The unseen Charles Dickens: read the excoriating essay on Victorian poverty that no-one knew he had written

The essay had previously been attributed to one Joseph Parkinson

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

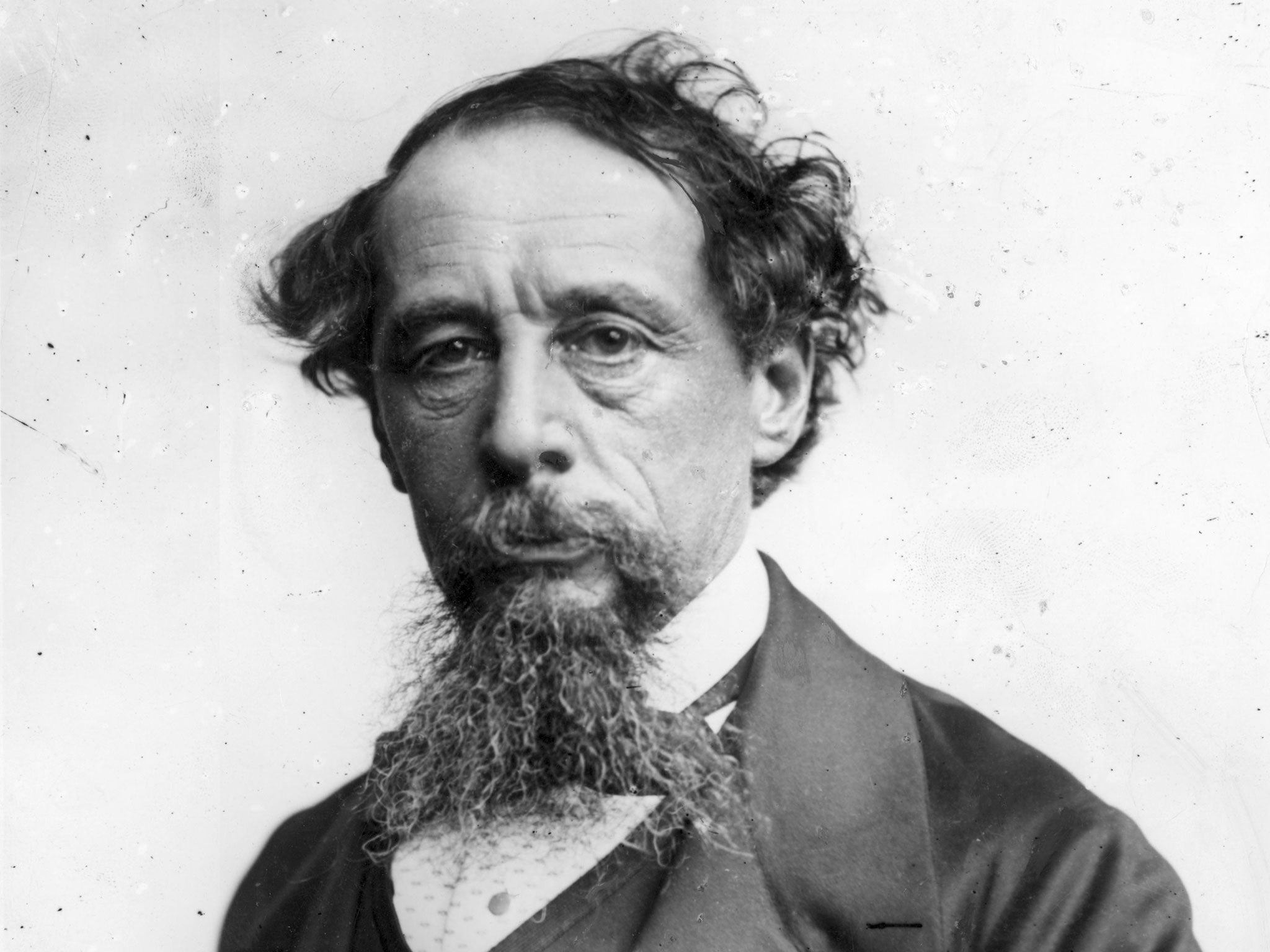

Your support makes all the difference.As The Independent revealed on Monday, a bound collection of the 19th century magazine ‘All the Year Round’, annotated by its editor Charles Dickens, has yielded the names of the articles’ anonymous authors; among them Lewis Carroll, Elizabeth Gaskell and Dickens himself.

One of the most spectacular essays – an attack on a complacent establishment that could tolerate the appalling state of poor relief – had previously been attributed to one Joseph Parkinson, and presumed to be only a commission from the great man of letters. But from the newly studied margin notes, it now seems that Dickens not only supplied the idea but was chief author of the polemic. Below, we publish the piece - originally entitled ‘What Is Sensational?’ – which remains a great example of passionate reporting; still relevant, still an inspiration to anyone who sees their role as giving a voice to those who cannot be heard.

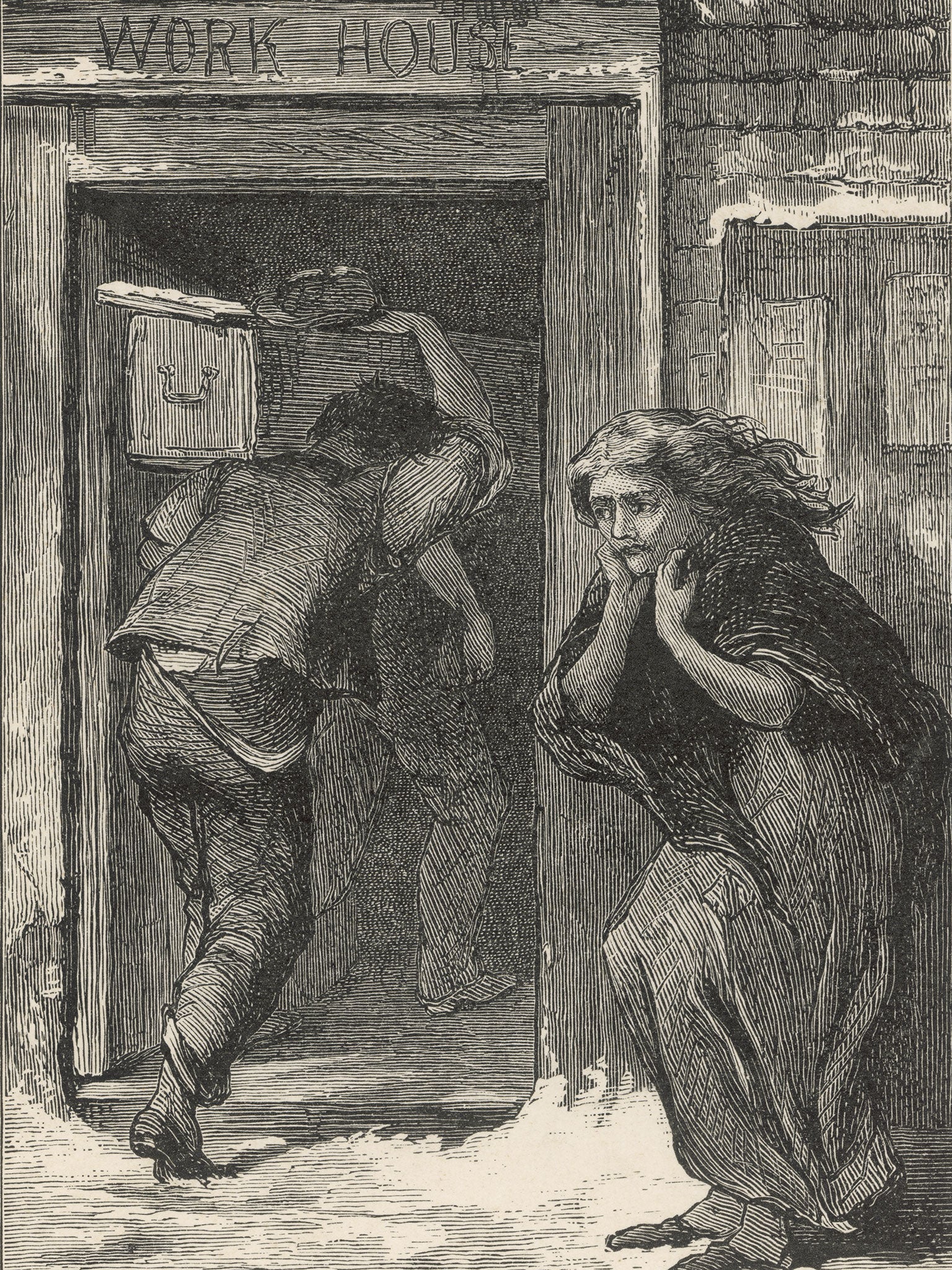

The essay came after a number of scandals involving conditions in the workhouses hit the headlines during the 1860s. It uses a series of rhetorical questions to highlight the abuse of the poor and the failures of those found wanting in their duty of care. The title plays on the then current vogue for 'sensational' literature, most notably exemplified by Mrs Braddon and Wilkie Collins. For Dickens it is not fiction that is sensational but the appalling facts about how the poor were neglected and mistreated.

In his opening argument Dickens addresses Gathorne Hardy, then President of the Poor Law Board, who argued that the press has sensationalised the deaths of two paupers - Timothy Daly and Richard Gibson – “murdered” by the gross neglect they suffered in workhouse hospitals in 1864 and 1865. The incidents caused a national outcry, and led to a campaign by Florence Nightingale for a major upheaval of the workhouse nursing system.

By 1867, Gathorne Hardy would be drafting a new poor law bill to remedy the situation in London’s workhouses, leading to the creation of separate hospitals and a fund to finance the costs of all drugs, medical appliances and the salaries of all poor relief officers.

What Is Sensational?

By Charles Dickens

The Right Honourable Mr Gathorne Hardy, the President of the Poor Law Board, has a grievance. The newspapers have, he says, written “sensationally” upon workhouse mismanagement, and an interest “wholly disproportionate to the circumstances” has been roused in the public mind. Further, lest any public writer should misunderstand his meaning, he is kind enough to particularise the cases to which sensation writing has been applied.

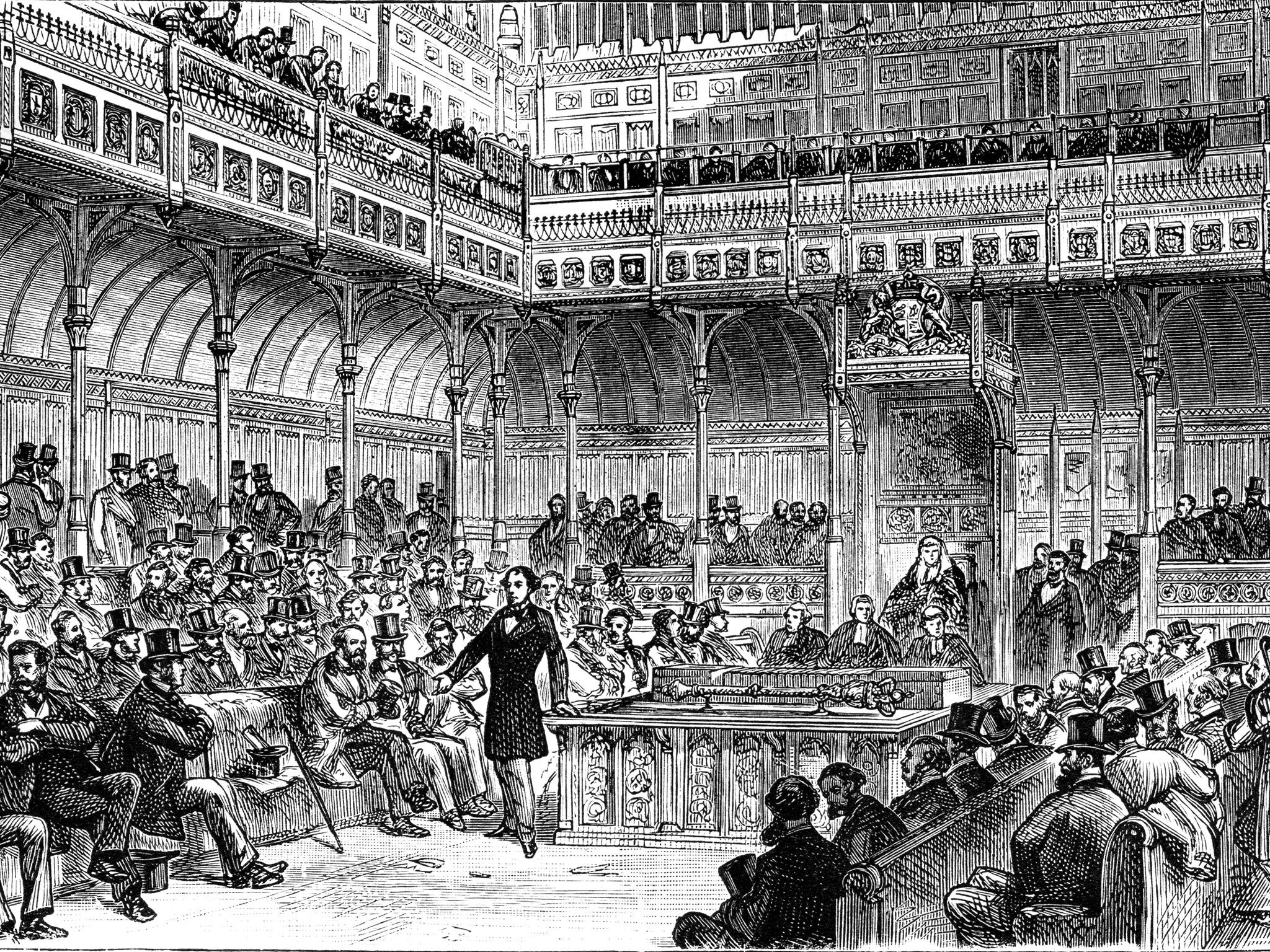

These were the condition of the Strand Union workhouse, and the deaths of the paupers Daly and Gibson. It is a noble and instructive sight to look down upon from our snug perch in the House of Commons while this genial remark is made. Opposition and government benches both full; legislators smugly quiet, attentive, and approving; while our orator, who is tediously fluent, well dressed, and self-complacent, pours forth his shameless aspersions against those who have borne disinterested testimony to the truth. Paid by the public to protect the Poor, the official representative of a costly system under which paupers starve and die can find nothing more germane to the subject of poor law reform than abuse of those who have performed the real work of his department, and but for whom, it and its salaried servants, parasites, and admirers would have continued with folded hands and brazen front to murmur, “All is well.” During the celebrated Chelsea inquiry into Crimean mismanagement, a true humorist and draughtsman, now no more, gave us a sketch of “The witness who ought to have been examined”, in the shape of the skeleton of one of the hundreds of horses dead of starvation.

But that the heartless perversity which can sneer at human suffering as sensational would not be convinced though one rose from the dead, we might well wish that the two murdered paupers, Daly and Gibson, could be brought from their graves to bear testimony against their accuser and his accomplices. Mr Hardy proclaims himself an accessory after the fact by his audacious attack on witnesses not to be suborned, and he is himself criminal in his miserable palliation of crime. “Wholly disproportionate to the circumstances,” smiles this Christian statesman, with a propitiatory wave of the hand; while well clad, well fed, clean, comfortable, prosperous legislators smile back assent, and no man says them nay.

Yet professional philanthropists, platform orators, great religious lights, men well known at Exeter Hall, and without whose names no charitable subscription-list is complete, can be seen from our point of observation here, placidly beating time to Mr Hardy’s verbose cadences, and murmuring to each other afterwards that his performance has been very creditable indeed.

The tu quoque line of argument is to be deprecated, but the daring of the arch-mediocrity below us suggests the question, what would a sensation[al] poor law president be like ? Suppose a man to succeed to office when public opinion has insisted upon reform; suppose a prime minister to herald him with a bombastic flourish as “the fittest man in the Queen’s dominions” for his onerous charge; suppose the man himself to assure the House of Commons that all previous abuses have been due to the mismanagement and indifference of his predecessor; suppose the same man to purchase the cheap cheers of his fellow- legislators by braggart promises of efficient control and personal sacrifice; and suppose him to conveniently ignore his own statements, and, while filching the labours of others, to throw stones at them from the convenient shelter of parliamentary place — would this be sensational?

Suppose the nation to be so outraged by the abuses and cruelties tacitly sanctioned by one notorious department and its officers, that some show of justice and humanity to paupers is found necessary to prolong the life of an unpopular ministry — is the use of charity and decency as political counters, sensational? Suppose a servant of the State to be bold as a lion in his pledges to the public, and as meek as a sucking dove in his performances with guardians; suppose him to be outwardly rigid and privately compromising — is this sensational? Suppose he, or an officer under his direction, to preface public investigations by private interviews with the people accused, wherein friendly hints are given how damaging evidence may be suppressed; suppose him to have other investigations conducted with closed doors, and to cause others again to be so craftily managed that the evidence is published and the verdict resolutely kept back — is this sensational? Suppose a pinchbeck popularity to be earned by the adoption of other men’s ideas and a wholesale renunciation of one’s own — is this sensational? Suppose underhand relations are endeavoured to be established between a public body and its critics, and sops to be proffered to Cerberus so deftly that a stern front and frowning brow is successfully maintained even while coaxings, fondlings, and tit-bits are being offered — is this sensational? To ally oneself with pitiful intriguers; to purchase hirelings who, having played fetch and carry to one set of masters, are ready to transfer their venal and shameful services to the highest bidder with a cheerful unscrupulousness that such light o’ loves only know — is this sensational? Is it sensational to pander, palter, truckle, and deceive; to hush up cruelty and brutality to the helpless, frauds on the ratepayers, and dishonesty to the poor? Is it sensational to bid for political support by throwing the judicial mantle over parochial misdeeds? Is it sensational to make active sympathy with suffering a matter for punishment; and selfish indifference the key to favour and reward? Is it sensational to blow hot and cold, to reprove bluffly, and cringe servilely; to degrade a Christian’s duty into a charlatan’s trick; to abet the oppressor, and use the giant’s strength against the oppressed? Which was sensational, the dynasty converting “the negation of God into a system of government” or the statesman who called down the indignation of Europe on its atrocities ? Let Mr Hardy give us benighted public writers information on such points as these.

Sensational writing in the newspapers! Why, the right honourable gentleman is surely contributing sensational writing for tomorrow’s issue by the yard. That he and the party of obstruction should eat the leek by meekly appropriating the views and arguments used by their opponents when such measures as the Houseless Poor Act and the Union Chargeability Bill were proposed and carried in their teeth; that the love of place should awaken a sense of justice; that those “carrying the bag” should have been whipped into even a semblance of caring for the poor, is surely sensational enough for common readers. It is as the public defender of the system, and the censor of those public witnesses whose evidence is not hired, rather than as the man responsible for the particular acts alluded to, that Mr Hardy stands self-accused; and such writers as respect themselves and their vocation are not likely to forget his words. Running with the hare and hunting with the hounds is not always a successful policy, and it is useful to observe how the measure introduced is a practical refutation to the charge made; how every useful clause in it can be directly traced to the influence of independent comment and suggestion; how the tacit admissions of the speaker are damnatory to the expensive sham he represents. The flippancy which would propitiate the guardian class at the expense not merely of humanity but honesty, is inexpressibly shocking; and with this before one, the bill itself, useful as many of its provisions are, seems like a bribe thrown half contemptuously to an irritated and long-suffering public, rather than a conscientiously devised remedy for flagrant abuse.

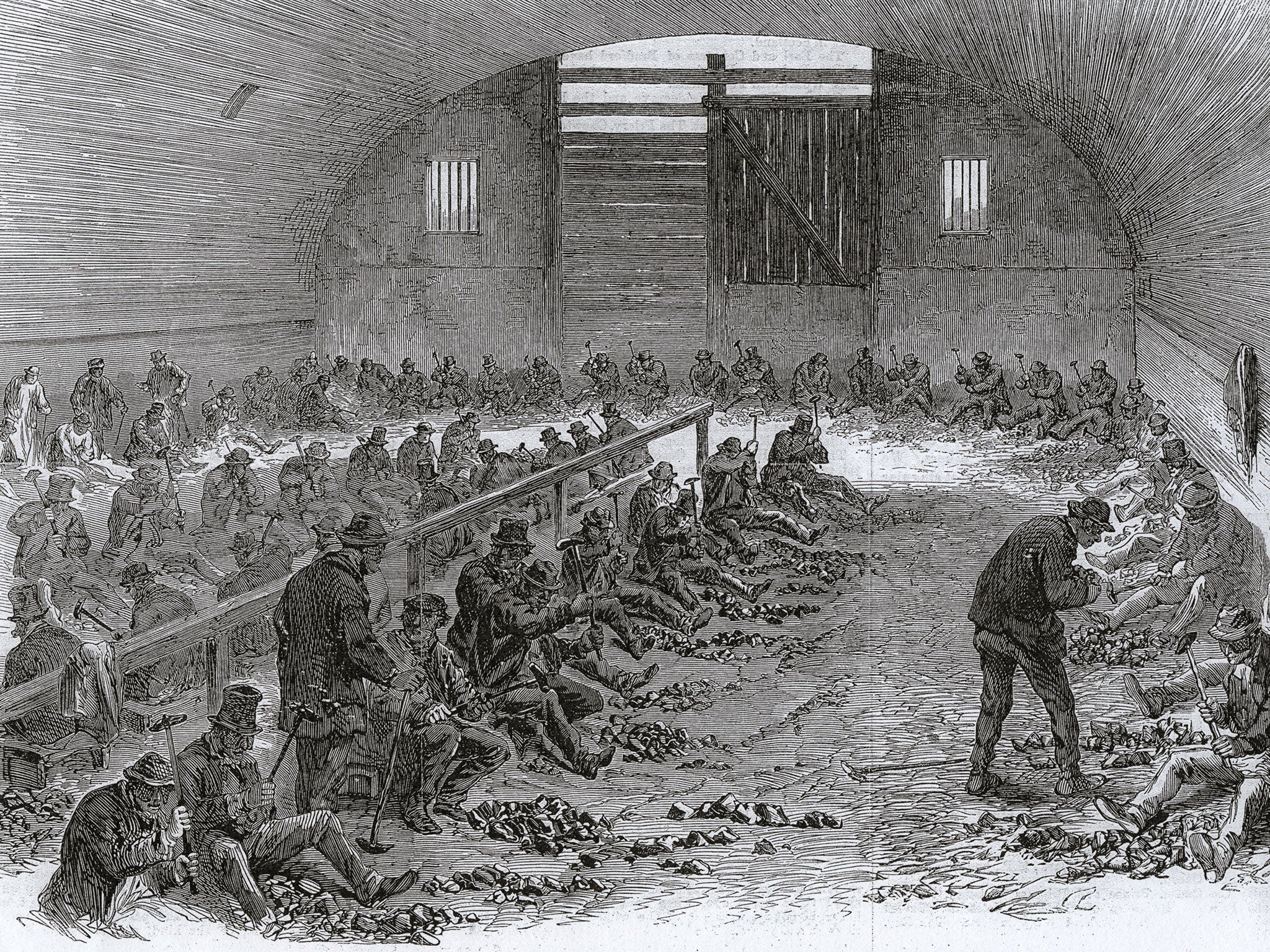

Let us accept Mr Gathorne Hardy’s challenge, and by recapitulating the facts he takes exception to, grope darkly for his definition of the word “sensational.” Selecting the workhouse he quotes as an example, what do we find its discipline and internal arrangements to have been? Carpet-beating carried on as a trade among its infirmary wards; the dust and flue settling upon the sick and dying, aggravating their sufferings and hastening their end; a broken-down potboy employed as nurse, who trembled from sheer debility when spoken to; patients unable to move in bed without assistance, and help refused them by the guardians in defiance of the entreaties of their own medical officer; the beer, wine, and spirits provided to keep body and soul together habitually stolen from the wretched patients by pauper wardsmen and nurses, an emporium for their sale, known as “the Brimstone Hotel,” flourishing within the workhouse walls; and a standing proposal to reduce the doctor’s salary brought forward whenever he made an effort for reform. These were the proved facts.

The wretched jocularities of human brutes as to mesenteric disease being “something to eat”; the ironical suggestions for “armchairs and drawing-rooms for paupers,” both occurred at the official inquiry here; and that killing consumptive paupers with carpet-dust has been discontinued, and that the nursing and discipline have been partially amended, is due, not to our Poor Law Board or its officers, but to independent inquiry and the stern comments it evoked. It fortunately happens that, since these comments were made, a return from the Poor Law Board to the House of Commons, dated “7th August, 1866,” and signed “H Fleming, Secretary,” has been obtained. Let us ask Mr Hardy, is this a sensational document? Are the following statements by Dr Rogers, the medical officer of the union which was sympathised with by the responsible head of the Poor Law Board as the object of attacks in the newspapers — are these sensational? Speaking of the Strand Union workhouse, Dr. Rogers writes: “In the first summer following my appointment, an outbreak of fever took place, owing to excessive overcrowding and deficient accommodation. . . . The ward then used for the reception of persons admitted on nightly orders, called ‘Pug’s Hole’ by the inmates, was a cellar (without area), and of the most objectionable kind, and the hotbed from which fever was largely propagated. . . . .

Having repeatedly noticed that the suckling women became consumptive, or suffered from diseases of an exhaustive character, and that many of their children died, I found, on inquiry, that the dietary of the lying-in ward (over which I had then no control, and was not supposed to enter without the request of the master or midwife) was very insufficient, as it consisted only of gruel for nine days, and that when discharged to the nursery they went at once on the common diet of the house. . . . .

In the year 1862, a severe outbreak of fever took place in the building, due solely to overcrowding ; twenty-five cases occurred in quick succession. . . . . On or about this time I suggested to the visiting committee an alteration of the dead-house, the grating etc, from which opened beneath the windows of the women’s infirm wards. . . . . From this grating foul emanations from the dead frequently arose and filled the wards, and in the summer large blue- flies flew in and out of them from the dead- house. . . . . In 1864, overcrowding having again taken place. . . . . a malignant fever broke out in the house. . . . . In May, 1865, the Poor Law Board addressed you (the Strand Union guardians) on the subject of pauper nurses, and strongly advised you to engage paid and responsible persons. . . . . you, however, engaged one, and by the terms of the advertisement limited her attendance to those patients only who were in the two sick wards, amounting to about forty persons, and yet the house contained, as you are aware by the weekly returns, four hundred sick, aged, or permanently disabled persons.” “When Belsham, the pauper nurse, was removed at my instance, for robbing the sick, the master, in consequence of a suggestion by me, undertook to bring the question forward, and applied for paid assistance, as the circumstances were such as admitted of no delay. The total refusal, as he informed me, of the visiting committee, and the recommendation of one of the guardians to employ a broken-down potboy whose antecedents he so well knew, was a proof, coupled with what I have above referred to, that it would be a mere waste of time to make any further communication to your board on the subject.

“At the early part of the year 1864, the late Mr Jeffreys moved that my salary should be increased. I waited upon him, and others who I knew were favourable to me, and urged them to get your board to provide medicines instead, as I wished to establish the principle that in such a large house as the Strand, all the drugs should be found at the cost of the ratepayers, thereby evincing that I had some other feeling in the matter save that of getting a little more money. Your board assented to the proposition tion, but limited my outlay on this head to £30 only in the year.” Finally, after recounting his efforts to have those abuses remedied, Dr Rogers’s testimony thus concludes: “I have regretted many times, and deeply, that these efforts, instead of receiving the cordial sympathies and assistance of (the guardians), have entailed upon me much annoyance, hostility, and undeserved insult.” Was it sensational, let us ask again, for an inspector from the Poor Law Board to conduct an inquiry into the malpractices of this shameful workhouse, as if he held a brief for the guardians; and to attempt to crush their medical officer as one of the troublesome fellows clamouring for reform? Passing to published records of the death of the wretched Timothy Daly, let us see what is sensational here. We all know that The dog, to gain his private ends, Went mad and bit the man and Mr Hardy would, doubtless, tell us that Daly died obstinately and sensationally for malicious purposes of his own, and with an eye to posthumous celebrity. This poor man was found at his lodgings, in want of the common necessaries of life; and though he frequently implored the parish doctor to procure him food and nutriment, the latter omitted to do so, on the supposition that Daly’s pride would be wounded at receiving them from parochial sources. He had nothing but a little milk and gruel for two or three days, and was so weakened when it was decided to take him to the workhouse, that stimulants were prescribed. It being nobody’s business to give them to him, he had, instead, an aperient, a sedative, and a syrup ; and arrived at the Holborn Union workhouse, well physicked, unfed, and half fainting from debility. Here, he had neither food nor medical advice until the next day, but was placed in a hot bath, because a pauper nurse thought him “by no means clean”; he became (not unnaturally) worse in the night, and his condition was pronounced dangerous when the doctor saw him some hours afterwards. Bed-sores supervened, and were not discovered by the doctor until that vague period, “three or four days,” had elapsed, so a pauper nurse bestrewed them with fullers’ earth, to the miserable pauper’s injury.

He was placed on a bed several inches too short for hi, and, after some weeks of anguish and neglect, the poor wretch had so strong a conviction that he was being killed by ill-treatment, that he preferred dying of starvation and disease outside, and had himself moved away.

Subsequently he was admitted to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, where he died the day after his admission, of “ exhaustion” arising from workhouse bed-sores and neglect.

The circumstances of this death were sensationally held to be a conclusive testimony to the uncertainty and irresponsibility attending the administration of our parochial system; and it was sensationally urged that, although Daly was completely within the circle of that system, he died for want of careful watching and suitable food.

Richard Gibson perished in St Giles’s workhouse, encrusted with corruption and filth, covered with vermin, and without proper nourishment or medical attendance. After protracted suffering, he was mercifully killed off with gin, surreptitiously administered by a drunken pauper nurse. The medical officer had passed the sick man’s bed, daily, without asking after his condition, or knowing how his disease progressed, or whether his bed-clothes were foul or clean; and a parochial coffin would have concealed Gibson’s sufferings and wrongs without boards, Bumbles, or the public, being the wiser, but for an audacious pauper named Magee, who wrote to the sitting magistrate at Bow-street, and so caused a “sensational “ inquiry, sensational reports, and a sensational shock of horror and indignation, wherever men and women — not belonging to the Poor Law Board — could read, and think, and feel.

Let us ask again what does Mr Gathorne Hardy mean by “sensational”? Is it sensational to tell the truth? Is it sensational to call public attention to a noteworthy example of a costly board existing under false pretences, and showing mankind how not to do it? Is it sensational to be poor, abject, wretched, dying? Is it sensational in a public officer, when he has nothing to say for his department, meanly to shelter himself under the miserable slang of the hour? Is the commonest humanity, the narrowest charity, sensational? What is Mr Hardy’s opinion of the New Testament? A sensational performance surely ! The good Samaritan ? A highly sensational character.

The twelve Apostles? What a sensational dozen ! Their Divine Master? Inconveniently and notably sensational! There was a time when men symbolically expressed their names in what was called a “rebus.” Perhaps the newest sensational effect is for a public servant to do this in a new way, and thus Mr Hardy sensationally exhibits himself as the most hardy man alive. The House of Commons may be all that Mr Disraeli says it is, or it may be the different thing that most other men know it to be ; but in either case it is surely remarkable that there is no man in it to put a notice on the paper “to ask the Right Honourable the Chief of the Bumbles for his definition of sensational”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments