The real 'Kes': The Barry Hines story was based on his little brother's experiences

The film 'Kes' and the novel on which it was based are acclaimed as cultural landmarks. But while Kes was my kestrel, says Richard Hines, I was no knave

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This article was originally published on 29 February

A few weeks after my 20th birthday, in 1965, on a warm June evening I set off on a walk to Tankersley Old Hall. When I reached the crossroads at the centre of the village, instead of going straight ahead up Tankersley Lane I turned left and walked down the turnpike. It was up this hill that, in 1843, the last horse-drawn stagecoach had travelled through Hoyland Common.

I knew this piece of Yorkshire history from talking to Arthur Clayton, a miner at Rockingham Colliery, who later became a published local historian. Arthur had discovered a newspaper advertisement from 1843, offering for sale the four horses that had pulled the mail coaches along this stage of the turnpike. Often Arthur was so fired up by his subject, oblivious to the cold, biting wind, or the crack of thunder, that he would keep me talking when I was impatient to be off. Yet when the weather was fine I loved to listen to him, and the local history he taught me added interest to my walks. For example, as I went down this section of the turnpike called Parkside, which still had an 18th-century milestone, I knew I was walking along the boundary of the medieval deer park which had once surrounded Tankersley Old Hall. That June evening as I climbed over a stile and into the parish of Tankersley and the fields which had once been the deer park, it fascinated me to think that in 1727, on his tour of Britain, Daniel Defoe had visited here and written that he believed the red deer in Tankersley Park were the largest in this part of Europe – before going on to make the exaggerated claim that one of them had been even bigger than his horse.

The land here had been divided by a stone wall into two fields. Early in spring, in the field to my left, lapwings had nested in scrapes of earth between green wheat shoots, and had risen and tumbled in the sky above my head, calling “peewit...peewit...”.

Now, in June, the corn was knee-high and had already begun to turn golden, and tall flowers – pinkish-purple foxgloves, white ox-eye daisies, red poppies – grew beside the stone wall. In the field over the wall to my right, black and white cows grazed and swallows flew low over the grass, catching insects.

Back on the path, I continued walking through the wood; and as I came out on to a cart track opposite Tankersley Old Hall I saw John, the lad who'd brought me the young kestrel that had died. He had an air rifle under his arm and was gazing across a field of buttercups at the ruins of the hall. As I approached him he smiled, but his eyes didn't look pleased to see me.

“Getting a kestrel this year?” I asked.

“Don't know,” he said.

“Does tha know a nest? I want to get one.”

“Wait here.”

Curious, I watched John walk down the track. After 50 yards or so he stopped, aimed his air rifle and fired at the ruined Old Hall. Moments later a kestrel flew out and disappeared over Bell Ground Wood.

A few nights later, around 11.30pm, John called at our house and I went out into the June night to join him. New council houses were being built on allotments at the edge of the village. Stepping over a pile of canes left from the previous year, the dead runner beans still attached to them, we spotted a ladder leaning against the scaffolding of a half-built house. Lowering the ladder to the ground, we carried it out of the building site. The moon was large and bright and the occasional trail of white cloud was visible against a dark blue sky. Cows watched us as we walked through the fields carrying the borrowed ladder between us. When we entered Bell Ground Wood, John let go of the ladder, cupped a hand around his mouth and struck up a conversation with a tawny owl. His every “Whoo-ooo” returned from within the dark wood like a ghostly echo. To our relief the lights were out in the farmhouse next to the Hall; the farmer's dogs were silent. We clambered over the wall and headed across the field towards the looming ruins.

The last tenant to live in Tankersley Old Hall in 1654 was Sir Richard Fanshawe, a Royalist in the English Civil War. In her memoirs his wife, Lady Anne Fanshawe, writes: “The house of Tankersley and Park are both very pleasant and good”, and while there, she and Sir Richard “lived a harmless country life, minding only country sports”.

Falconry was the rage back then. I'd read a vivid description of how to hood a hawk that had been taken from Edmund Bert's 1619 book An Approved Treatise of Hawkes and Hawking, and I was fascinated by the thought that, more than 300 years ago, Sir Richard would have probably read those same words.

As John and I placed the ladder against the wall, extending it so as to reach the kestrels' nest, I sensed a connection with Sir Richard across the centuries. He'd have known that hawks' nests were “eyries”, young hawks “eyases”, and that the correct term for fully grown feathers was “hard penned”.

I heard the “kikiki...kikiki” of the young kestrels as John examined them at the top of the ladder in the moonlight. In a loud whisper he told me the kestrels were still covered in down, too young to take. So we made a plan to come back in a week or so. The delay in getting my kestrel worked out well. I'd got a cardboard box ready to keep the young hawk in for the first night, but I hadn't had time to prepare the “mews”. We weren't taught French at secondary modern school but from my reading I'd discovered mew means “to moult”, which, although I couldn't pronounce it, originates from the French muer – to change the feathers. In the past the mews was where you put your hawk to moult – there used to be a royal mews at Charing Cross, until 1534 when the mews were converted into stables.

Standing in the doorway of our shed I gazed around in dismay at the chests of drawers, bikes and tools, wondering how I could turn the shed into a mews. I was considering moving all the clutter to one end and then partitioning off the remaining space, when I had an idea. I could ask my brother Barry if I could use the Second World War air raid shelter at the bottom of his garden. Barry agreed and cleared out the shelter. I sawed a window into the door, over which I fixed vertical wooden slats. In the wild, falcons stand on flat rock ledges – so on the inside of the door, just below the slatted window, I fixed a shelf perch where the young hawk could enjoy the morning sun.

That evening I sat at the kitchen table with my mother's sewing kit. I'd already made the hawk's jesses; my mother didn't want to part with her best leather gloves, but she'd searched out an old pair for me to cut up. I was now making the lure, in the form of a small leather pad. I wasn't very handy with a needle but I'd managed to sew up three sides of the lure, and was pouring in sand to give it weight, when someone knocked on the door. When I opened it I was surprised to find John standing on the doorstep, days before he was expected.

“Are we going tonight?” I asked. “I went last night,” he replied.

“Why didn't tha call round for me?”

“I did – there was nobody in,” said John, reaching inside his jacket and handing me a young kestrel.

My heart racing with excitement, I thanked John; then, with my thumbs across her back and my fingers gently pinning her wings by her side, I carried the young kestrel into the house.

Her head and back were reddish-brown with dashes of black. Wanting to get a better look, I tilted her slightly and saw her large brown eyes. What struck me most was the colour of her “cere” – the bare patch at the top of her curved beak – and the colour of her legs and toes. They were as yellow as buttercups. “It's not unlike a throstle,” my mother said, her eyes taking in the kestrel's speckled buff and black breast feathers.

A few weeks ago in early June, the hay meadow had been a pinkish haze of long grasses among which wildflowers bloomed: purple vetch, pink clover, buttercups. This evening swallows flew low, hunting insects over the freshly cut hay which had been raked into piles to dry. John's unexpected delivery of the hawk meant that I hadn't any food ready for her. It was legal to shoot sparrows in the 1960s and so, carrying my air rifle, I stalked the hedgerows. I wanted to give my kestrel the type of natural food she'd have been fed by her parents.

The dead body of the sparrow I'd shot was still warm, and its head lolled around when I knelt on the lawn outside the mews in Barry's garden, and placed it on an old bread board. To lessen the chances of anything sharp puncturing my young hawk's crop, I cut off the sparrow's sharp beak, then its lower legs, so she wouldn't swallow its claws. With a hammer I then smashed the bird's thigh bones. Picking up my knife again, I spread out its wings on the bread board, pressed the knife blade down hard and severed each one from the shoulder joint. I didn't want my bird swallowing any large wing feathers. Plucking the sparrow carefully, I left some soft feathers attached to its breast so the young kestrel could regurgitate a pellet of them, along with any small bones that she did swallow. Finally, I cut open the sparrow's breast and stomach to encourage my young hawk to eat the innards.

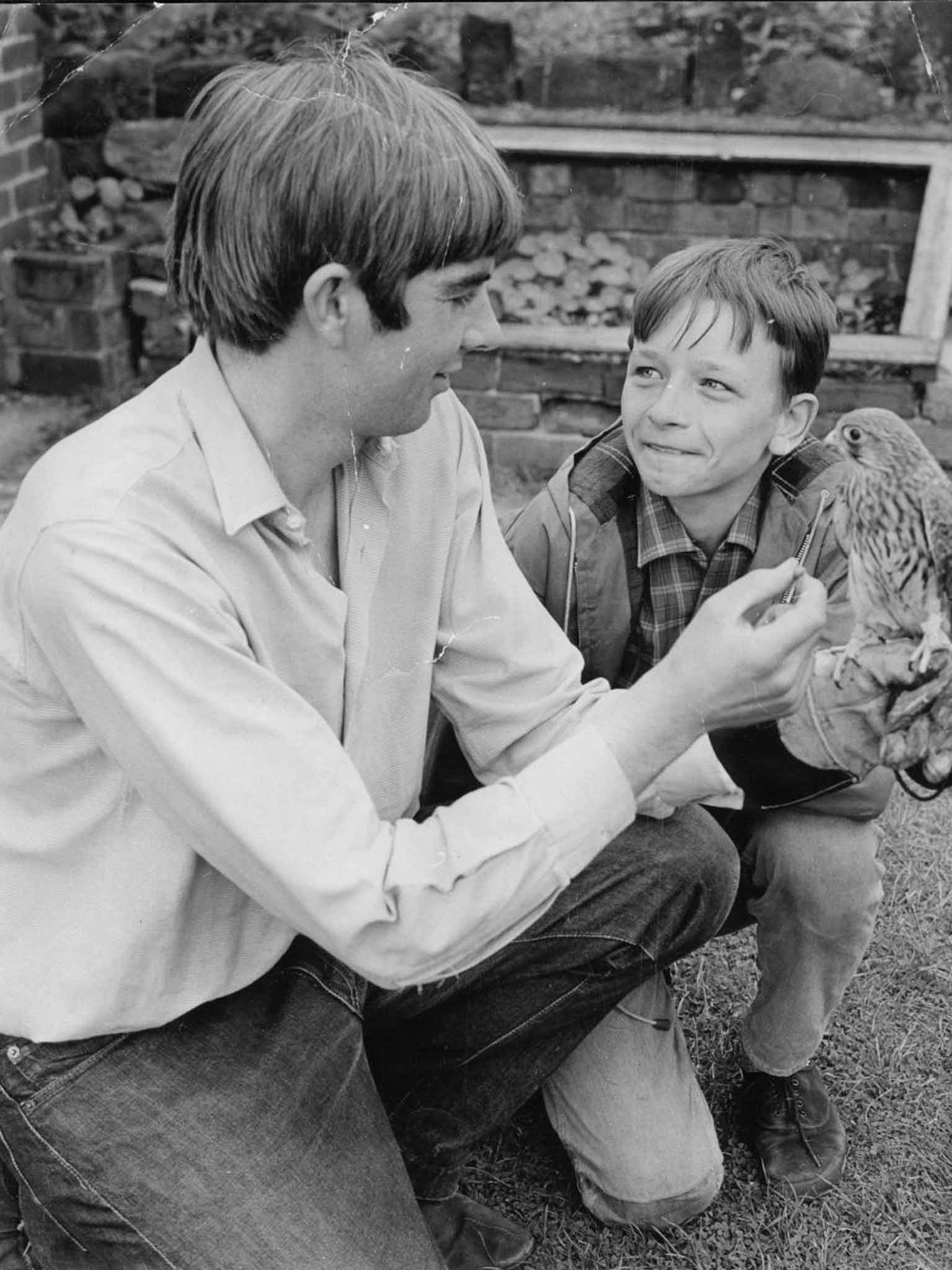

I now needed help, so I fetched Barry from the house and we entered the mews. The young kestrel gasped and struck out at my hands as I reached into the cardboard box. Covering her back with a large white handkerchief to prevent damage to her feathers, I pinned her wings by her sides and passed her to Barry to hold.

Reaching into my pocket I took out the pair of jesses which I'd cut out from my mother's gloves. I'd practised fitting the jesses around a pencil, and although the young hawk tried to grab me with her talons, fitting the first jess and tightening the loop of soft leather snugly around her leg was easy. As I fitted the second jess around the other leg I told Barry I was going to call my kestrel Kessy. Holding her in front of his chest as I gently tightened the jess, Barry suggested I shorten the name to Kes.

Sleek, her feathers held flat to her body in fear, Kes watched my hand move slowly towards her and place the opened-up sparrow on the perch. Nervously looking at me she showed no interest in it – so, reaching out slowly, I picked up the sparrow entrails upwards and held it in front of her feet. Shooting out a foot she grabbed it, then watched me back away before she began to tear at the deep red meat with her curved beak, gulping down the sparrow's heart, and swallowing its gullet as if it was a string of spaghetti. The stomach was still attached and swung like a pendulum before disappearing down her throat. Today I can order frozen hawk food on the internet and have it delivered to my door next day.

As the days went by, when the birds saw me wandering the hedgerows of the meadows and crop fields with my air rifle, they cottoned on to what I was up to, and often flew away before I could get close enough to take a shot. Early one sunny morning, when a warm wind rippled across the seas of golden wheat, I did manage to get close enough to line up some sparrows perched in the hedgerow in my sights. But in the breeze they swayed so much that when I fired I missed. While her feathers were still growing, I needed to feed Kes three times a day on sparrows or starlings, as any shortage of natural food could temporarily stop proper feather growth and leave “hunger traces”, which look like razor cuts across the feathers, making them liable to break. I continued to stalk the hedgerows but didn't manage to shoot a bird before going to work.

Two weeks or so later, at around 11pm, I could just make out the rectangular bales of straw in the field. Under my boots I could feel the stiff, sharp stalks of stubble as I walked through the recently harvested wheat. Opening a gate at the edge, I entered my brother's garden. Untrained hawks are calmer in the dark and I'd come to check if Kes's feathers had stopped growing.

I switched on my torch, throwing shadows around the corrugated-iron walls of the mews. In the half-light Kes remained calm and, carefully fanning out her tail, I shone my torch on the bases of the feathers. A few nights earlier the shafts of the feathers had been soft and blue, still “in the blood”, but tonight I saw what I so desperately wanted to see: the shafts of the feathers were hard. She was ready to train.

I switched off the torch and could just make out the baking scales I'd commandeered from my mother, which were standing on the floor in a corner of the mews. I stood the scales on the shelf perch I'd fixed behind the door, then, pulling on my “gauntlet” – a gardening glove – I walked back to Kes standing on her perch, the dark making her as docile as if she'd been drugged. I touched the back of her legs. I'm not sure why, maybe the pressure on the back of the legs makes a hawk feel slightly unbalanced – but just as my falconry book had suggested Kes stepped back on to my glove. Carefully taking hold of her jesses in my gloved fingers, I carried her across the mews, gently pressed the back of her legs against the wooden perch I'd fixed on to the baking scales, and persuaded her to step backwards onto them. I shone the torch on the dial and saw the pointer had stopped just short of nine ounces.

I knew from my reading that I'd need to bring her down to a “flying weight” of around eight ounces by reducing her meals from three to one a day – and at this weight, in the words of the 17th-century falconer Symon Latham, she would “flie with spirit, courage and attention to the man”...

'No Way But Gentlenesse', a memoir by Richard Hines (Bloomsbury, £14.99), will be published on 10 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments