemplate the folly of the move?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In a hut that passes for an education centre, some prisoners were talking about books. The conversation was not of favourite authors, or what they had read recently, but of families, the future, of life outside. Relaxed and emotionally open, it was an unusual conversation for any group of men. In the confines of a prison, it was remarkable and moving.

By a quirk of timing, I was visiting two prisons in Northern Ireland to talk about books during the very week when the Justice Minister, Chris Grayling, was explaining to the world that such things should be regarded as privileges which prisoners would have to earn. Receiving books from outside will no longer be allowed. Those core nostrums of Tory values – economy, security and punishment – have been invoked.

How I wish that Mr Grayling had been present at the sessions last week at HMP Magilligan, a sprawling former barracks situated on the bleakly beautiful northern coast of County Derry, and HMP Hydebank Wood, a high-security prison in south Belfast for women and young offenders. He would have seen that, for some of those paying their debt to society, reading is not some vague form of entertainment but can be a practical lifeline, a way of changing lives – and, yes, of saving public money.

The project I saw in action is called The Big Book Share, and involves prisoners reading and recording chapters of children's books. A CD of the reading is given to their families so that children (and, in the case of some of the women prisoners, grandchildren, nephews and nieces) can listen to a bedtime story from inside. A copy of the book being read is also supplied, allowing the children to continue reading it themselves.

The eight men I met at Magilligan were mostly young- to middle-aged fathers serving short sentences. Some had been reading stories for their children, others were working on their own stories. One read a poem he had written about his family, accompanied by another inmate, finger-picking on a guitar.

It was an eye-opener. In my experience, well-meaning projects for prisons can sometimes have a whiff of do-goodery about them, but the book share was clearly having obvious and immediate effects. For a start, it was strengthening families. The men felt – and they were right – that by reading and recording bedtime stories they were doing something useful for their children and wives.

A story is neutral. Reading books to their children allows prisoners an element of normality. They can be funny or exciting or reassuring. For those moments, they are simply a parent taking a child into a storybook world at the end of the day.

The children benefited, too. One man told me that the school his nine-year-old son attended had reported that the child's emotional and reading development and his general levels of attention had improved immeasurably as result of having his father read stories to him.

In a recent letter to the Poet Laureate, Carol Ann Duffy, Chris Grayling argued that improving literacy levels, not access to literature, was the real challenge in prisons.

It is a strikingly unimaginative position. One of the prisoners at Magilligan told me that the project had forced him to overcome illiteracy, which had been one of the great problems of his life. He had learnt to read so that he could tell stories to his children.

We talked about how writing and telling stories can help put the disorder and unhappiness of life life into some sort of shape. It allows empathy for others. Our conversation was surprisingly upbeat, with the focus on the future rather than the grim present.

Back in London, there have been anguished protests from authors, with many a reference to hope, fairness, decency, to the reading of books as a general force for good. There was a protest outside Pentonville Prison. Mystifyingly, some good-hearted folks have been taking photographs of their own bookshelves, presumably as an inspiration to deprived prisoners.

If anything, Grayling's position has hardened. The public want to see prison as "a regime that is more Spartan unless you do the right thing," he has sternly pronounced. Appealing to the punishment-freak of the electorate has always been a vote-winner. Upsetting members of the liberal elite has, one suspects, been something of a bonus.

Perhaps, if the general arguments for reading are a touch wet for the Justice Minister, he might consider the practical, economic case.

Making access to books significantly more difficult is not only morally dysfunctional. It also profoundly stupid and short-sighted.

The project I saw shows that encouraging access to books can help rebuild families and encourage rehabilitation. As a result, rates of reoffending will be reduced, as will the financial and social costs involved.

The next day I was at HMP Hydebank with a group of women prisoners. Most of them were older than the men, and some were serving long sentences for serious crimes. The conversation here was more guarded. The storytelling project was at an earlier stage, but was already having an effect.

We talked about writing and reading, how books and stories could help them and their families. We listened to a recording of a prisoner reading a chapter from one of my children's books, opening and closing with a message to her son and daughter.

As with the men, songs were mentioned, too. Before lock-up at 12.30, one of them gave an unaccompanied rendition of a song written by the country star Willie Nelson and made famous by Patsy Cline. It was called "Crazy", and seemed an appropriate final note in the week that a benighted, unimaginative government argued against the lifeline of books and reading for prisoners.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments