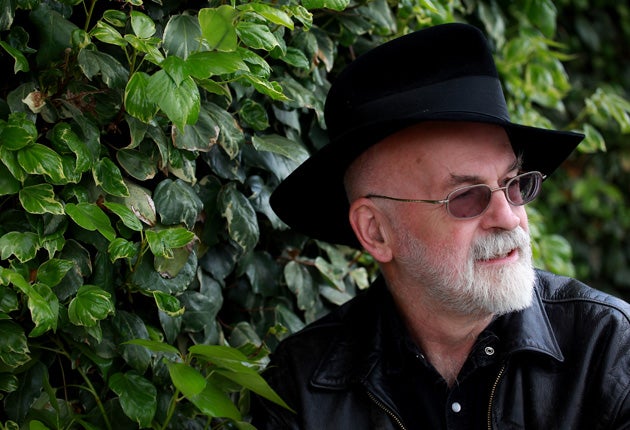

Terry Pratchett: My brush with Death

A tsunami leaves a boy dealing with the trauma of burying his people in Terry Pratchett's latest Carnegie-shortlisted novel – a book he says he's been preparing to write all his life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Terry Pratchett is sipping on a "ferocious" Bloody Mary and musing on God, Wyatt Earp and how Neanderthal man mourned his dead, when I throw the really big question at him. "Ha!" he exclaims. "Now we come to it," and proceeds to dodge the issue of the prestigious Carnegie Medal for Children's Literature, and whether it would mean a lot for him to win it a second time.

"I have been shortlisted three times; this is the third. I will not win this one. I am prepared to guarantee it. There are very few people who have won the Carnegie twice... practically none," he doesn't answer.

He seems to be preparing himself for disappointment, which suggests that it would mean a lot. Not that there's anything falsely modest about the softly spoken Sir Terry. Remind him that he has sold more than 50 million books, and he is quick to point out that, actually, it's 65 million.

Pratchett is best known, of course, as the creator of Discworld – a riotous universe of apprentice witches, wizards, thieves, postmen, journalists, detectives and monks. Set on a flat world supported by four elephants standing atop a turtle, Discworld and its attendant books are a satire on modernity that has made Pratchett one of the bestselling authors alive. He has now been shortlisted for the Carnegie Medal for a non- Discworld book, however. Nation, published in 2008 (this year's award catchment runs from August 2008-September 2009), is an extraordinarily complicated tale about God, tradition and loss. Yet it is told with beautiful simplicity and rollicking readability.

It is about a boy called Mau who lives on an island in the Pelagic Ocean in a parallel universe (that great gift to the modern author from theoretical physics) that is very similar to our own 19th century. He is on the cusp of manhood when his people are washed away by a tsunami. The only other person alive on his island is a girl of the same age, the feisty Daphne, whose ship from Britain was dumped in the middle of a rainforest there by the enormous wave. The book is at once a coming-of-age drama and an adventure tale, but also a cornucopia of just plain interesting things.

We are sitting in a country pub near Pratchett's Wiltshire home, a fitting place to interview a man with an enormous reservoir of facts and opinions about philosophy, history, science and, well, you name it, at his fingertips; as well as the ready wit so often found in his books. "I think what happens is you go through life and pick up all kinds of stuff subconsciously from reading, and suddenly it all turns up when you want it," he says of Nation. "Whenever I wanted something I put out my hand and it was there. I did do some research, but I've been doing an awful lot of the research since I was a kid, like reading books on the Pacific."

The core of the book is how Mau holds together the traditions of the past while rebuilding for the future. The scene where he single-handedly gives the dead their traditional burial at sea is truly harrowing.

"Nation was one that I'd have killed myself if I hadn't written it," Pratchett says. "It was absolutely important to me that I wrote it. It was good for my soul." It was published two years before the recent death of his mother. Her funeral illustrated deeply for him the desire to honour ancestors. "I never felt so bad as on the day she died and the day of the funeral," he says. "We know that Neanderthal man actually buried the dead offering flowers, and frankly I don't think Neanderthals had a sophisticated religion going for them. So the things we do go back to when we were only just becoming human beings. The idea that you bury and commemorate the dead is absolutely ancient."

There is also Pratchett's pet theme in the novel: the conflict between science and religion. Or rather, God and rationalism. Mau rages at his gods for letting the disaster happen, denies their existence, yet hears them and is, to some extent, afraid of them.

"Why does God let this happen to good people?" asks Pratchett. "I got quite annoyed after the Haiti earthquake. A baby was taken from the wreckage and people said it was a miracle. It would have been a miracle had God stopped the earthquake. More wonderful was that a load of evolved monkeys got together to save the life of a child that wasn't theirs."

Pratchett has an ongoing obsession with God – or rather the lack of one – and Death, who is often present as a character in his work. In Nation he is there in the form of Locaha, the god of death, who tempts Mau by opening up the pathway to the perfect world. Mau turns him down, telling him that he'd rather create a perfect world on Earth.

"Neither of my parents went to church but they did everything that you needed to do to be Christian," Pratchett continues. "That's something a Quaker would call an intimation of the divine. To be frank, what buggers up the whole thing is the Old Testament. Christ managed to boil down an awful lot of commandments to a few very simple rules for living. It's when you go backwards through the begats and the Garden of Eden, and you start thinking, 'Hang on, that's a big punishment for eating one lousy apple... There's a human-rights issue.'"

Pratchett adds that the author's job is to tap into the "common humanity" which holds us all together. But there is something else he's identified: the need to hold on to the past before it falls through our collective fingers. "One of the things that intrigues me is that the past is so close. I might call my autobiography My Dad Could Have Shaken Hands with Wyatt Earp. My dad was nine years old when Earp died, and he's a historical character."

A favourite of Pratchett's own books is Johnny and the Dead, about a boy who makes friends with the spirits of a graveyard. He got the idea when, while working as a journalist, he covered the opening of a British Legion building by a man called Tommy Atkins – the generic name given to soldiers in the First World War. "I went back into an office full of putative adults who asked: 'Tommy Atkins, who's he?' And I thought, 'This is a bit of history that's floating away.'"

Pratchett, who has a grown-up daughter, Rhianna, lives in a place where mobile phones don't work and there is nothing much apart from sheep and misshapen trees. It is the sort of idyllic, hillocky landscape you can imagine Discworld to be. And Pratchett, in his trademark black fedora, is every inch the local squire of an inverted world. He was born in 1948 and began his working life on local papers before joining the electricity board as a press officer. His first book was published in 1971, and his first Discworld book, The Colour of Magic, in 1983. He didn't become a full-time writer until 1987, however, when he was 39.

In the past few years he has become famous for something else. He is, at 62, a celebrity Alzheimer's sufferer. His is a rare strain, posterior cortical atrophy, which initially affects motor skill. His diagnosis has been well documented, yet listening to the ideas, metaphors and one-liners tumble out of him, it is hard to guess he is suffering from a brain disorder. "It kind of embarrasses me that I've become the Alzheimer's spokesman, yet there is me walking around, chatting with people for hours on end. But the endgame is going to be the same for everyone with dementia."

It is rare for an author to enjoy both large sales and literary acclaim, and Pratchett, as a science-fantasy children's author, has long felt the stare of snooty disdain coming down the noses of the literary establishment. Hence his pleasure at his OBE in 1998, his knighthood in 2009, and his chuffedness at being shortlisted for another Carnegie. For all his pointed lack of expectation, however, Pratchett knows where real recognition lies: in "queues going down the length of the street.

"Not that I write for the money. I write for the satisfaction of a job well done. I was very pleased with the knighthood. If only my dad had been alive, that would have been a massive thing. My dad was a motor mechanic; my granddad was a gardener; my great grandfather, who I never met, was a farrier. So here's to you guys," he says, and lifts his glass to the dead, the past, the ancestors and tradition.

The extract

Nation, By Terry Pratchett Corgi £6.99

'... The sand under Mau's feet turned black, and there was darkness on every side. But in front was a pathway of glittering stars. Mau stopped and said, "No. Not another trap."

But this is the way to the perfect world, said Locaha. Only a few have seen this path!

Mau turned around. "I think if Imo wants a perfect world, he wants it down here," he said'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments