The story of William McGonagall, the worst poet in the history of the English language

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 1877, 40 years into the reign of Queen Victoria, an anonymous letter arrived at the offices of the Dundee Weekly News. It was a message in doggerel rhyme, a tribute to a local vicar who "has written the life of Sir Walter Scott/ and while he lives he will never be forgot/ nor when he is dead/ because by his admirers it will be often read."

The editor thought it jolly enough, and published it in the section for readers' correspondence, with a jokey little note that its writer "modestly seeks to hide his light under a bushel".

Oh dear. There is a saying among journalists that "there is no such type font as Times ironic" – a warning that if you use irony in print, you run the risk that a reader with a sense of humour deficiency will take you literally.

The anonymous author of the solemn "Address to Rev George Gilfillan" was indeed short on humour, and on self-awareness. Modest was not an adjective that suited him either. He was a serious, devout, teetotal family man, with six children, aged either 47 or 52 (he was never clear about his own date of birth) who believed that God had recently spoken to him with a voice that said: "Write! Write!"

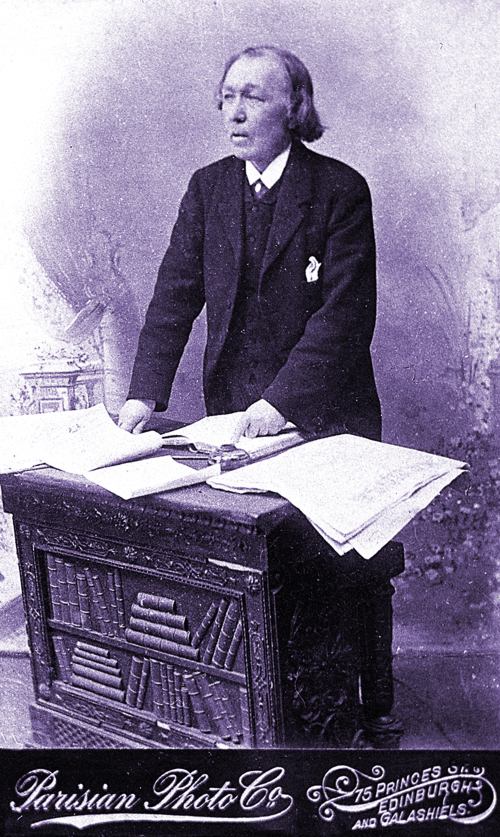

The note by the Weekly News editor only helped to solidify the conviction already forming in the mind of William Topaz McGonagall that his vocation was poetry. He followed it with heroic dedication for the remaining 25 years of his life, leaving behind a vast quantity of work, and a reputation that endures more than a century after his death.

Yesterday, a folio of 35 McGonagall poems, signed by the author, fetched £6,600 in the Lyon and Turnbull auction house, Edinburgh – the sort of money you would expect to pay for a first edition Harry Potter signed by J K Rowling.

Dundee, where the poet's career began, has a thriving McGonagall Appreciation Society. Dundee Central Library holds a William McGonagall collection in its local history section. An exhibition of art works based on McGonagall's poetry, by Edinburgh art teacher Charles Nasmyth, was published as a book last year.

Yesterday, the writer and comedian Barry Cryer went on the Today programme to pay tribute to the Dundee bard, and recite the only poem McGonagall was ever paid to write, which was an advertisement for Sunlight soap – "You can use it with great pleasure and ease/ without wasting any elbow grease."

As the excerpt demonstrates, it is not the quality of his poetry that has immortalised McGonagall, but rather the British love of heroic failures. We adore the little fellow with oversize ambition who won't give up even when it is blindingly obvious to everyone around him that he is bound to fail.

In his lifetime, he was a music hall joke – the Mr Bean of the Scottish cultural scene. He was paid five shillings for a public recital so that his mostly working-class audiences could jeer at his bad poetry or pelt him with rotten vegetables.

Unable to sell published poetry, he lived partly off the generosity of benefactors, who may have shared his almost insane belief in his talent, or may simply have enjoyed the joke. Though he had grown up in poverty, his verses are full of respect for his social betters, and for the Victorian mission to civilise the poor. He apparently thought that alcohol was to blame for his audiences' failure to appreciate his work.

When Dundee refused to recognise him for the poet he thought he was, McGonagall tried Perth, then Edinburgh, where he died in poverty in 1902. And yet, according to his illustrator Charles Nasmyth, the clumsiness of his verse can stimulate the imagination. "The lines of some of his poems are quite picturesque. They may not be good poetry but they create images in the mind," he said.

"When I read those lines from 'The Tay Bridge Disaster' which went 'When the train left Edinburgh/ the passengers' hearts were light and felt no sorrow/ but Boreas blew a terrific gale/ which made their hearts for to quail...', I had a vision of Victorian ladies and gentlemen sitting in a train, their chests bursting open and their hearts turning into quails and flying off.

"I think he was a man before his time. He was a 19th-century wannabe. I'm not one of those who think he was a great poet, but he actually lived out the part. He suffered for his art."

To be properly appreciated, McGonagall's poetry should be read aloud in a working-class Scottish accent, so that Edinburgh rhymes with sorrow – which is all that his efforts seem to have brought him.

He managed to travel, taking a boat trip to New York, subsidised by a wealthy benefactor. When he travelled, he reacted to what he saw in the manner of a poet, and recorded his thoughts in verse.

Mr Nasmyth, for instance, sees a parallel with Book VII of The Prelude by William Wordsworth, describing the sense of wonder and isolation he experienced after moving to London, where "The face of everyone that passes by me is a mystery."

McGonagall's visit to London was reputedly the outcome of one of many cruel hoaxes played on him. He was sent a fake invitation to meet the actor Sir Henry Irvine, but having made the 480- mile journey, he was turned away at the stage door. The experience gave rise to his "Descriptive Jottings of London", with its immortal opening verse:

As I stood upon London Bridge and viewed the mighty throng

Of thousands of people in cabs and busses rapidly whirling along,

All furiously driving to and fro,

Up one street and down another as quick as they could go...

"Here, you see, he has the same thoughts as Wordsworth," said Mr Nasmyth. "He just doesn't know how to express them well."

Verses such as these have given McGonagall the reputation as "the world's worst poet". But there is another way of looking at his life. Being a handloom weaver in Dundee must have been dull work, with no great financial security. The last 25 years of McGonagall's life must have been more interesting than the first 50, for all the hardship and ridicule.

"He is very much a heroic failure," said Mr Nasmyth. "And ultimately, to some extent, he has overcome failure... and achieved a sort of posthumous success."

The Tay Bridge Disaster

Beautiful Railway Bridge of the Silv'ry Tay!

Alas! I am very sorry to say

That ninety lives have been taken away

On the last Sabbath day of 1879,

Which will be remember'd for a very long time.

To The Rev George Gilfillan

He is a liberal gentleman

To the poor while in distress,

And for his kindness unto them

The Lord will surely bless.

Robert Burns

Immortal Robert Burns of Ayr,

There's but few poets can with you compare;

Some of your poems and songs are very fine:

To "Mary in Heaven" is most sublime;

And then again in your "Cottar's Saturday Night",

Your genius there does shine most bright,

As pure as the dewdrops of the night.

Jottings of New York

Oh mighty City of New York! you are wonderful to behold,

Your buildings are magnificent, the truth be it told,

They were the only things that seemed to arrest my eye,

Because many of them are thirteen storeys high.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments