Victoria Mas on The Mad Women’s Ball: ‘My book is a fiction... but terrible things really happened to women in Paris 200 years ago’

The author talks to Helen Brown about her prize-winning debut novel, the mistreatment of ‘hysterics’, French and anglophone feminism, and growing up the daughter of a pop star

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

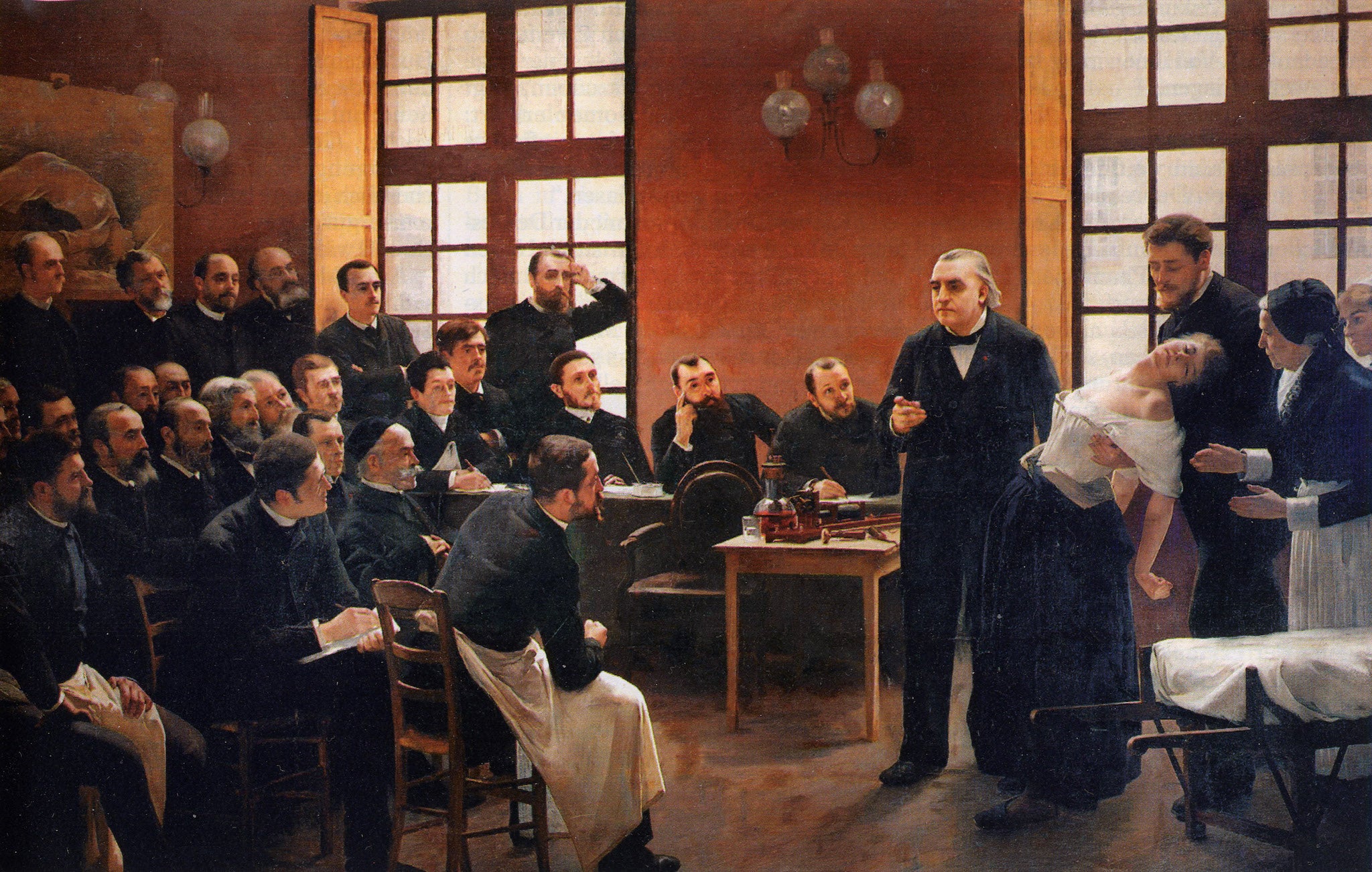

Your support makes all the difference.In the opening pages of Victoria Mas’s debut novel, The Mad Women’s Ball, a 16-year-old girl is hypnotised by a 65-year-old man. “Shoulders back, bosom forward, head held high,” the girl walks proudly into a lecture theatre at the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital in Paris to perform her hysteria for the students of her “master”, Dr Jean-Martin Charcot. The assembled men lean forward as Charcot swings his pendulum before the girl’s motionless blue eyes and she tumbles to the floor. Pressing her head and feet against the bare boards, she creates a perfect arc with her back as “the expressions on her face veer from ecstasy to pain, her contortions punctuated by guttural breaths”.

“My book is a fiction,” says Mas, “but it is based on events that really happened in 19th-century Paris. Terrible things that really happened to many women in the Salpêtrière 200 years ago, when the very thin line between medical treatment and voyeurism was blurred.”

On a video link from her home in Paris, the shy, 31-year-old daughter of Eighties French electropop star Jeanne Mas tells me she only learnt about the “heavy history” of France’s largest hospital in 2017. “I dropped a friend at A&E and realised the place was like a small town, with its own streets, park and chapel. I was inspired to read up on the history, and that’s when I learned about Jean-Martin Charcot and the many women who were locked up there in his care, often just because they were strong-willed or inconvenient. They were not just prisoners but also the subject of so much fascination. The elite of Paris would come to see Charcot’s lectures. Once a year there was an annual ball at the Salpêtrière with the cream of society invited to come and view the mad women, all dressed up like the stars of a freak show. Photographs of the women experiencing ‘hysterical fits’ were also popular. Those pictures are still fascinating. Their faces haunted me until I had to write about them.”

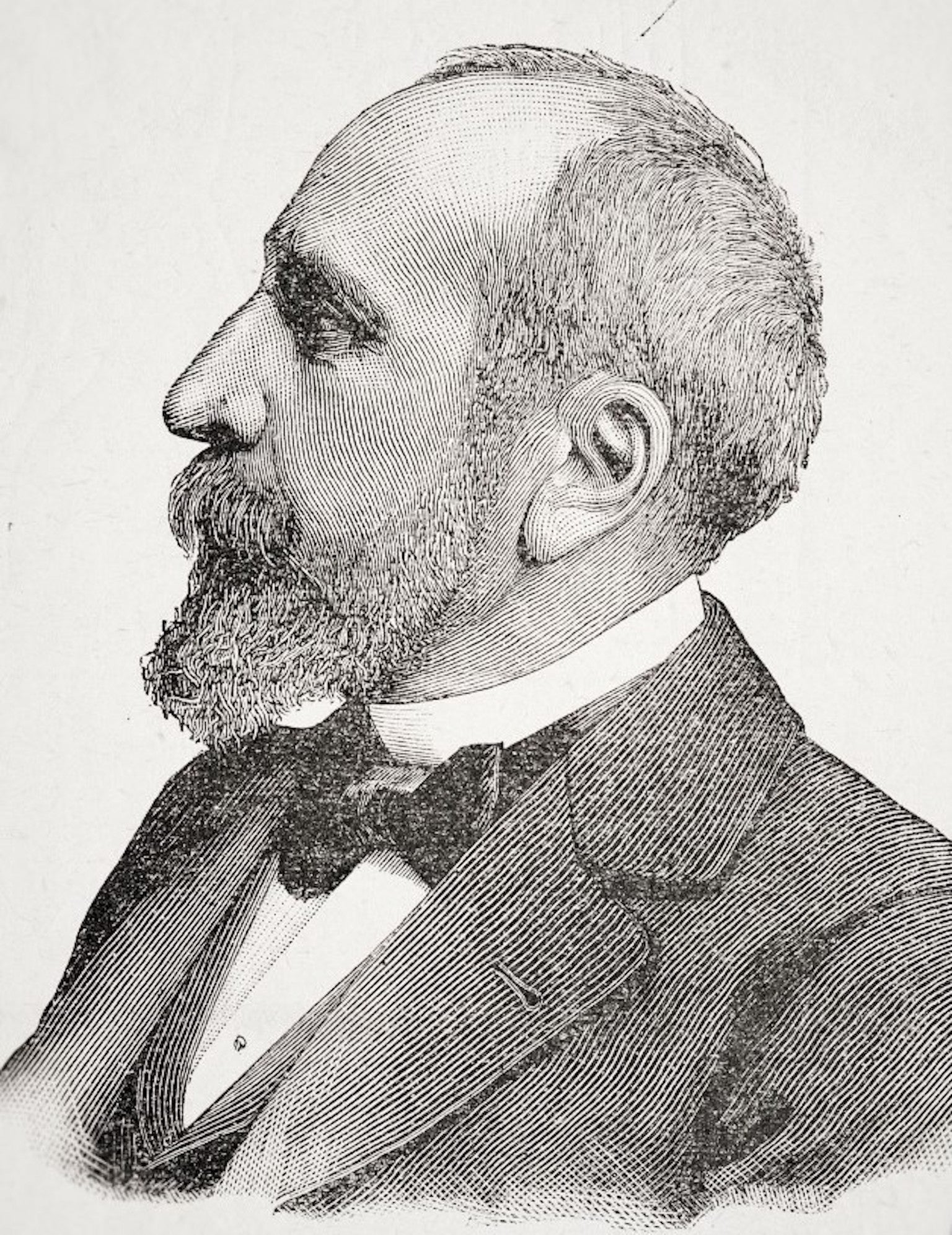

Nicknamed the “Napoleon of neuroses”, Charcot was a pioneering French neurologist who lived from 1825-1893. The neurology clinic he opened at the Salpêtrière in 1882 was the first of its kind in Europe. There he was the first doctor to describe multiple sclerosis among a host of other conditions. But he is best remembered for his work with female “hysterics”, whom he treated with hypnosis, cauterisation of the cervix and compression of the ovaries, both with the hands and – over many hours – with a kind of medical vice.

“Back then they were on the brink of the birth of psychology,” says Mas. “They could only explain emotional problems through the body at that time. They focused on the women’s genitals. They were on the brink of realising that trauma and social deprivation had this effect on the mind. They were just about to start listening.”

The word hysteria comes from the Greek word for the uterus (hystera), which the doctors of ancient Egypt and Greece believed “wandered” around the female body, causing behavioural abnormalities. Between the Fifth and 13th centuries, European Christians decided that the behaviours associated with what was called hysteria were also a consequence of “sin”. It wasn’t until the final years of Charcot’s life that Sigmund Freud (who attended Charcot’s lectures) theorised that “hysteria” stemmed from childhood sexual abuse or repression.

Charcot’s most famous patient was the beautiful Louise Augustine Gleizes, who was just 14 years old when she was admitted to the Salpêtrière in 1875. In his notes on Gleizes, anatomist Paul Richer recorded that, aged 13, Gleizes had been placed in the care of a man who had threatened her with a razor and raped her. When she was bleeding and – unsurprisingly – felt “pain in the genitals and was unable to walk” the following day, Gleizes was diagnosed with hysteria.

Because Gleizes (with her alluring porcelain-white skin and lustrous dark hair) had a theatrical bent, she was regularly wheeled out to perform at Charcot’s lectures. Because, as Richer noted, “the camera loves her”, she was also one of the hospital’s most photographed inmates.

It’s interesting that Charcot’s public performances occurred in the wake of the revolution of 1848. The successive revolutions since 1789 had swept Catholicism from the hearts and minds of Paris. Science was the new religion, and believers found their new creed echoing old rituals. Mas says: “From our perspective, Charcot looks a little like a cult leader. He had so many disciples. His patients and his students were in awe of him. He would bring out these women for his congregation and perform something like an exorcism.”

Mas notes that although Eugenie – the heroine of her novel – is a middle-class girl, most inmates in Charcot’s ward were “poor girls, often illiterate, which is why it was so hard for me to find records of them. I was lucky to read two accounts. One was from a woman who was put into another psychiatric hospital. She was a pianist from an upper-class family, and she was locked away by her stepbrother because he did not want to share his inheritance with her. She was very vocal about abusive behaviour during her confinement. The most famous account from the Salpêtrière is from Jane Avril, who was very grateful for how she was kept safe in the hospital after being violently abused by her mother. She learned to express herself through dance at the hospital and went on to be one of the most famous dancers at the Moulin Rouge – she was drawn by Picasso and Toulouse-Lautrec.”

Mas is such a reticent speaker I’d never guess she was a pop singer’s child. Unlike many Eighties celebrities, Mas says, her mother “always had total creative control over her music, her looks and music videos”. Jeanne Mas – who began her music career as a punk – was also one of the first French pop singers to write about domestic violence. Today the still-glamorous Jeanne lives in the US, where she continues to make music and enjoy press attention.

But, after spending eight years in the US with her mother and younger brother, Victoria returned to France to study for an MA in literature at the Sorbonne and has stayed “because I missed the streets, the language…” America was not such a great fit, she laughs, “for an introvert”.

Born in 1987 (the year after her mother had her biggest hit with the single “En Rouge et Noir”) she spent her childhood “mostly reading in the garden” in the small village of Rognes in the south of France. Her father, now a private tutor, helped her to hone her writing skills and was very strict about using correct grammar.

As a young child she remembers standing backstage, “right behind the curtain, and feeling the crowd energy: the applause, the singing along, the cheers”. When attending concerts in the usual manner, though, she noticed that “the energy in the audience doesn’t equal the energy performers feel on stage. They are the direct subject of thousands of people who love their music and are thrilled to see them on stage. It surely must be one of the most intense experiences.”

But little Victoria had no desire to be the object of all that attention. At 17 she began reading Guy de Maupassant and Marguerite Duras and realised she wanted to create her own stories behind the curtain. “I was sucked in by their writing, but I was also fascinated by the romance of their lives as writers. I was drawn to the solitude. To the idea of a typewriter with an ocean view…”

Mas says it took her a long time to find her voice as a writer. “I tried autofiction [which makes fiction of autobiography] and lost myself in it. I worked on scripts for small films in America. I did all kinds of freelance jobs, translating and typing. It was only when I began to write about other people that I was freed up. Imagining the lives of the women in the Salpêtrière made a beautiful sense to me.”

Mas wrote while gazing at the old photographs, and “driven by curiosity. The need to understand. We wonder: can a person’s problems be visible? Or not? What can the photographs tell us?”

The more she studied those faces, the more she felt the strength of modern comparisons. When I talk of the public fascination with the breakdowns of celebrities such as Britney Spears (who, like Mas’s subjects, felt public outbursts were her only way of rebelling against unbreakable male control) she nods.

“Voyeurism is still with us,” she says. “All that desire and fear. We call it reality TV, now. We are used to seeing random strangers and putting them in crazy situations because we want them to argue and say stupid stuff. So we can laugh at them. We think: ‘Ha! I’m much smarter than that! Much saner than that. I’m on the right side of the wall.’ It is the same thing.”

At the Salpêtrière’s annual Mad Women’s Ball, the hospital’s “hysterical” inmates were given fancy-dress costumes to wear. They were dressed as mermaids, milk maids and flamenco dancers. Gleizes managed to escape from one ball while dressed as a man.

But Mas says, “It is important to say that the women seemed to suffer fewer problems in the weeks before the ball. They had a focus and something to look forward to. Just as the elite looked forward to their visit to the madhouse, so some of the patients – the poorest in society – were excited to mix with the elite. I took the liberty of describing both attitudes in my book.”

One of the most moving aspects of The Mad Women’s Ball is the sense of sisterhood between the women. The head nurse forms a deep bond with one of her patients. A middle-aged prostitute knits shawls for the younger women.

“Feminism has historically differed between French and anglophone cultures,” says Mas. “Yet it seems today that a common ground has been found. Feminist issues are now one global cause. But I wasn’t thinking about ideologies, about feminism, when I wrote this book. I wanted to include the nuance. Which is why there are characters like Eugenie’s brother, who thinks differently to other men and whose life is almost as restricted by the patriarchy as hers. It was really important to me to include the nuance. Charcot himself isn’t in the book very much. I didn’t want to depict him as a very cold doctor, even though he was a divisive figure… I think he genuinely wanted to help the women in his care, but… it is for the reader to decide.”

The novel has won a number of literary prizes in France, and Mas is delighted that it has been made into a film, which will be streamed on Amazon in the autumn. “With global hits like Call My Agent and Lupin, French culture is definitely having a moment. There is so much talent around.” But Mas didn’t get involved in the film? “No! I am excited to see what they have done with it, but if they asked me to remove a character or a story it would feel like chopping off a limb.”

For the quiet Mas, publishing a novel has been a huge statement. “I write, in the book, about how male anger turns outward and female anger too often inward,” she says. “But this novel… hmm… it has been my way of shouting. Shouting politely,” she grins, “and without having to make a sound.”

Prizewinning French bestseller ‘The Mad Women’s Ball’ by Victoria Mas is published by Penguin Books

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments