The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

What happens when books inspire real-life violence?

Some elements of the storming of the US Capitol on 6 January echo the violent novel 'The Turner Diaries'. Clémence Michallon investigates the complicated history of books which intersect with brutal events

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When a crowd of violent insurrectionists stormed the US Capitol on 6 January 2021, two emotions dominated the public discourse: bewilderment, and a sense that this was the culmination of a four-year build-up. The insurrection was shocking and deadly. One after the other, images trickled down: there were broken windows, face-offs with police. A man gleefully posed for a photo after picking up the lectern of Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi. Another sat in her office chair, one foot resting on top of her desk.

But as the crowd ransacked the seat of the legislative branch of the US government, it was hard to shake the feeling that this was the culmination of four years of brazenly divisive rhetoric by the White House – and decades of white supremacist sentiment.

To Talia Lavin, a writer, researcher, and the author of Culture Warlords: My Journey Into the Dark Web of White Supremacy, some of the images coming from the Capitol felt eerily familiar. Part of her research has focused on The Turner Diaries, a novel published in 1978 by white supremacist and neo-Nazi William Luther Pierce III.

Described by the Anti-Defamation League as “lurid, violent, apocalyptic, misogynistic, racist and anti-Semitic”, The Turner Diaries depicts a violent overthrowing of the US government. Since its publication, it has become a staple of white supremacist circles, inspiring what Lavin describes in her book as “an extraordinary amount of violence”. Most infamously, excerpts from The Turner Diaries were found in the getaway vehicle of Timothy McVeigh, one of the domestic terrorists behind the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing that left 168 dead.

The Turner Diaries received renewed attention after the insurrection. To Lavin, there isn’t necessarily a “one to one correspondence” between the book’s plot and the events of that day, but some elements of the storming of the Capitol clearly echo the novel. “For example, ‘Murder the media’ was scrawled on a door at the Capitol,” Lavin says. “Killing journalists is a huge fantasy point in The Turner Diaries.” The same goes, she adds, for the idea of “mass hangings”, a “pretty crucial part of the narrative of The Turner Diaries” that came to mind when a noose was erected outside the Capitol.

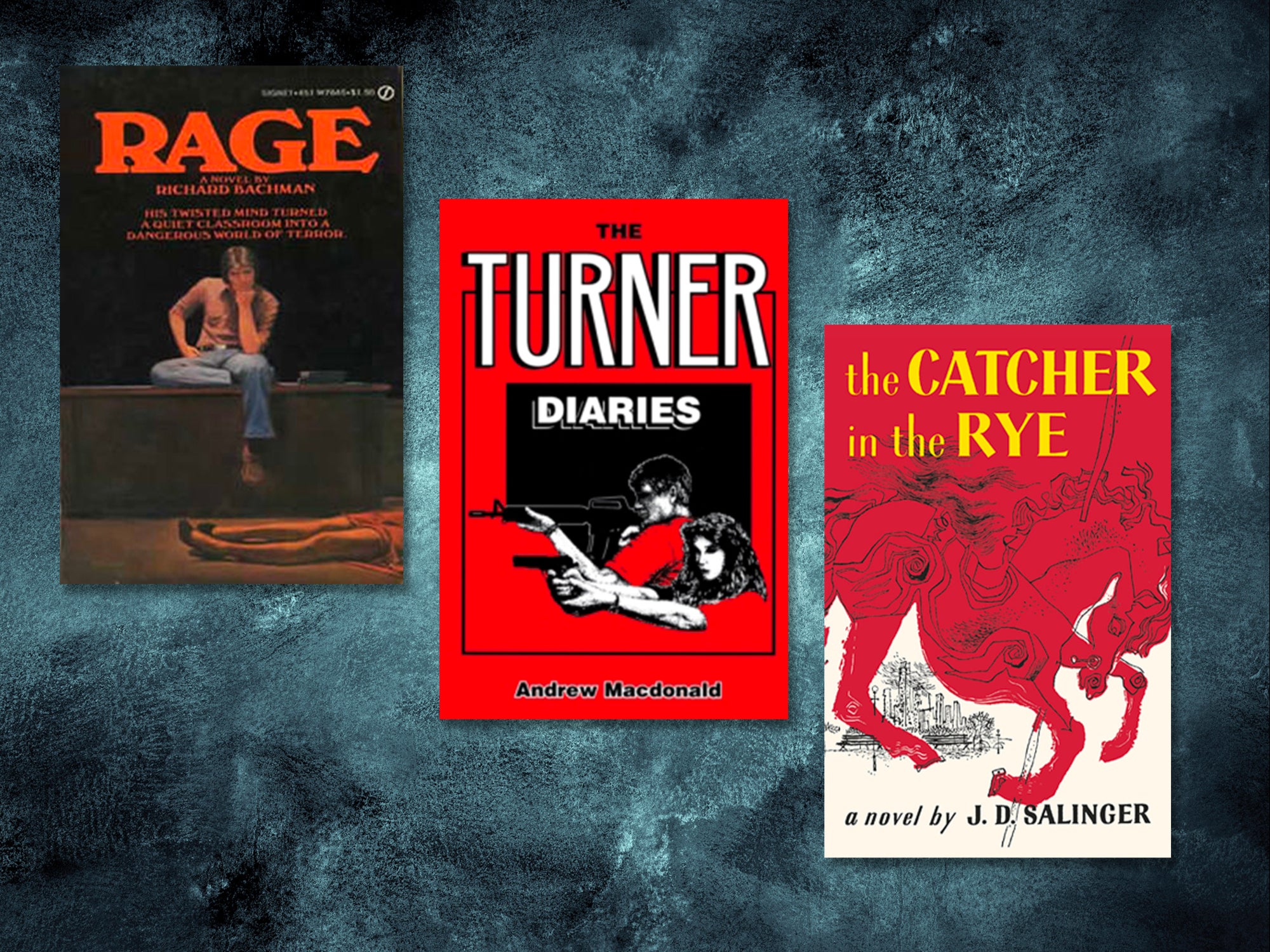

The Turner Diaries is far from the only book tied to real-life violence: Stephen King’s Rage and JD Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye are just a few titles. But the line between the events depicted in Pierce’s novel and the acts it seems to inspire is strikingly direct. At its core, The Turner Diaries isn’t art; it’s a manifesto disguised as a thriller-style novel – “the far-right version of a Marvel movie”, as Lavin puts it.

Despite that, The Turner Diaries was available for purchase on Amazon until recently. The website pulled it from its digital shelves following the Capitol insurrection, as reported in January by The Verge. Prior to that, in 1996, author and publisher Lyle Stuart decided that his company, Barricade Books, would publish and distribute the novel, a move he justified to The Washington Post by stating: “I'm a nut, on just a few things in life. ...I'm a great believer in letting anybody publish the most outrageous, unpopular things there are."

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, half a million copies of the book had been sold by 2000. And based on Lavin’s research, a PDF copy of The Turner Diaries remains a “totemic” possession in white supremacist circles, akin to a status symbol. “Nut” or not, it begs the question: wouldn’t we be better off without The Turner Diaries?

For Lavin, there is value in making the book harder to access commercially. “Any time you take an action to make an extremist task or group or speaker a little harder to find, you will deter [people],” she says. “Even one person deterred has value.” When I bring up the idea of a government-enforced ban, though, Lavin – “not a free speech absolutist” by any means – worries about the consequences: “I think we do ourselves a disservice by pretending that the law enforcement apparatus in the US is politically neutral. Any law that came down to ban extremist material might end up disproportionately affecting the left.” Rather than legislation, Lavin is in favour of “a collective social response” to “make it unprofitable to sell hate”.

Books impact real life, but real life impacts books, too. Two decades before Amazon stopped selling The Turner Diaries, a different novel disappeared from view almost completely – this time by its author’s own volition.

In 1977, King published the novel Rage, about a “troubled boy” who “takes a gun to school, kills his algebra teacher, and holds his class hostage”. In the 1990s, King became aware of two high school shootings in which perpetrators either referenced Rage or were found to own a copy of it.

“That was enough for me,” King wrote. “...I asked my publishers to pull the novel from publication, which they did, although it wasn’t easy.”

In Guns, a thoughtful nonfiction essay published by King in 2013 on the issue of gun violence in America, the author states that “it took more than one slim novel” for the perpetrators to carry out the shootings, and explores other factors such as access to guns. “They found something in my book that spoke to them because they were already broken,” King writes of the shooters. “Yet I did see Rage as a possible accelerant, which is why I pulled it from sale.”

King isn’t the only author who’s had to preoccupy himself with the potential for school violence. When Lionel Shriver sent the manuscript for what later became her bestselling success We Need To Talk About Kevin, about a fictional school massacre, her “usually responsive agent went silent for weeks”. “My timing was mythically crap,” Shriver later recounted in an essay for The Guardian. “I submitted the final draft to my New York literary agent right after 9/11, in that hilarious little window when everyone thought Americans would never read or watch anything violent again.”

When Shriver’s agent finally got back to her, according to Shriver, the agent struggled to see where the book would fit in the market, and “worried the plot might invite copycat killings”. To this day, that fear appears to have been unfounded: the book, as well as its film adaptation, have not been directly tied to any specific acts of violence. (Shriver eventually sent the manuscript directly to a small publishing house, which took it on.)

Look up “books that inspired crimes”, and – along with Rage and The Turner Diaries – a familiar title will crop up. The Catcher in the Rye, Salinger’s 1951 coming-of-age classic, is indelibly tied to the 1980 murder of John Lennon. The musician’s killer, Mark Chapman, had a copy of the novel with him during his arrest; as reflected in a New York Times article published ahead of his trial, Chapman himself sought to emphasise the impact of the novel on his psyche, claiming that reading it would “help many to understand what has happened”.

The stigma, according to Salinger biographer Kenneth Slawenski, was such that after the shooting, “the ongoing joke – and it was only half of a joke – was that if you went on the Subway, you should carry a copy of The Catcher in the Rye and put it on your lap, and nobody would mess with you.” Notably, according to the Carnegie Mellon University’s Banned Book Projects, at least nine attempts to ban the book from various US schools between 1986 and 2000 were based more on the novel’s “use of profanity and sexual references” than on preoccupations with real-life violence.

Of course, Catcher didn’t kill Lennon any more than King’s Rage caused school shootings. To make that argument would be like blaming video games, films, or rock music for various acts of violence: inaccurate and shockingly reductive. Examining books whose histories have intersected with violence is interesting, in most cases, if we allow these books, and our relationships to them, to teach us something about ourselves.

Sometimes, the lesson is straightforward. Take The Turner Diaries: it’s not hard to imagine why white supremacists would take to it. With Catcher, things are murkier: the tale of Holden Caulfield, a 16-year-old boy wandering New York City after being expelled from his prep school is not, on the surface, the type of narrative that would inspire the deadly shooting of one of the world’s foremost celebrities.

Yet, the novel has been tied to at least two more instances of violence: John Hinckley Jr’s 1981 attempt to assassinate President Ronald Reagan (a copy of Catcher was found in Hinckley’s hotel room), and the 1989 murder of actor Rebecca Schaeffer by Robert John Bardo (who told police he tossed a copy of the book while fleeing the scene).

I read The Catcher in the Rye aged 15, the best possible age. Like so many other teens, I saw myself in Holden. His sense of alienation, his lonely search for authenticity, resonated with me. But the novel never stirred any feelings of violence in me. It wasn’t until years later that I found out about Chapman, Hinckley, and Bardo. What was it, then? What did these men see in Holden’s story that I missed?

Jess McHugh, the author of the upcoming book Americanon, a history of the US through 13 bestselling books, has spent time researching how books shape our world and identities. The books she examines in Americanon differ in tone and style from The Turner Diaries and even Catcher; she focuses on seemingly innocuous volumes such as Webster's Dictionary and Betty Crocker's Picture Cook Book. Bestsellers, she says, serve as a “litmus test”, a mirror of society that can reveal “some sort of hidden anxiety, fear, prejudice” at play at the time of their successes.

“A book is like a living thing, almost like a child is to a parent,” she says. “The book goes on and lives its own life. Sometimes, the readers influence the life of a book even more than the author.”

That is the case, she adds, for Catcher: “It has this really wild metamorphosis where it goes from being this book written by this 30-something-year-old, kind of strange man, to a manual for discontents. And now, it becomes something else entirely. It’s a national punchline. It’s the shorthand for prep school boys with terminal uniqueness syndrome. ...It really has led its own life, so separate from the page and from Salinger himself.”