Steven Pinker: 'Artists used to gush about the beauty of war. The First World War put an end to that'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

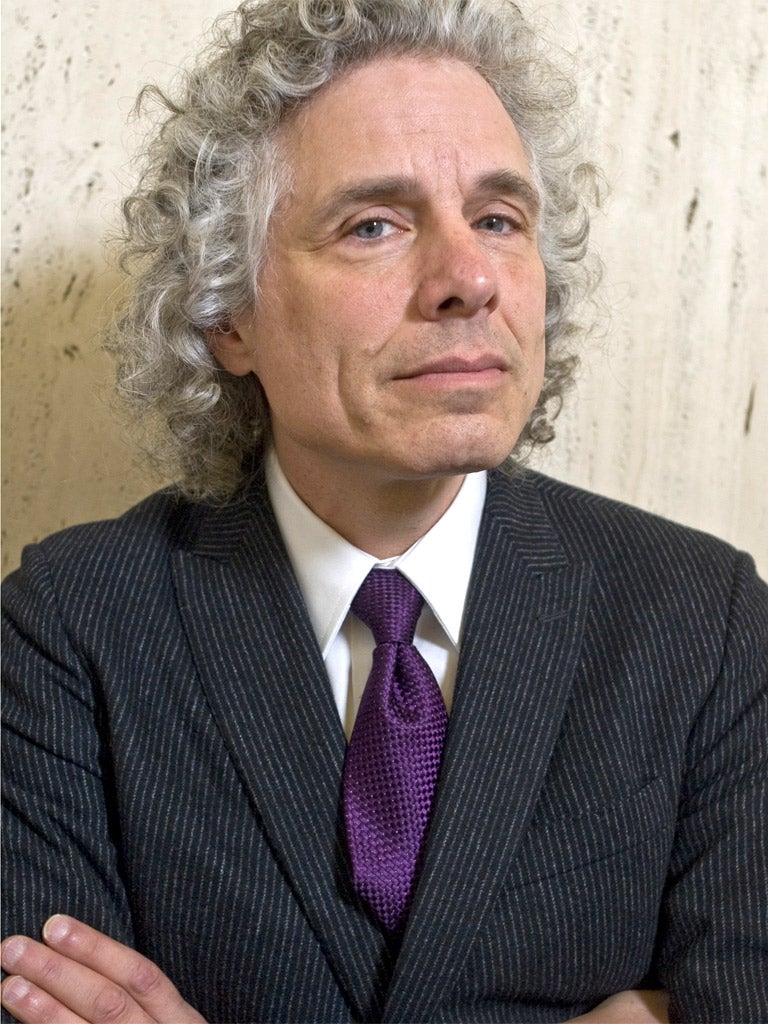

Your support makes all the difference.Steven Pinker is the Johnstone Family Professor in the psychology department at Harvard University. This newspaper said of his work that "words can hardly do justice to the superlative range and liveliness of Pinker's investigations". His latest book The Better Angels of Our Nature argues that humans have never been less violent than we are now. Clint Witchalls asked him to explain.

Clint Witchalls: You say that, over the centuries, violence has been declining, yet most people would view the last century, with its pogroms, death camps and nuclear bombs, as the most violent century. Why was it not?

Steven Pinker: You can't say that a particular century was the most violent one in history unless you compare it with other centuries.

The supposedly peaceful 19th century had one of the most destructive conflicts in European history (the Napoleonic Wars, with 4 million deaths), the most destructive civil war in history (the Taiping Rebellion in China, with 20 million), the most destructive war in American history (the Civil War, with 650,000), the conquests of Shaka Zulu in southern Africa (1-2 million), the most proportionally destructive interstate war in history (the war of the Triple Alliance in Paraguay, which killed perhaps 60 per cent of the population), slave-raiding wars in Africa (part of a slave trade that killed 37 million people), and imperial and colonial wars in Africa, Asia and the Americas whose death tolls are impossible to estimate. Also, while the Second World War was the most destructive event in human history if you count the absolute number of deaths, if instead you count the proportion of the world's population that was killed, it only comes in at ninth place among history's worst atrocities.

I think few people would disagree that the medieval times were tortuous and bloody, yet most imagine primitive tribes living in Edenic bliss. But you claim that these tribes are far from the noble savages portrayed by Rousseau. How homicidal were they?

Steven Pinker: Tribal groups show a lot of variation, but on average around 15 per cent of people in nonstate societies die from violence. This is the average I got from signs of violent trauma in skeletons from 21 prehistoric archaeological sites, and from eight vital statistics from eight hunter-gatherer tribes.

Hunter-horticulturalists and other tribal people have even higher rates of violent death – around 24.5 per cent. By comparison, the rate of deaths from all wars, genocides, and man-made famines in the world as a whole in the 20th century was just 3 per cent. Even the famously peaceful tribes, such as the !Kung and Semai, have homicide rates that rival those from the most violent American cities in their most violent periods.

Why is violence declining? What are the main civilising influences?

Steven Pinker: I identify four major forces: (1) The Leviathan – a government and justice system that deters people from exploiting their neighbours and frees them from cycles of vendetta; (2) Gentle commerce – an infrastructure of trade that makes it cheaper to buy things than to plunder them, and makes other people more valuable alive than dead; (3) Technologies of cosmopolitanism, such as reading, travel and cities, which encourage people to see the world through the eyes of others, and makes it harder to demonise them; (4) Technologies of reason, like literacy, science, history, and education, which make it harder for people to privilege their own tribe's interests over others', and reframe violence as a problem to be solved rather than a contest to be won.

Humans are very good at ignoring the big problems: climate change, overpopulation, dwindling resources. Won't it be a matter of decades before the next global conflagration hits us?

Steven Pinker: Maybe, but maybe not. For one thing, it's not a certainty that human will and ingenuity will fail to rise to the challenge. For another, the connection between war and resource shortages is tenuous. Most wars are not fought over shortages of resources such as food and water, but rather over conquest, revenge, and ideology. Nor do most shortages of resources lead to war.

For example, the Dust Bowl of the 1930s didn't lead to an American civil war (we did have a Civil War, but it was about something completely different); nor did the tsunamis of 2003 and 2011 lead to war in Indonesia or Japan. And several studies of recent armed conflicts have failed to find a correlation between drought or other forms of environmental degradation and war.

Climate change could produce a lot of misery and waste without necessarily leading to large-scale armed conflict, which depends more on ideology and bad governance than on resource scarcity.

In Better Angels, you describe Pepys witnessing a man being hung, drawn and quartered. Afterwards, clearly unperturbed, Samuel Pepys goes to the pub with his friends. Fast forward a few centuries and people are being diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after witnessing the 9/11 attacks on TV. Do you think a long peace might be detrimental to the robustness of humankind and hence might be our undoing?

Steven Pinker: That's the least of our worries. A century ago artists, critics and intellectuals gushed about the beauty and nobility of war, with its fostering of manliness, solidarity, courage, hardiness, and self-sacrifice. The First World War put an end to that. Better a little PTSD, I say, than the kind of indifference to the lives of men that resulted in the Battle of the Somme.

Nor has the Long Peace turned us into a civilisation of selfish wimps. However traumatic 9/11 may have been to some small number of people, it didn't stand in the way of heroic rescues, the rapid clearing of Ground Zero, and (for better or worse) a quick and successful invasion of Afghanistan.

'The Better Angels of Our Nature: The Decline of Violence in History and Its Causes' by Steven Pinker is published by Allen Lane (£30).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments