The mother of lost children: The truth about wartime heroine Edith Cavell

Edith Cavell was the Florence Nightingale of the First World War. Her biographer, Diana Souhami, explains why she had to give up the search for a character flaw

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There is a statue of Edith Cavell in St Martin's Place in central London. Hewn from a block of granite, she stands 10ft high in her matron's uniform, under the words "For King and Country". At her feet is carved her name, and the hour and place of her death: "Dawn. Brussels. October 12th 1915." A little while after its unveiling, the words she spoke on the eve of her execution were added: "I realise that patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone." The inscriptions are confusing: the rallying cry on the apex belies the very different, soul-searching words on the plinth.

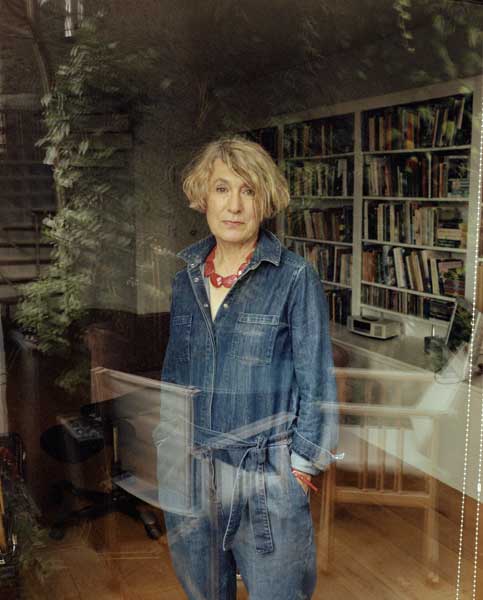

Walking, as she often does, towards the English National Opera, Diana Souhami began to wonder about the figure standing so tall and serene at the crossroads. A prize-winning biographer, Souhami had decided that her next book should be about altruism. Few people, she realised, exemplified this virtue as convincingly as did Edith Cavell.

Talking about it now, in her bright, sunny flat high up in the Barbican, she worries that her book might be seen as hagiography. But what was to be done? "She was entirely driven by altruism: it was the very essence of her being. Usually, when I start research, I find out all kinds of horrible things about my subject. It's useful for a biographer, in fact; it gives a more rounded picture. But really, I couldn't fault her. There's simply no avoiding it. She was always thinking of others, right up to the very end of her life."

Born at the end of 1865, the daughter of a Norfolk vicar, Cavell was brought up with a sense of duty to share whatever she had, to help those in pain, to alleviate suffering. "From the day of her birth," Souhami writes, "the Christian command of love was her moral standard."

She became, inevitably, a governess – still one of the only professions available to such girls. Sent to Brussels to look after the children of a prosperous lawyer, she learnt French and discovered a wider world and ambitions of her own. She decided to become a nurse and took a job at the Fever Hospital in Tooting, before being accepted for formal training at the London Hospital, under the formidable Eva Luckes.

Souhami's research is impressive, and seen throughout this powerfully gripping, elegantly written and astonishingly detailed book. She studied, for example, Cavell's hospital notebooks. Here, Cavell conscientiously recorded the details of her training, including the various forms of pain relief available. These were, apparently, cocaine, morphine and – rather marvellously – champagne: "Not a lot has changed," Souhami smiles. Cavell also learnt how to perform tracheotomies and how to lay out the dead with proper respect, a dignity she herself was to be denied.

Once qualified, she undertook demanding jobs in London's St Pancras and Shore-ditch infirmaries until 1907, when an offer came to set up the first hospital in Brussels. It was a stupendous challenge, to which she rose with poise. Within the eight years left to her, she established a gold-standard hospital and was well on the way to opening a new, purpose-built nurses' school.

Then came the war. Cavell was in Norfolk with her widowed mother when it broke out. She hurried back to Brussels, hoping that, like Florence Nightingale, she would be able to help wounded soldiers. But she was not prepared for the shock of seeing the invading army marching into Belgium. "Nothing," says her biographer, "not all her years of working in the slums of the East End, gave her so much grief as seeing that proud people so humiliated."

Nor was she able to offer much help to wounded soldiers. "She didn't care where her patients came from," says Souhami. "As she told her nurses, each man was a father, a husband, a son: the profession of nursing knew no frontiers." However, after the first few weeks, the Germans set up their own hospitals for their wounded; Allied soldiers were taken to a Red Cross hospital and then transferred – however badly hurt – as prisoners of war to Germany.

But now, the enfants perdus began to be brought to her door. These were wounded men left behind after battle, terrified and traumatised, hiding in the woods. Cavell took them in, looked after them and found ways of getting them to the Dutch border and safety.

This was her "crime". As their numbers increased, it became harder to hide them, and as they recovered, they tended to become rowdy. Unable to discipline them as she would have liked, for their own safety she would carry on with her normal, public work, giving lectures to her nurses, looking after

her bona fide patients, and busily preparing the new school. When German forces raided the hospital, she hid the men wherever she could, in beds, in the garden, even popping one of them into a barrel and covering him with apples.

When it was safe, she would go for an evening walk with her dog Jack, a bad-tempered mongrel who had also simply arrived at her door and been taken in (and who now stands, stuffed, in the Imperial War Museum). Behind them, the wounded soldiers would walk, often bizarrely disguised, toward a rendezvous where a guide would meet them and help them across the border.

Cavell wasn't concerned with what happened to them when they left her care. She simply wanted to see them safe. But the occupying forces disagreed, and the net was closing in. To her deputy she said, "If we are arrested we shall be punished in any case, whether we have done much or little. So let us go ahead and save as many as possible of these unfortunate men."

In the event, she was accused of sending enemy soldiers back to their lines. Taking her oath seriously, she said nothing to save herself, though she was careful to incriminate nobody else. She was tried in German, which she didn't understand, sentenced one afternoon and executed the next morning. During that last night, she read a book she had always loved, The Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis. She marked several passages. One reads: "Vanity it is, to wish to live long, and to be careless to live well." Her compassion was profound and her integrity inviolable. When offered the services of her own pastor at her execution, she refused. "No," she said, "Mr Gahan is not used to such things."

After her death, a storm of protest gathered and broke noisily across the world. The propaganda effect was formidable and her fame spread like an epidemic. (One baby, born two months later in a French slum and given her name, became famous in her own right, as Edith Piaf.) It was said that her execution doubled recruitment to the Allied cause and even destabilised American neutrality. As H Rider Haggard remarked, "Emperor Wilhelm would have done better to lose an entire army corps than to butcher Miss Cavell."

When her body was eventually exhumed in March 1919, it was incorrupt. A comb, a collar-stud and a hat-pin were retrieved from her grave and polished up, as relics, and a grand funeral arranged. Diana Souhami is still angry on her behalf: "She didn't want that! She wanted to live, and to carry on her work. What she needed was a good lawyer, someone prepared to pick up a phone and protest. But all of the influential men were busy, or preoccupied."

It is achingly sad. But Diana Souhami insists that Edith Cavell's is, ultimately, an uplifting story. She quotes from Richard Lovelace's 1642 poem "Stone walls do not a prison make...". And she adds, "Edith Cavell was never prim, never old-maidish. She gathered around her a rather modern 'family' of needy individuals, headed by the naughty Jack – who would round up the young nurses like sheep, snapping at their heels. And she was incapable of being a victim. Courage isn't the word for it: to be brave you have to be afraid; I'm not sure she was ever afraid. I am not religious, but I think we all recognise genuine goodness when we see it. She was unswerving, her moral compass fixed. And she had a nobility of sprit that couldn't be silenced. In a way, she couldn't even be killed."

The extract

Edith Cavell, By Diana Souhami (Quercus £25)

'...She had disguised Allied soldiers as monks, assigned false medical papers and passports to them, denied their existence, but that was all to save their lives, not her own. If these officials with bayonets and guns, whose uniform she despised, who to her thinking were complicit in heinous crimes... if they wished to parade their cunning in indicting her, so be it... She was not going to dance to their tune'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments