Tonke Dragt's The Letter for the King has finally been translated into English ... 50 years on

The coming-of-age tale about a boy and his mission to save a mythical kingdom was written in 1962 by an eccentric Dutchwoman and has sold a million copies. Will it, ponders Simon Usborne, herald a new publishing era?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A burglary confirmed Adam Freudenheim's suspicion that he was in possession of something valuable. The publisher and his wife, Victoria, had been asleep at a seaside cottage in Scotland when, at first light, an intruder crept unnoticed into their bedroom and removed a sheaf of paper from a drawer. It contained the last chapters of De brief voor de Koning ("The Letter for the King"), a coming-of-age adventure about a boy and his mission to save a mythical kingdom.

For months last year, Freudenheim had been receiving pages as quickly as his translator could produce them. The urgency was partly commercial. The book had already sold more than a million copies since it held rapt the first of generations of Dutch children in 1962. Yet, despite a pile of awards and fans in 15 languages, it had not yet been translated into English. Freudenheim hoped that the new edition would spearhead the children's list he had just launched at Pushkin Press.

But there were domestic pressures, too. "I was reading it to my kids and I'd get to the end and they'd say, 'We want more!'" he recalls. "I'd tell them, 'I'm sorry, I don't have any more,' and I would have to get back in touch with the translator."

Max and Susanna, then aged eight and nine, were captivated by the fate of Tiuri, a 16-year-old boy and son of a revered knight. Interrupted as he waits inside a chapel that he has been instructed not to leave under any circumstances before he is to be made a knight himself the next morning, Tiuri is compelled to break the rules by an urgent knock at the door. The future of the medieval realm depends on the safe delivery of the book's titular letter, he learns. But he must not read it. The mission serves as a moral test as Tiuri starts a perilous journey towards adulthood.

In Scotland, Freudenheim finally had the last of the book's 500 pages. He would only become aware of the theft and its perpetrator the next evening, when Max seemed to be impossibly familiar with the story's ending. Desperate for more, he had been unable to sleep and, sitting alone in his room soon after 4am, he wrestled with his own morals. As the sun came up, he decided to embark, on tiptoes, on a rule-breaking mission.

"As a father it doesn't get much better than that," a forgiving Freudenheim says. "And as a publisher it was wonderful. I knew I was on to something good."

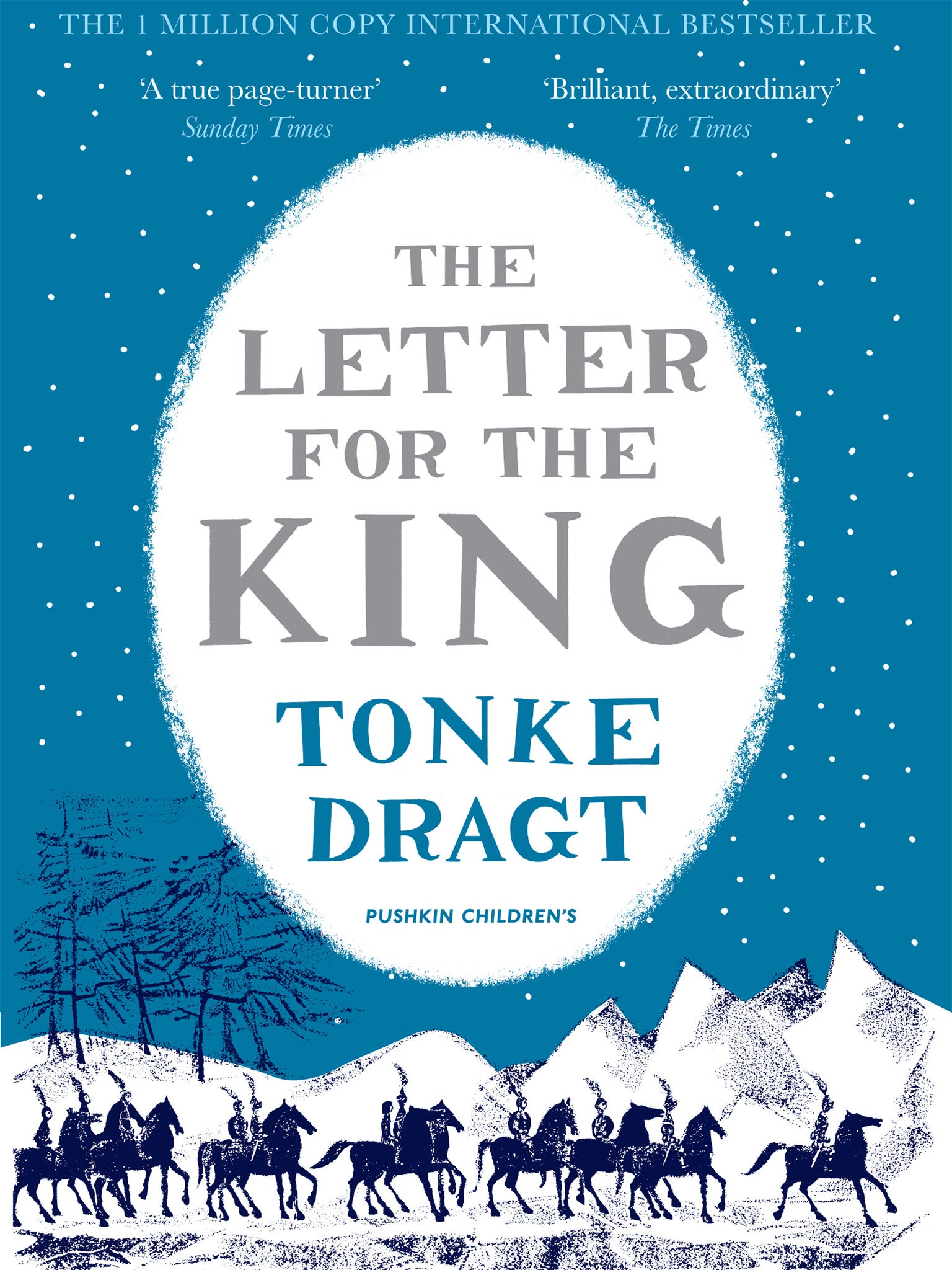

A year after its belated publication in English, The Letter for the King has hooked thousands more children and adults. Written more than 50 years ago by Tonke Dragt, an eccentric former prisoner of war, the book is next week being republished in a new, winter edition. Last week, it appeared on the shortlist for the Marsh Award for the best children's book in translation. Several critics named it among their books of 2013, comparing it to the works of Tolkien, Lewis and Rowling. There are now plans – secret for now – for a big-budget TV adaptation.

The book's own long journey from the once-imprisoned, yet rich, mind of Dragt, who still inhabits the mythical worlds she wrote and drew, reveals much about the author's enduring appeal, as well as our linguistic neglect of so much foreign fiction. Because in the Netherlands, where, in 2004, The Letter for the King won the "Griffel der Griffels" award for the best children's book of the previous 50 years, the story needs no introduction.

"Everyone I speak to who has grown up here says that it's their favourite book and can't believe it hadn't been translated," says Laura Watkinson, the translator who sent the story in chunks to an insatiable Freudenheim and his children, who are now 10 and nine. Watkinson had recommended the book in a meeting with Freudenheim after the publisher appealed for undiscovered children's fiction. "The name of the main character is not Dutch but there are now children here called Tiuri, it's huge," the translator adds from her home in Amsterdam.

Watkinson, who is now immersed in Dragt's 1965 sequel, Geheimen van het Wilde Woud ("Secrets of the Wild Woods"), had already produced a short excerpt in English and sent it to Freudenheim. "I was immediately captivated and knew right away we had to buy the rights to this book," he says.

Freudenheim, a Baltimore-born Londoner and former bigwig at Penguin Classics, bought Pushkin in 2012, and continues its mission to unearth books buried in their own languages. The children's list followed last year. "I think people still don't realise just how little there is that gets translated," he says. "There are obvious classics such as Asterix and Tintin but, once you get past picture books, and particularly in the aged six to 12 range, you just didn't find much at all."

There are clear reasons for the shortfall, not least the abundance of books in English, as well as the complacency that that can breed. "But there are so many more classics and fantasies that are timeless and have not been translated," says Watkinson, who also works in Italian and German. "I have a few more up my sleeve."

Publishers find hope in the adult fiction market that the gap might yet be filled. Next month, Penguin Classics will publish a book that has waited far longer to find an audience in English. Tales of the Marvellous and News of the Strange is a collection of Arabic short stories written at least 1,000 years ago, surviving today in a manuscript at a library in Istanbul. Their authors are unknown but now Malcolm C Lyons, a British expert in Arabic literature, has translated them into English.

The publication, late by a millennium, comes amid record demand for translations fuelled by blockbusters such as Stieg Larsson's Millennium series (75 million copies sold in 50 countries) and the works of Jo Nesbo (23 million copies). In December, Harvill Secker, another company specialising in translation (and Nesbo's publisher) will release Haruki Murakami's short work The Strange Library in time for Christmas, only weeks after fans of the Japanese author lined up to buy Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage.

According to the only research of its kind, by Literature Across Frontiers – a group based at Aberystwyth University – fiction, poetry and drama in translation in the UK grew by more than 40 per cent in the decade to 2010, to more than 800 works a year. Yet they still account for less than 5 per cent of new shelf space. Alexandra Büchler, the group's director, says that growing awareness, "nimble" publishers, and the grants that many countries offer English publishers all help. "But public support for translation is still very low, not to say negligible, compared with other major EU countries," she says. "We need to address this if we want to see it really thrive."

There are no clear statistics on children's books in translation but Freudenheim says he would be "surprised if it were 1 per cent" of the market. "To be fair, you can already get a rich variety of children's book written in English from Canada, Australia or India, for example," he says. "It's not that I'm saying that 50 per cent of children's books should be translated, but we are still at the other extreme, and most other countries translate far more."

Pushkin Press is careful not to market its works as translations but rather as great books. There is nothing on the front or back cover of the new edition of The Letter for the King to suggest its origins (you have to turn to the book's title page, after Dragt's map of her made-up realm, to find Watkinson's credit). "In a way, there is nothing Dutch about this book which is relevant to its international success," Freudenheim says. "It's not a Dutch medieval world, but an imaginary one. Most great books transcend their national setting and language and can speak to people anywhere."

Pushkin helped market The Letter for the King by leaving more than 100 copies on London Underground trains for people to discover. The books carried a letter for the reader, sealed with wax, with instructions to spread the word via mouth and social media. Tomorrow, First News, the weekly children's newspaper, is launching a Dragt-inspired letter-writing competition to encourage young readers to engage in an endangered art. The prize: the winner's height in books for his or her school's library.

Watkinson says it is those books that are more rooted in place and time which need to be translated as they are released, "so that there is still a freshness to them. Then they have the chance to become classics in English as well." Until that happens, she is looking for other pre-cooked classics. But her priority is Dragt's sequel, which, as with The Letter for the King, will take up to a year to translate (publication is expected next September). It gives a leading role to Lavinia, a girl who pops up in book one. "She's very adventurous and ahead of her time," Watkinson says.

Sometimes translators develop a relationship with the author but it wasn't possible for Watkinson; Dragt will be 84 next month and has struggled with illness in the care home where she now lives. Joukje Akveld, a Dutch journalist, was asked to write a biography of Dragt for children after a 2008 movie adaptation of The Letter for the King made it only more famous in the Netherlands. After several meetings with the writer, she published ABC Dragt last year.

"Tonke started as a school teacher and then got successful in writing quite soon, so she could live off her books," Akveld says. "But she really lives in those books as well. You can ask her about the characters and she really knows them like family. If you like stories as much as she does, you almost don't need the real world."

It would be easy to trace Dragt's imagination to her upbringing in Jakarta, the former capital of the Dutch East Indies. Born Antonia Johanna Dragt in 1930, she was the eldest child of a Dutch government employee who became a prisoner of war under Japanese occupation. In 1942, the whole family was interned and a teenage Tonke would beg for scraps of paper on which to imagine new worlds. Writing offered escape, "but Tonke thinks that's bullshit", Akveld says, adding: "She's not a lady who shows the backside of her tongue, as we say here. She told me, well, some things you just can't explain."

The family settled in the Netherlands after the war, but Dragt never married or had children. Most of Akveld's interviews took place in a café near the author's former home in The Hague, but occasionally she was invited inside. "Tonke is someone who can't throw anything away," she recalls. "Everywhere, there were books and drawings. There were also dolls' houses. When she started a new book, she built a new little house herself so she could really know the way the doors opened, for example."

The Letter for the King was only Dragt's second book, after she published her first in 1961. More than 15 books followed, all written and illustrated originally by hand until 2007, when age and arthritis got in the way. Dragt was unable to respond to questions for this article, but Freudenheim says that he has pinned by his desk a postcard from her, expressing her delight about the new translation. "It's such a pleasant surprise for her that the book is getting this new lease of life after more than 50 years," he says.

The new winter edition of 'The Letter for the King', by Tonke Dragt (Pushkin's Children's Books, £7.99), is available on 6 November

Swords drawn in castle mistrinaut (An extract)

Tiuri snapped into action. He stepped backwards, turned and ran, as quickly as he could in his long habit and the chainmail he was wearing beneath it. He ran across the courtyard, with the knights following him, their feet thudding on the wet ground. He did not intend to escape; he knew that was impossible. As he ran, he untied the rope around his waist and let his habit fall. Then he stopped, turned and drew his sword.

The Grey Knights were close behind him. Three of them also stopped, but the fourth came charging onwards at Tiuri, his weapon ready to strike. But when he struck, the blow was parried! Tiuri had taken him by surprise. He slashed at the knight so viciously that he made him stumble. The knight was soon back on his feet, but he staggered. Tiuri braced himself, sword in one hand, dagger in the other. He was no longer thinking about his fear and felt only a burning desire to fight.

The other knights stood there for a moment; they appeared to be hesitating. Then one came closer and attacked Tiuri. Their swords clashed fiercely. Tiuri fought like a man possessed. He was fighting for the letter – and for his life. He beat back his opponent, but he saw the next one waiting to take him on and he thought: They're going to keep on fighting until I'm defeated… dead!

But the knights seemed to be hesitating again. They were standing close together and looking at one another. Tiuri realised the drumming had stopped. And then, once again, he shouted, "What do you want from me? Speak! Challenge me if you must, but tell me why!"

For a few moments, it was so silent in the courtyard that he could hear the gentle sound of the rain falling. Then one of the knights whispered something to his fellows.

"Are you truly knights?" called Tiuri. "Or just cowards who conceal yourselves behind closed visors? Tell me who you are!"

One of the knights turned to Tiuri and said, "And who are you?" Tiuri recognised the voice of the knight with the silver horn. "Because one thing is certain: you are not Brother Tarmin of the Brown Monastery."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments