What can a landmark rap anthology tell us about the links between the poetry of the street and the poetry of the page?

The notorious reputation of American rap as synonymous with the music of crotch-grabbing, booty-shaking, gangsta-glorifying, blinged-out machismo is both endorsed and challenged by a groundbreaking anthology. Featuring over three hundred rap lyrics written between 1978 and 2010, The Anthology of Rap (edited by Adam Bradley and Andrew DuBois; Yale, £19.99, 867pp) makes the history, development and variety of the genre plain to see in vivid detail. But the editors invite us to consider their anthology as something more than a collection of lyrics, spoken word or slam poetry. They write that this is rather "a collection of rap's best poetry".

In a powerful, sword-wielding introduction that seeks to slay all counter-arguments, they present a persuasive case for a serious re-evaluation of the "poetry of hip hop culture": a poetry utilising standard poetic devices of rhythm and rhyme, figurative language, enjambment, alliteration and assonance. To accusations that rap is doggerel, they argue that a lot of if it isn't, comparing Vanilla Ice's rudimentary, "Will it ever stop? Yo, I don't know/ Turn off the lights and I'll glow", with Rakim's scintillating, "Dead in the middle of Little Italy little did we know/ That we riddled some middlemen who didn't do diddly".

Rap's controversial reputation for violence, misogyny and homophobia isn't sidestepped, either. Including these themes is, they say, a way to confront them rather than "simply pretending they aren't there". And it ensures that, where the exceptions occur, their courage is even more remarkable – as in the gay Deep Dickollective, who describe themselves in their "For Coloured Boys" rap as "homo revolutionary males".

For those who think all rap sounds the same, this book shows it is anything but. Four eras of the genre are represented: the Old School, the Golden Age, Rap Goes Mainstream and New Millennium Rap. Starting with rap's underground origins in the New York ghettoes of the mid-Seventies and the pioneering work of a Jamaican teenage immigrant, DJ Kool Herc, we journey to the worldwide celebrity of the hip hop zillionaires of today - Jay-Z, Diddy, 50 Cent, Eminem.

So how do these lyrics, each chosen for their poetic interest, excellence or significance, stand up to literary scrutiny when stripped of music, background beats and performance? The initial signs aren't good. Early rap's partying spirit is poetically and thematically banal: "Come on and let's go to work/ Let's do it, let's do it/ Said the disco lights and the boogie nights/ Are really here to stay/ Sexy mamas and fancy papas/ Always want to play" (DJ Hollywood). Its attempts at gravitas are deeply unconvincing: "The media is telling lies/ Devil takin off his disguise/They're killing us in the street/ While we pay more for food that's cheap" (Brother D with Collective Effort).

The cheap rhymes and braggadocio rooted in competitive "battle rapping" often makes it resemble the worst kind of performance poetry: "Now I rule the world and now I'm on top/ And I'm rollin with folks that could never be stopped/ And I'm here to let you know this is where I belong/ And to you sucker MCs, this is my song" (Kurtis Blow). A high drivel content runs through many early lyrics, rescued sometimes by wit: "Jack and Jill went up the hill/ To have a little fun/ But stupid Jill forgot the pill/ And now they have a son" (Lady B). Brevity rarely features – many of the lyrics go on for pages. Haiku rap, anyone?

By the mid-Eighties, rap became increasingly political with NWA, De La Soul and Public Enemy, whose anti-racist anthem "Fight The Power" is thrilling in performance but looks amateurish on the page: "Elvis was a hero most/ But he never meant shit to me – you see/ Straight out racist, the sucker was simple and plain". The clever internal rhymes, syncopated rhythms and wider frame of reference of Big Daddy Kane make him stand out.

Rap next evolved into the "suck-my-dick, bitch" culture many still exclusively associate it with – and can't forgive it for. Young, angry, black men from the ghetto elevated themselves with a pumped-up swagger and compulsion to degrade and insult women. Queen Latifah was one of the few women rappers to be heard and, oh boy, did she answer back. As her furious, feminist and quite frankly fantastic "U.N.I.T.Y" puts it, "Who you calling a bitch?"

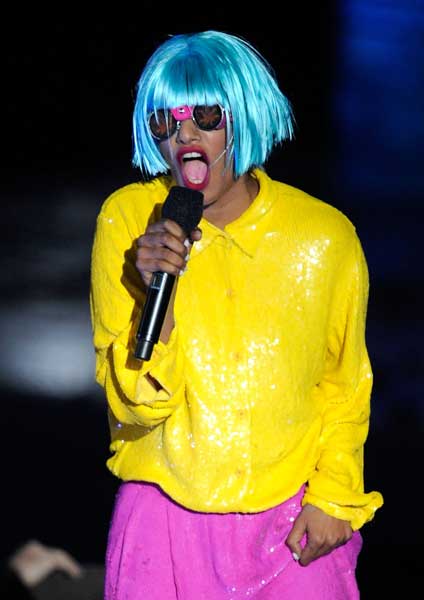

Permission issues prevent it being included in the anthology – a real shame. Catch it on YouTube instead. Other women featured also reveal plenty of strength - Roxanne Shante who wrote "Independent Women", M.I.A, Lauryn Hill. At the opposite end of the spectrum is the controversial, hypersexual Lil' Kim whose "Queen Bitch" pronounces, "I am a diamond cluster hustler/ Queen bitch, supreme bitch, killa nigga for my nigga/ By any means bitch, murder scene bitch".

Many of the rappers' lyrics expose limited diction and imagination but Canibus's metaphorical brilliance sets him apart: "The Polar Manitoba's melted by lava/ A team of ER doctors climb aboard my chopper/ My skull is a submarine hull, I empty the ballast tanks/ I could smell the shit from the seagulls/ My mind dives deep beneath yours, Poseidon Trident/ Seahorse bubbles form,/ I scream with extreme force". In fact, any lyrics that don't use the N or M words and draw on wider cultural references stand out, such as the The Wu Tang Clan's "Triumph": 'I bomb atomically, Socrates philosophies/ And hypotheses can't define how I be droppin these/Mockeries, lyrically perform armed robbery".

Then, of course, there's Eminem, who broke through as the potty-mouthed but pretty blond face of rap and is its best-selling artist of the past decade. His triple-persona lyrics (Eminem, Slim Shady, Marshall Mathers) are tightly-wrought, angst-ridden, narrative-driven, original. Like the "real Slim Shady", they stand up.

The anger and energy that drives rap gives it a lawless, visceral power. It is the predominant means of creative expression for young, working-class African-American males, and to a lesser degree women. As rapper MC Lyte says, "When I was young...I was like, how else can a young black girl of my age be heard all around the world. I gotta rap". The form is intrinsically outspoken, speaking out, to and against, which puts it at odds with the poetry of implication, obliquity and nuance. The best raps show raw power, linguistic ingenuity and wit. The worst are cliché-riddled, foul-mouthed rants.

But rap is a multi-billion-pound global industry and its mix of spoken word and music reaches across boundaries. At worst its cultural and sociological influence is pernicious, but it is undoubtedly a phenomenon. Unlike almost every other kind of "poetry", it reaches a mass audience.

Poetry publishing in Britain was and remains overwhelmingly white. Back in the Nineties, the language, rhythms, tropes and freedom American rap offered inspired a new generation of young black poets to find their voices and deliver their own brand of lyric creativity. The most skilful made the transition to publication, such as Patience Agbabi, whose individualistic poetry is as dynamic in performance as on the page. Others found that populist, personality-based performance poetry was no substitute for poetic complexity and craft. Further back in the Eighties, Linton Kwesi Johnson was a pioneer of dub poetry - spoken word drenched in the vernacular and beats of reggae. Now published by Penguin Modern Classics, his poetry is accepted on its own terms.

Placing rap lyrics so firmly in the poetry camp inevitably does rap a disservice. It is a performance genre and what is weak on the page - awkward metrical syntax, sloppy rhyme, corny lyrics, rambling verses - can be camouflaged on stage by music and delivery. Yet this anthology achieves its purpose in drawing attention to the themes and techniques of rap throughout its historical development. And with nothing between us and the words, we can see clearly what is really being said.

The editors write, "Far from denying rap's value as music... readers stand to gain a renewed appreciation for by considering the poetry of its lyrics. To study rap as poetry is to pause in contemplation before returning to the beats and rhymes of the music itself." They're right. And if dipping into it doesn't cause you to go and listen to some, then surely nothing will.

Bernardine Evaristo is the author of 'Lara' (Bloodaxe Books) and a judge for this year's TS Eliot Prize for poetry, which will be announced on 24 January

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments