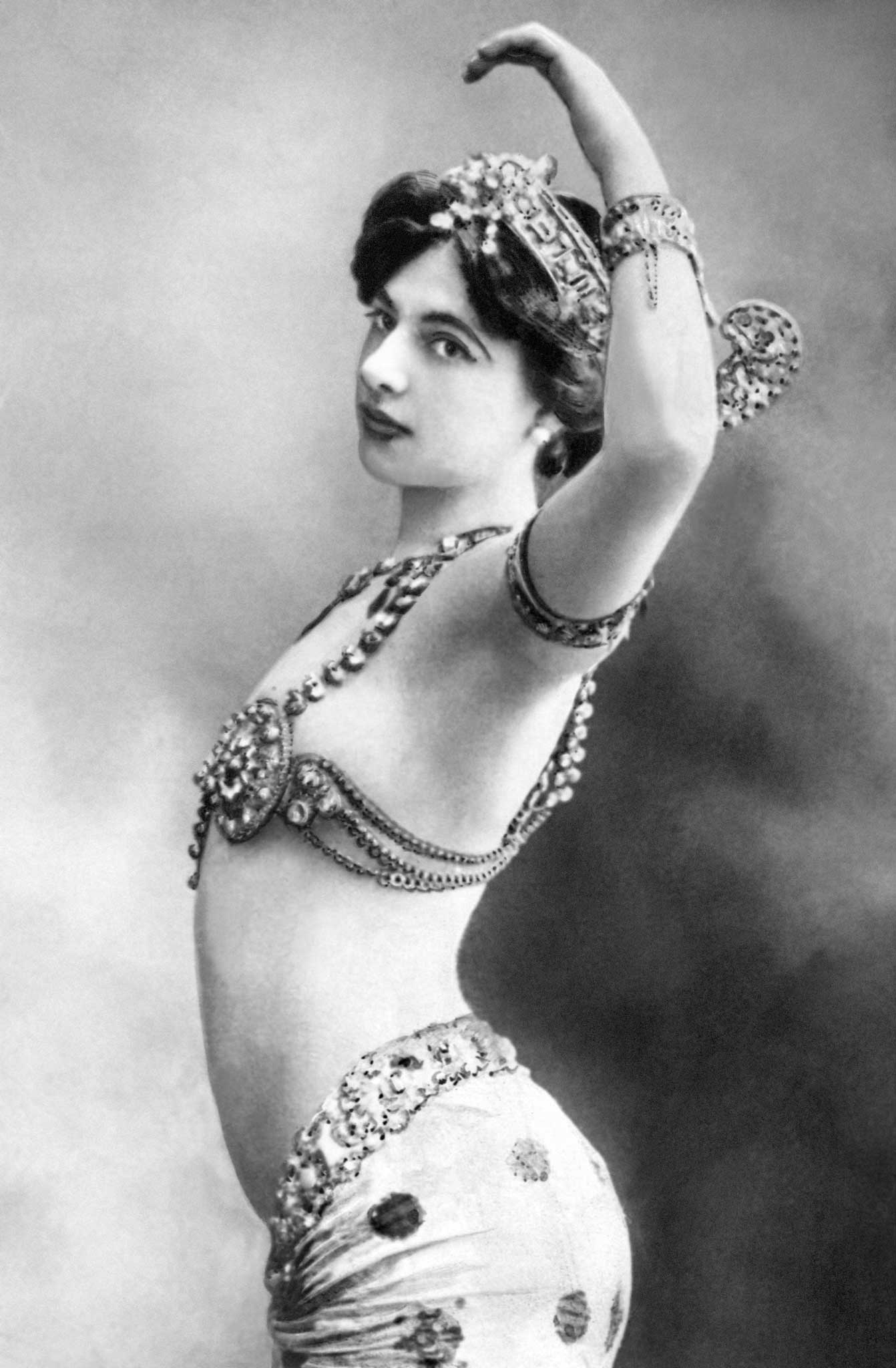

Spy fiction and non-fiction: From Mata Hari and Edward Snowden, with love

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Have we – the benighted members of the human race – ever trusted each other? Thomas Hardy talked about "nations striving strong to make red war yet redder", and such melancholy pronouncements seem even more on the nail in the 21st century when endless bloody battles divide nations, and foreign powers we thought had grown benign begin rattling their sabres again. Altogether, in fact, fertile ground for a new legion of books on espionage (both fiction and non-fiction), demonstrating that we have long maintained the ancient tradition of spying on each other.

Kristie Macrakis's Prisoners, Lovers & Spies (Yale, £18.99) is subtitled The Story of Invisible Ink from Herodotus to al-Qaeda, and this curious accoutrement of the spy's trade provides an immensely diverting overview of secret and hidden writing, from lovers making clandestine assignations to Mata Hari providing information for her paymasters and to details of terrorist operations hidden in pornography.

Fascinating though real espionage is, most of us prefer the invented variety, and splendid fiction in the genre abounds at present. Case in point: David Downing's Jack of Spies (Old Street, £8.99), which has already had aficionados reaching for new adjectives to praise the author. Part-time spook Jack McColl, working for the fledgling Secret Service in 1913, becomes involved with a seductive American journalist, Caitlin Handley – making a choice between Eros and Empire imperative.

Almost as accomplished is David Ignatius's The Director (Quercus, £18.99), in which hacked computer information has replaced Mata Hari-style boudoir indiscretions. Assange and Snowden are the government-destabilising spirits presiding over this complex thriller in which an American president attempts a massive spring clean of those supplying information to the Russians and to Islamic terrorists. An authoritative novel, it is perhaps undercut by the American author's tenuous grasp of English idioms.

If anyone deserves the sobriquet of the thinking person's Dan Brown, it's Tom Harper. Zodiac Station (Hodder, £16.99) handles with élan a multi-perspective story in which the eponymous Arctic station becomes a metaphor for multinational distrust. What is going on at the station? A US spy is convinced the station is riddled with Russian spies, positioning themselves for when the melting of the ice caps makes oil available and opens up new shipping routes. We can only hope Harper is not as prescient as he seems about the Arctic being a new frontier of the Cold War.

Back to non-fiction with Mike Rossiter's The Spy Who Changed the World (Headline, £20), a novelistic telling of the story of Klaus Fuchs. In 1945, Fuchs, a refugee scientist working for the British at Los Alamos, had been spying for the Russians for years. Rossiter addresses the key questions: how vital was Fuchs' spying to the Russians? When did his career as a Soviet agent really begin? It is a remarkable saga of clandestine meetings, deadly secrets, family entanglements and illicit passion, set against the years from the rise of Hitler to the start of the Cold War. Rossiter ends with MI5's failed attempts to trap Fuchs, and shows why, after giving away the secret of the atomic bomb, he finally made a carefully calculated confession.

If your tastes are for fact or fiction in espionage, your cup runneth over.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments