The Big Question: Has the time come to close the book on women-only literary prizes?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

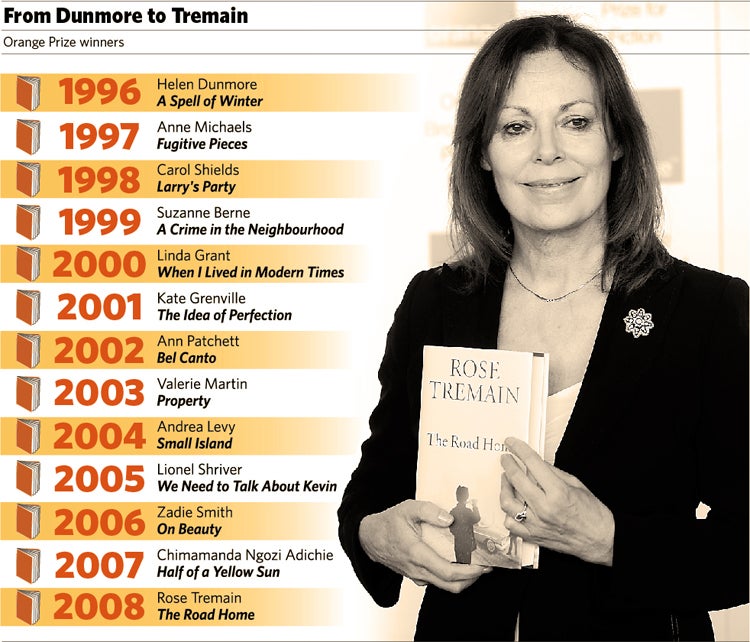

The Orange Broadband Prize for Fiction was presented at a typically ebullient ceremony at the Royal Festival Hall on Wednesday. As predicted by the bookies, Rose Tremain won the women's fiction prize for her "very warm and empathetic" tale of immigrant life, The Road Home, and in a reference to the award's (mainly) male critics, said: "Come on guys, stop grumping!"

Presenting the award, the chair of the judges Kirsty Lang said that it was particularly deserved because Tremain "is one of our greatest contemporary authors and has been overlooked by the literary establishment". The Road Home was shortlisted for last year's Costa Book Award but didn't win.

What else did Ms Tremain say?

"This is a prize which celebrates women's fiction. In this year when A L Kennedy has won the Costa, when Anne Enright has won the Booker and when Doris Lessing has won the Nobel, I think there's a lot to celebrate." Tremain did not name names, but the "grumping" she referred to has been especially querulous this year.

And the judges?

Lang denied that the Orange is a form of positive discrimination, arguing that it has done much to attract readers and highlight novels that would otherwise be overlooked. She did admit that among the 120 entries there was "a lot of dross". "If they haven't had the unhappy childhood, then they make one up. Lots of grim child sex abuse." She had previously said: "The Orange has now become a celebration of female writing. It would be pointless to stop the prize because it has done what it set out to do." The other judges were Lisa Allardice, Philippa Gregory and Bel Mooney – Lily Allen having dropped out citing personal problems.

So what's the perceived problem with the Orange?

That limiting the prize to women writers is unfair and anachronistic, according to its most recent critics. The latest round of debate was kicked off in March by the writer Tim Lott, who called the prize "a sexist con-trick". "Could the establishment of a men-only prize be justified?" he asked. "Can you imagine the derision with which it would rightly be met?" He concluded that "the Orange Prize is sexist and discriminatory, and it should be shunned".

Who are the main critics of the prize?

Largely speaking, men. And Lott's comments are nothing new. When the Orange was founded, Auberon Waugh nicknamed it the Lemon Prize. The academic John Sutherland claimed that it does women writers more harm than good. Alain de Botton asked: "What is it about being a woman that is particularly under threat, in need of attention, or indeed distinctive from being a man when it comes to picking up a pen?" And Derek McGovern recently wrote in The Mirror: "The Orange Prize for Fiction has always annoyed me because it is open only to women – surely it should be called the Chocolate Orange Prize. I have to say I've never rated women novelists."

But the disapproval is not limited to men. A S Byatt claimed that the prize "ghettoised" women, and recently revealed that she has forbidden her publisher from entering her books. Germaine Greer and Anita Brookner are also critics.

So what is the justification forall-women prizes?

The novelist Kate Mosse, who co-founded the prize, said: "The prize was set up to celebrate international fiction written by women and to get fabulous books by women to male and female readers and it continues to be really successful in doing that." Part of its raison d'être was to encourage women's writing at a time when it seemed to be largely ignored by the larger prizes. However, five of the last six Whitbread/ Costas and the latest Man Booker prize were won by women.

Shouldn't the prize at least allow men to be judges?

"I'm open-minded about it," said Lang last week. "It would be an interesting debate for organisers to have. Seventy per cent of fiction is bought by women, so having a panel of women judges means they know what women like. But I think it could be quite interesting to have a man on the panel." In 2001, the organisers asked an all-male "shadow jury" to consider the long-listed books. They chose the same winner: Kate Grenville's The Idea of Perfection.

Why isn't there a men-only prize?

"Because no one has, as yet, put in the time, creativity, effort and enthusiasm necessary to start one up and keep it going," said the Orange Prize's website. The critic Erica Wagner agreed: "Nobody can do anything about that until somebody puts his money where his mouth is and launches a lads-only prize."

The novelist Nick Hornby said: "The controversy around the Orange Prize is entirely bogus. You might just as well complain that Roger Federer isn't allowed to enter the Grand National." The writer Susan Hill has joked that she is to sponsor a new prize "for a novel written by anyone who was born before 1988 in Budleigh Salterton and who is an only child... [People] can have a prize for whatever they damn well like."

What's the history of the Orange Prize?

The prize was partly inspired by France's Prix Femina, which has existed since 1904. It was announced at the ICA in January 1996 and awarded to Helen Dunmore that May for A Spell of Winter. Later, Orange Futures named 21 authors to watch in the new millennium. On its 10th anniversary in 2005 the Orange Broadband Award for New Writers was established and a "Best of the Best" was awarded to Andrea Levy for Small Island, though she has recently admitted that she felt uncomfortable about the "best of" concept.

Does 'women's fiction' still mean anything in modern publishing?

Last year, the judge Muriel Gray caused some controversy when she complained that much of the fiction submitted was on domestic themes. She was not as dismissive, however, as Paul Bailey, chairman of the 2001 men's jury, who said that "the only difference [between the juries] was we didn't go for famous names or books banging on about breast cancer, mothers and daughters - we've had all that up to our eyeballs."

Is there still a place for all-women prizes?

Yes...

* There's nothing wrong with celebrating women's fiction – men could do the same if they wanted

* The Orange is an international prize which brings attention to otherwise overlooked literature

* Historically there is still a tendency for the bigger prizes to employ male judges and choose male winners

No...

* Other overlooked groups include working-class authors, disabled writers, black African writers... there are no prizes for them

* It ghettoises women's writing, patronises women and encourages separation and discrimination

* Writers, readers and publishers are overwhelmingly women anyway. Boys, not girls, need to be encouraged to read

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments