Sunjeev Sahota interview: Rise and rise of the Man Booker shortlisted author

No one was more surprised at making the Man Booker shortlist than Sunjeev Sahota. But then he only read his first novel at the age of 18. Andrew McMillan meets a literary sensation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sunjeev Sahota opens the door to me early on a Friday afternoon with an air of anxiety, as though I was arriving to ask him to sit a test, rather than interview him. He invites me in and, after making sure that I don't need a cup of tea, we sit at opposing ends of the large sofa in his living room, like a couple come home to meet the parents.

He has a controlled, quiet voice, as though permanently trying to quell an argument. When we meet in the house he has just moved to in Sheffield – he previously lived in Chesterfield – he sits quite rigidly, as if stiffened by nerves.

He is not necessarily what you expect from one of the coming men of British literature. Something confirmed when we start talking about how he writes. He does so, he says, with "the curtains closed" and "without any natural light". Soon he will be doing so in the basement study of his new house. I ask why and he gives a response which astounds me . He does not want, he says, "to be caught in the act of something that feels illicit".

That pressing shyness, his reluctance to share himself, might explain why he might well be the best author you've never heard of.

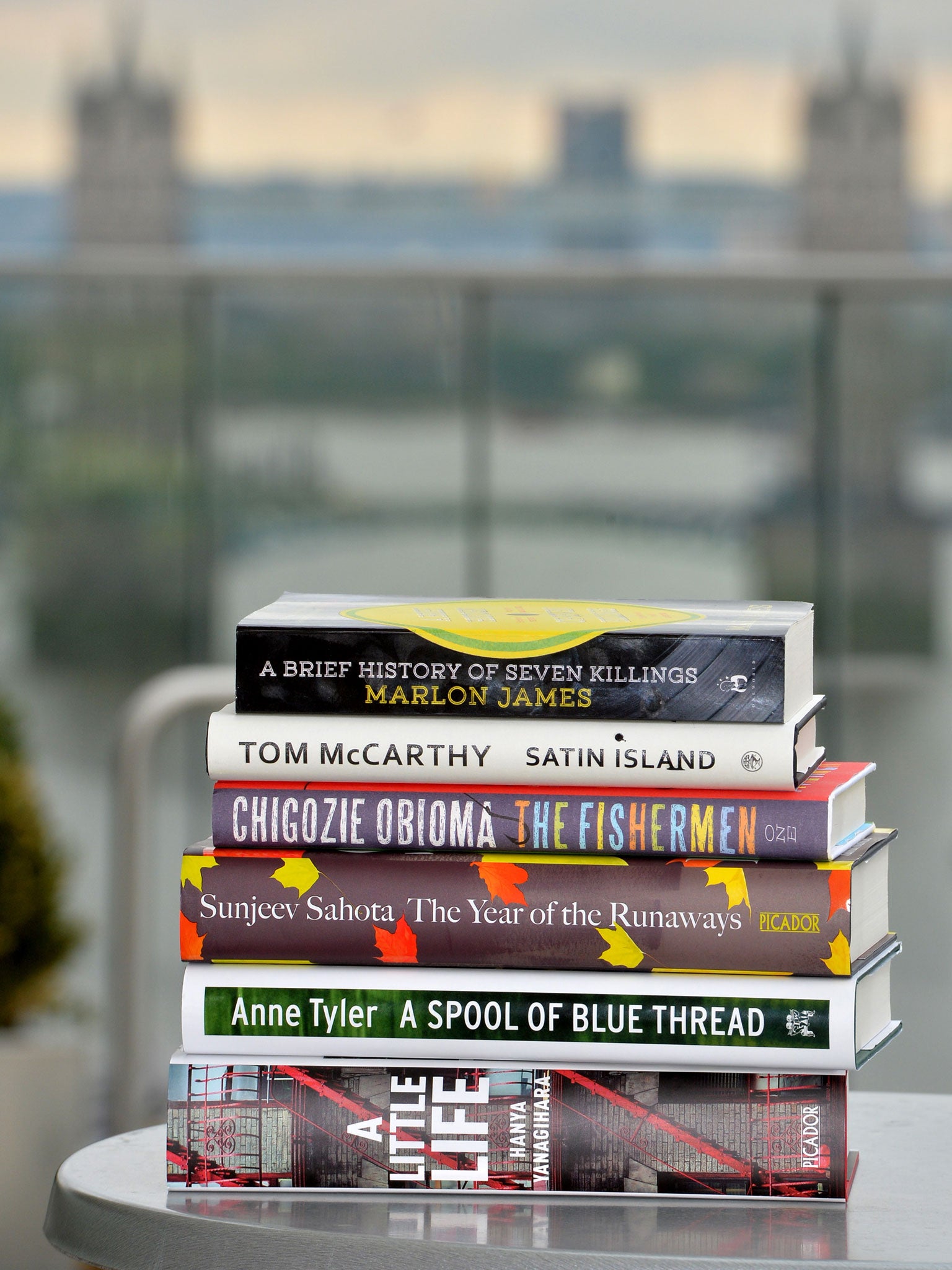

Four days after our meeting, Sahota’s second book, The Year of the Runaways, is one of the six that make it on to the shortlist for the Man Booker prize. He will be competing against Anne Tyler, Hanya Yanagihara, Chigozie Obioma, Tom McCarthy and Marlon James for the £50,000 prize and more publicity than he is possibly prepared for. Sahota tells me he’s previously used the list to decide what he should be reading.

That is by no means his only accolade, either. In 2013, an early section of his book was submitted by his agent to the king-making Granta Under-40 list in. It hit the mark and Sahota immediately joined the ranks of Granta young novelists, which have included, among others, Martin Amis, Alan Hollinghurst and Will Self.

The book was hailed by Granta's then-editor, as "like his ninth novel, it's such a huge leap forward".

Sahota tells the story of getting the news in the understated manner that comes to mark our time together. "I knew my agent had submitted me, but I didn't expect to hear anything". His daughter was born on 2 January 2013 and five days later he got a phone call from Granta's editor telling him he'd been selected. What did he do when he heard? "I stood up from the settee," he replies. His response to being told he was on the Booker list was similarly calm. I suspect fellow Picador author and Booker shortlistee, Hanya Yangihara, who has been doing the rounds of popular talk shows in the US to promote her work, may have had a slightly rather stronger response.

Even the presence of a Salman Rushdie quote on Sahota's new hardback ("All you can do is surrender, happily, to its power") he describes simply as "feeling like it had come full circle". What Sahota means is that Rushdie's Midnight's Children – another former shortlistee and, indeed, winner of the Booker prize – was the first novel he ever read, when he found it in an airport bookshop while on his way to India. His age at the time? 18.

Sixteen years later, Salman is endorsing Sahota's second novel. I suggest that is enough to turn any author's head. Sahota looks worried, and quickly makes clear he doesn't see himself "of that stature".

I ask him if he aspires to be both a public and literary figure, in the same way Rushdie is. "I don't aspire to be a public figure," he says and goes on to suggest Rushdie was "forced into that position" because of the fatwa placed on him by Ayatollah Khomeini after the publishing of The Satanic Verses. "I want to be a great writer, first and foremost". He does qualify this a bit, though: "If there are topics I feel strongly about, issues I could lend my support to" then he says he would; that he "doesn't want to shy away from a cause or institution". Having lived "a relatively privileged life", he feels "a responsibility to do my bit, my part". Certainly he shares some characteristics with Rushdie, though he is unlikely to be caught, as Salman once was, on The One Show playing table tennis against an automated machine while answering "Would You Rather" questions. He wants, he says, the work to speak for itself.

His first novel Ours are the Streets, came out in 2011. It follows Imtiaz Raina, a disaffected young Muslim who is radicalised when he travels to Pakistan and returns with a plan to blow up a prominent site in Sheffield. The novel drew on a current affairs zeitgeist, but what was perhaps more interesting was its refusal to condemn its central character, who was portrayed as alienated, rather than evil. The Independent's literary editor, Arifa Akbar, pointed out the novel's unexpected shift into a story of "psychopathology and emotional meltdown, rather than one of religious fanaticism".

The Year of the Runaways, is similarly of the moment, concerned as it is with refugees and migrants making their way to the UK. The book focuses on four central characters, three young men from different backgrounds who, for different reasons, make the journey illegally from India to England in search of work and a better life. In this they are helped by a young woman born in England called Narinder, whose neatly planned life begins to unravel as a consequence.

There's a tone of sincere morality throughout the book. Does Sahota see his novels as having a responsibility to the people he's writing about? There's a long pause before he replies, "The ultimate responsibility", he says "is to the truth, there's nothing else, everything else is in service to the truth". Truthful how? "Truthful to the world". He feels he has a "responsibility to their stories", to avoid the "danger of being irresponsible, of being sensationalist". He is much more confident speaking of his writing self looking outwards, rather than about the world looking in at him.

The writer’s ultimate responsibility is to the truth. There is nothing else

Still, he certainly doesn't shy away from difficult topics in his work. For instance, Sahota insists that the stories "always have a personal start". In the case of Ours are the Streets, one of the 7/7 bombers came from near where Sahota lived in Leeds and it led him to wonder "what could make someone like me" do something like that.

"A few people wondered why" a Sikh might want to take on issues of Islamic radicalisation he admits. But, he adds, people mainly responded with "thoughtful" comments. Ultimately he felt that the 7/7 bomber who came from Leeds had begun life "like me", had had the same "sorts of feelings of not belonging".

The personal start for The Year of the Runaways was the stories he heard from young men when he travelled over to India, as he does once or twice a year. When he's first saying this, he stumbles slightly, saying "back to India", before stopping himself. He seems interested in that accidental slippage "It's closer to me than the news" he says.

Sahota's grandparents emigrated from the Punjaab in 1966. They settled in the Normanton area of Derbyshire in the mid-to-late 1960s. His grandfather took a job in an iron foundry in Derby, the town where Sahota was born in 1981. He then moved to Chesterfield when he was seven. He still, he tells me, feels like he "has a foot in both cultures".

For a while he lived in London when studying maths at Imperial College, which he tells me was an antidote to the "lonely experience of growing up" in Chesterfield. Whereas in Derby he'd felt comfortable in his "own community" of Sikhs "all from a particular historical caste group", once in Chesterfield he found himself interacting only with "White English people or people in my own family". He tells me he felt "conspicuous" in Chesterfield. Sahota and his brother, were "the only brown kids there" in school. Whereas London was the "first time in England I felt like part of the everyday wallpaper of life" which enabled him to "reflect on the childhood" he'd had. While he was born in England, he says he felt many people were "not from the same place, internally" as him

Why then, did he leave London, which, like it or not, is also the literary centre of Britain, as well as where he spent his university days? "Family is crucial", he fires back. His parents live in the north, running the same shop in Chesterfield they've had for more than 30 years. Sahota's wife crosses the Pennines to work for Transport for Greater Manchester each day. The north is where, after four years in London, Sahota felt he was called back to. This perhaps explains whey Sheffield found itself as a central character in both of his novels.

Humble as he may personally be, he has an absolute idea of what novels can achieve. What he wants, ultimately, he says, is to give the characters in his novels a "completeness". "If novels can do anything", he says, "it is shining a light into that dark tunnel, faces, histories, stories". By showing the characters in The Year of the Runaways in their "completeness", their illegal journeys into England, their loves, their day-to-day struggles and joys, he is illuminating a path for other people making that journey, as well as his characters. "How could you deny them their stories?" He is at his most animated when he is talking about his work.

When the photographer arrives, he is back to the shy Sahota who first opened the door, a writer not yet at home with the type of attention he is about to receive. I ask him if it feels odd, this kind of scrutiny. "This is the first time we've had people come to the house" he says. And later, when the photographer sets up a mini-studio in the kitchen his discomfort is palpable.

At one point, the photographer suggests he might get a shot of Sahota out on the street. There's a momentary look of horror on Sahota's face. He quickly says that perhaps they could try somewhere further out – on Ecclesall Road, which happens to be one of the streets which feature in his books.

One journey Sunjeev Sahota can't illuminate with his work is the future path of his own life. One thing is certain though, the lights on him are only likely to grow brighter.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments