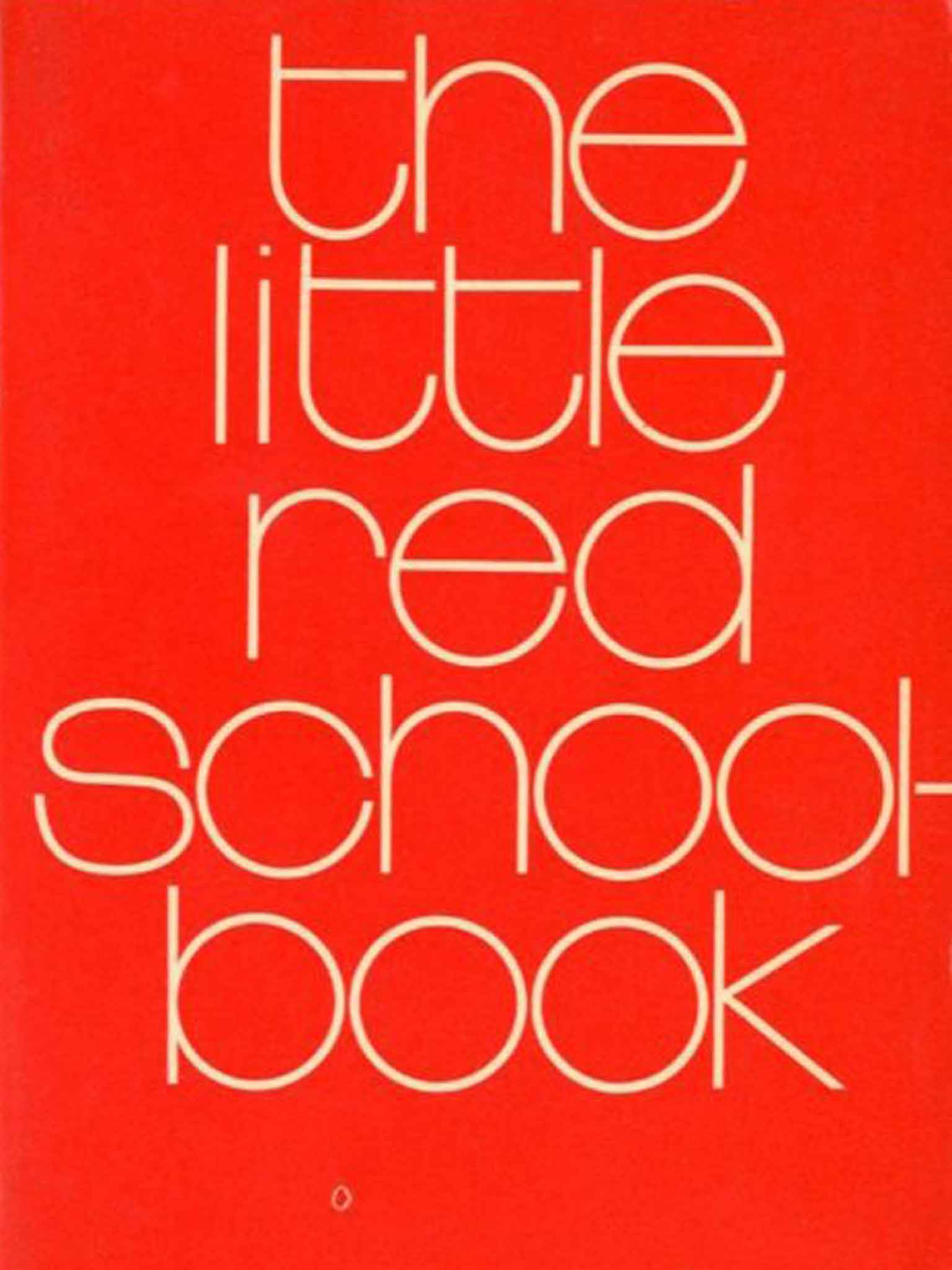

The Little Red Schoolbook: A handbook for under-age revolution?

Sex, drugs and how to assert their rights at school... advice to children in a 1960s book caused global outrage. Now it’s to be reissued with the ‘naughty’ bits back in, says Andy McSmith

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Was there ever a more misnamed decade than the Swinging Sixties? While a few university students were having a high old time on dope and rock’n’roll, most people in the advanced Western world were stuck in the mental prism of post-war austerity. Just how prurient and respectful of authority people were back then is well illustrated by a decision to reissue The Little Red Schoolbook, which caused a global scandal at its first appearance, in 1969.

To read it is to revisit an experience I had last year as I struggled to the last chapter of D H Lawrence’s novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover, which was the subject of a sensational trial in 1960: you read on and on, expecting to reach the bit that caused the fuss, and eventually realise you have gone past it. If The Little Red Schoolbook’s Danish authors, Soren Hansen and Jesper Jensen, deserved to be prosecuted, it is for the blatantly false use of the word “Little”. There are classic novels shorter than this long treatise on what children should be allowed to know.

The problem at the time, obviously, was that any schoolchild who got hold of the book was inevitably going to skip past the first 100 pages of left-wing pedagogical theory to go to the well-thumbed section on sex, where he or should would find words that even now would not usually appear in a family newspaper without the use of asterisks. In that section, a child could read that “if anybody tells you it’s harmful to masturbate, they’re lying”.

There was also advice on how to enjoy sex without causing an unwanted pregnancy, while young women who did become pregnant could read about the practicalities and hazards of an abortion. And there was an optimistic forecast that “the time will come when homosexual marriages are recognised”, which in this country took more than four decades to come true. Finally, there is a section on pornography with which the surviving author, Soren Hansen, is obviously not comfortable any more. The message was that it is “harmless” but should not be mistaken for reality.

At the end, the authors delivered some sensible advice about drug abuse, which caused some controversy at the ti me simply because alcohol and tobacco were discussed under the same heading as cannabis. The much longer and much less-often-read section on teaching is actually the more controversial. The authors acknowledged that state-school teachers did not have an enviable lot: they were low paid, were expected to work outside classroom hours for no extra pay, and had little choice about what they taught or how they taught it. There were schools where women teachers were banned from wearing trousers, or where “teachers have to go outside the school premises if they want to have a pee”.

But the general thesis is that children’s natural curiousity and eagerness to learn were in danger of being stifled by dreary, authoritarian teaching methods. “Remember that everything you’ve learnt, you’ve learnt yourself. You have to do the work of learning. Your teacher can’t do it for you,” the book proclaims.

Support the teacher who makes the lesson interesting, but subvert the one whom you find boring was the message. “Mucking about” is a “natural reaction” to boredom. However, “Never muck about unless you’re absolutely certain that the teacher is an incurable bore”.

There was a list of suggested ways to muck about, including drawing on the cover of school books, making paper planes under the desk, passing notes to other pupils, or “reading comics, thrillers or pornographic magazines under your desk”. Fortunately, the section is so long that any child with the self-discipline to read it probably was as self-motivated as the authors assumed.

First time around, The Little Red Schoolbook was banned in France and Italy. In Australia, its publication caused such an outcry that it was feared it might cost the Liberal government the 1972 election. In the UK, the Home Secretary, Reginald Maudling, and the Education Secretary, Margaret Thatcher, were under pressure from Tory MPs to ban it but took refuge in the line that dealing with obscene publications was a matter for the police.

The second time around, the book is unlikely to be read as a handbook for under-age revolution, but instead as a historical curiosity.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments