To split infinitives or not? The Independent's John Rentoul and The Times's Oliver Kamm talk superstition, convention and pedantry

When does grammar watchfulness become wordy nitpicking? Oliver Kamm, author of a new, convention-busting guide to English usage, challenges John Rentoul, collator of the ‘The Banned List’, to split an infinitive – and worse…

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.John Rentoul: Well, this is a bit awkward. Having read your book, I agree with much of it. A lot of grammar pedantry is mere fussiness and some of it is ignorant. I share your impatience with people such as Simon Heffer, the author of Strictly English: The Correct Way to Write… and Why it Matters. He is nostalgic for a past that never existed – and for someone who offers advice about style, is a poor stylist himself.

Still, I think there is a difference of emphasis between us. Indeed, I was embarrassed to feel that you were addressing me on page six, where you say: "It's irksome to be accused of arguing that 'anything goes' in language." I may have said something like that. But when you say that it is best to ignore what you call superstitions about, for example, split infinitives or "irregardless", I worry that some people might take you at your word. This would not be in their interest. As you accept on the previous page, it is "helpful to know the conventions of usage" so that you won't be "instantly dismissed for some perceived solecism". I agree with you that many of these conventions are mere superstitions, but any writer or speaker benefits greatly from knowing them and avoiding them, because by doing so their audience will think that they are cleverer than they are.

Oliver Kamm: Many thanks for the kind words. There is indeed a difference between us still. In my book, I distinguish between rules of grammar, conventions and superstitions. The rules are things like word order and inflection for number or tense. Native speakers (and the many non-native speakers whose command of English is indistinguishable from that of fluent native speakers) have already learnt these rules and faultlessly recall them.

Conventions are things like the case of conjoined pronouns. For example: contrary to the pedants' claims, it is not wrong to say "between you and I", but there is a convention in Standard English to say "between you and me".

And then there are things that are touted by pedants as rules, yet are not and never have been part of the grammar of Standard English. Prohibitions on split infinitives, stranded prepositions, dangling modifiers, fused participles and the whole dismal catechism of the sticklers have absolutely no effect on prose except to clog it up and make it stilted.

My advice to readers looking for guidance on usage is that when they follow conventions, they are expressing a stylistic preference – comparable to the stipulations of the style guides that your newspaper and mine issue to journalists. That's all. Their merit is consistency not correctness.

And when readers encounter a superstition (otherwise known as a shibboleth or a fetish) they should go right ahead and break it. Their prose will be better for it.

It is that last point on which we differ.

JR: I completely agree with you about conventions and superstitions. I very much enjoyed your examples of Jane Austen using "they" as a singular generic pronoun. And the several instances where the sticklers insist that some new meaning of a word is wrong, where you show that its earliest uses were in precisely that sense. Particularly enjoyable was your citation of the earliest recorded use of "supersede" in 1491, spelt "supercede". Yet, as you say, there is a difference between us. You say that, when someone encounters a superstition, "they should go right ahead and break it". That is fine for you to say: you are a confident and experienced writer. Your writing has a reputation for clarity and precision. When you end a sentence with a preposition, your readers know you mean it.

But for less experienced writers, I fear your advice is unhelpful. They don't need to know that a rule, such as that against split infinitives, was invented by 19th-century self-appointed grammarians. They need to know that a lot of people – like your former boss at the Bank of England – still think it is a rule and will judge you for it.

You say that if someone breaks a rule that you regard as a shibboleth or a fetish, "their prose will be better for it". But that is just your opinion. I might even agree with it. But, as you say to those you call sticklers, it is just a stylistic preference. What is important to a writer seeking to gain a hearing is that there are a lot of sticklers out there, and one of the people who reads their article might be the person who gives them a break. You make this point yourself in the book. I hesitate to accuse you of inconsistency, but I think you need to sort this out.

OK: I don't claim to be consistent: I claim to be right. Even so, I cordially suggest that the problem of inconsistency is one that applies to your side of this debate rather than mine.

My argument is not against rules of grammar and conventions of usage. It's rather that what are generally touted as rules of grammar are no such thing. They're bogus, pointless, fabricated superstitions that were invented by autodidacts in the late 18th century or later, and that are contradicted by the evidence of usage.

As I understand it, you agree with my argument yet advise young writers to behave as if it's never been made. You maintain that whereas we're sophisticated enough to know that the sticklers are wrong, there's pragmatic value for others in nonetheless pretending that they're right. That's poor advice.

First, though I won't criticise anyone for following sticklers' stipulations if they really want to, doing so damages fluency. Here, almost at random, is a statement by the Tory MP Francis Maude, made on the day I write this: "There will never be a time when you don't have constantly to make sure the party is in tune with Britain as it is."

What an extraordinary place to put that modifier ("constantly"). An articulate native speaker wouldn't write something as stilted as that unless under the impression that there was a grammatical rule requiring it.

Second, it's impossible to consistently follow all the sticklers' edicts, because they are incompatible and wild. NM Gwynne, for example, denounces as "illiterate" the use of "per capita", and advises instead using "per caput". Anyone who wants to be laughed at is welcome to adopt such a fanatical indifference to English usage.

Third, the sticklers' edicts are not some benign if eccentric stylistic preference. They are a means of keeping social divisions sharp, and always have been; of denoting the "in crowd" as against the populace. Let's be done with them, and call them for what they are.

JR: You may be right that some supposed rules of grammar are bogus, or that some supposedly new usages have an ancient precedent, but I thought your argument was that there is no right or wrong in English usage, merely convention and stylistic preference.

If so, I would agree with you. But I would not advise young writers to behave as if your argument had never been made – on the contrary, I want them to know about it and to use it to help them to avoid putting off readers needlessly. They need to know that there are lots of people among their potential readers who care about split infinitives. (Incidentally, I think your Francis Maude example is a poor one: it's not the unsplit infinitive that makes it hard to read but the double negative and the oddness of "Britain as it is".)

I don't think we should – and as you point out, we couldn't – follow all the sticklers' edicts. I merely say we should know about them. It is worth avoiding usages that most readers or listeners believe to be errors. It is even, to come to your last point, worth avoiding them if a significant minority of readers or listeners believe them to be the mark of someone less well educated than them.

I am only trying to help.

OK: Sure, there are right and wrong ways of saying things. My difference with the sticklers is this: to determine what's right or wrong in English usage, it's essential to look at the evidence of usage. You and I, and our respective newspapers, may make errors of grammar and orthography, but it's not possible for everyone – or even for many users of the language – to be wrong on the same linguistic question at the same time. In the apt phrase of Steven Pinker, whose most recent book is The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person's Guide to Writing in the 21st Century, the lunatics are in charge of the asylum.

Determining the rules of English grammar is a matter for investigation rather than edict; the magnificent Cambridge Grammar of the English Language takes 2,000 pages to discuss them. Moreover, the range of legitimate variants even in the grammar of Standard English, let alone of other dialects, is far wider than the sticklers imagine.

I quite agree that it's worth knowing the sticklers' purported rules. They're of historical importance, and scholarly linguists (for example, Anne Curzan in her recent book Fixing English: Prescriptivism and Language History) have looked closely at their role in the development of English. But that's much like saying it's important to know about Christian doctrine because it's played a central role in British history: it doesn't make it true.

My objection to the sticklers is comparable to the problem Christopher Hitchens had with religious believers. It's not enough for them to have faith that they belong to the elect: they have to harangue the rest of us about it. Well, I've had enough. The historical and literary evidence doesn't support them, and it's time to fight back.

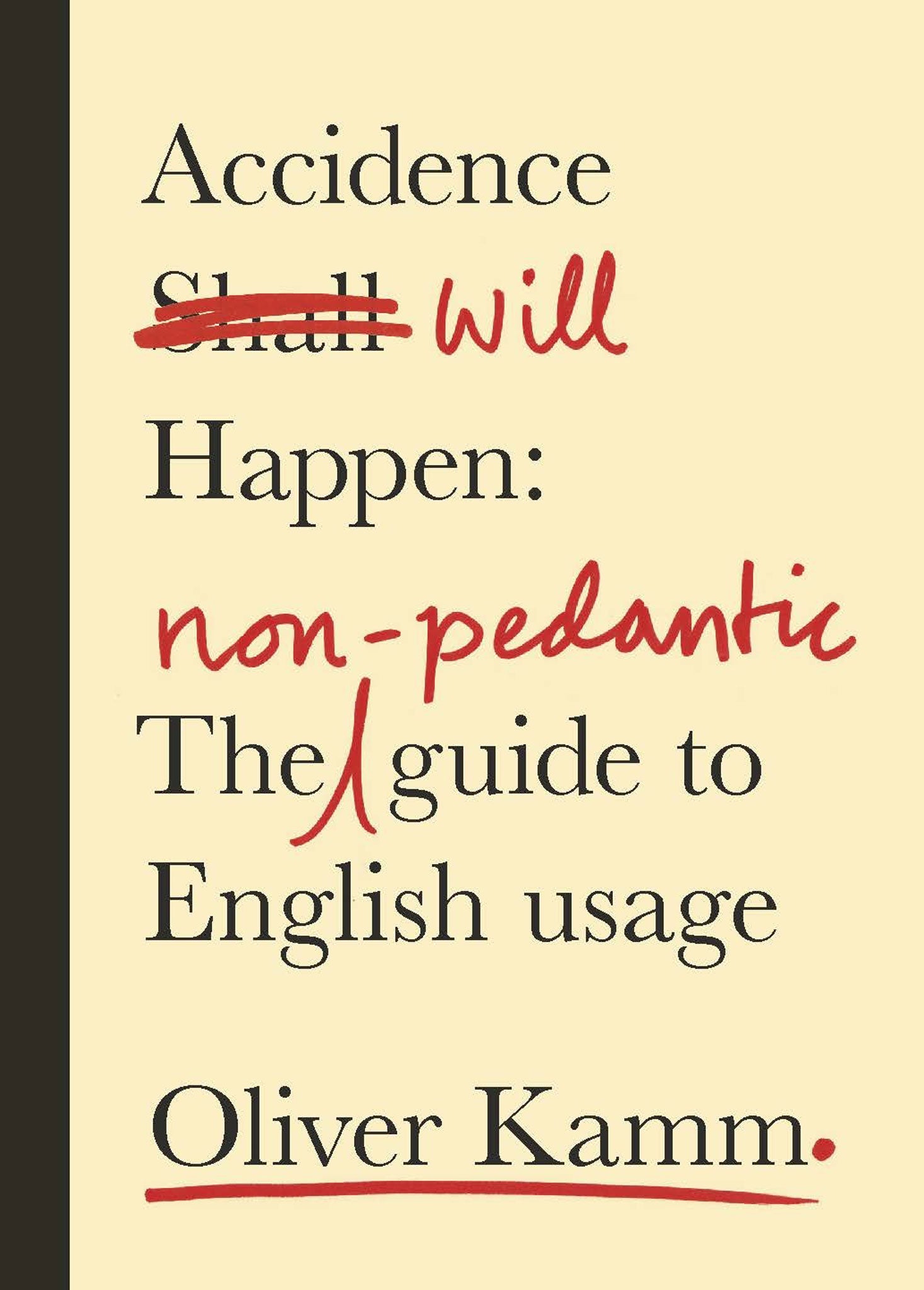

'Accidence Will Happen: The Non-Pedantic Guide to English Usage', by Oliver Kamm (£12.99, Weidenfeld & Nicolson), is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments