Sherlock Holmes and the case of copyright

A long-running legal battle in the United States could change the way Sherlock Holmes and other characters are portrayed in future books and films

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

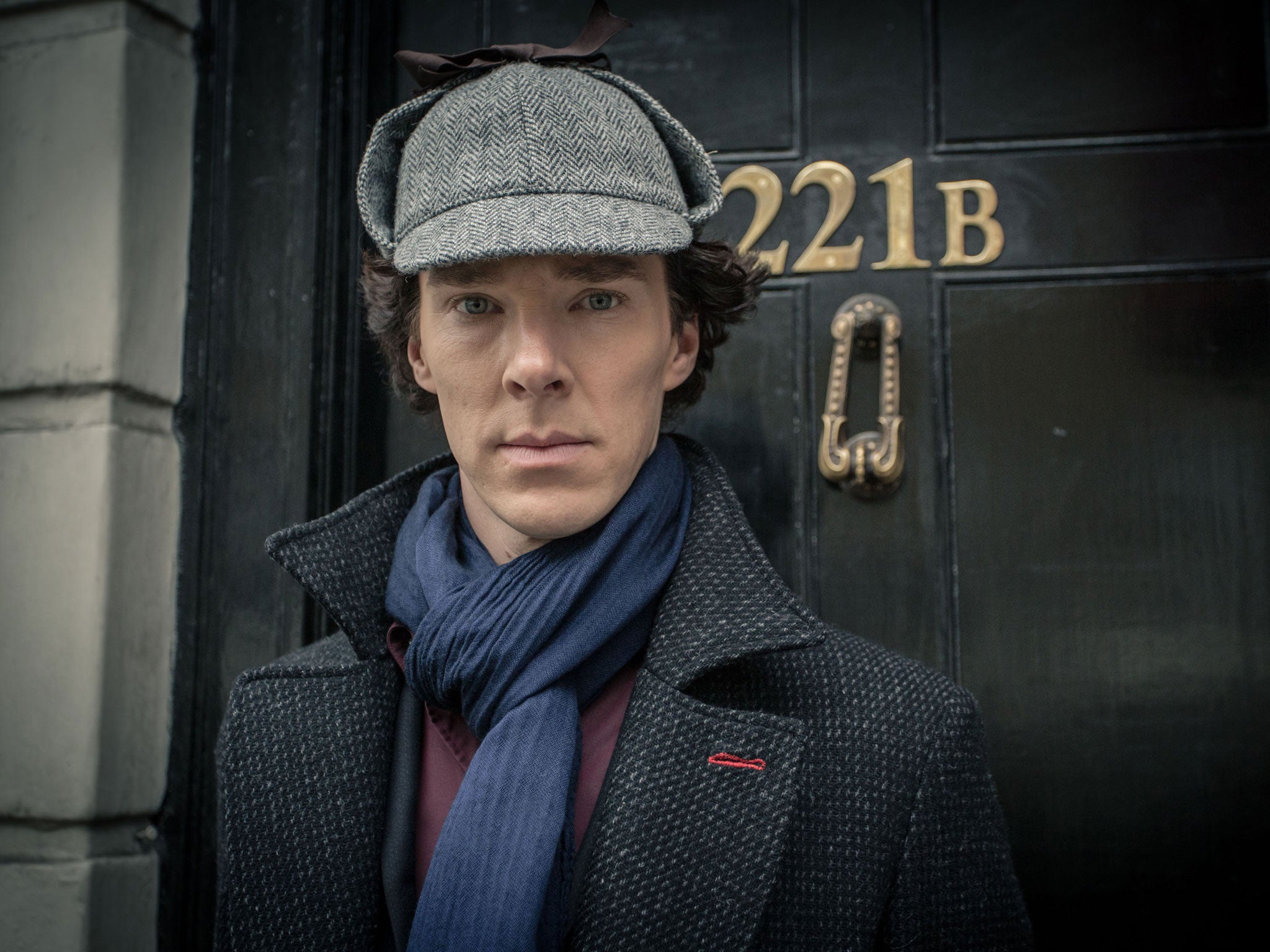

Your support makes all the difference.It is a case as puzzling as many of those to which Sherlock Holmes applied his extraordinary powers of deduction. As Benedict Cumberbatch divides audiences with his turn as the fictional detective, a legal battle in America may change the way Holmes and other characters are depicted on page and screen.

In the latest chapter in the saga, a federal US judge in Chicago ruled last month that an American writer and leading "Sherlockian" may publish work inspired by Arthur Conan Doyle's stories without fear of legal action by the Scottish author's estate, which is now expected to launch an appeal.

Watch: Sherlock 3 finale 'His Last Vow' trailer

Leslie Klinger says the estate had demanded $5,000 (£3,000) for the right to publish a book of new short stories featuring characters and elements from Conan Doyle's work. Klinger refused, arguing in court last February that he should be free to publish because the 50 original Conan Doyle stories now in the US public domain include all key characters and story elements.

Before we go on, an elementary lesson in copyright law: in the US, the term of copyright extends 70 years after the death of the author or – crucially – 95 years after publication. In short, that means 10 stories remain under copyright until 2022. In the UK, only the 70-year rule applies, so all Holmes stories have been out of copyright since 2000.

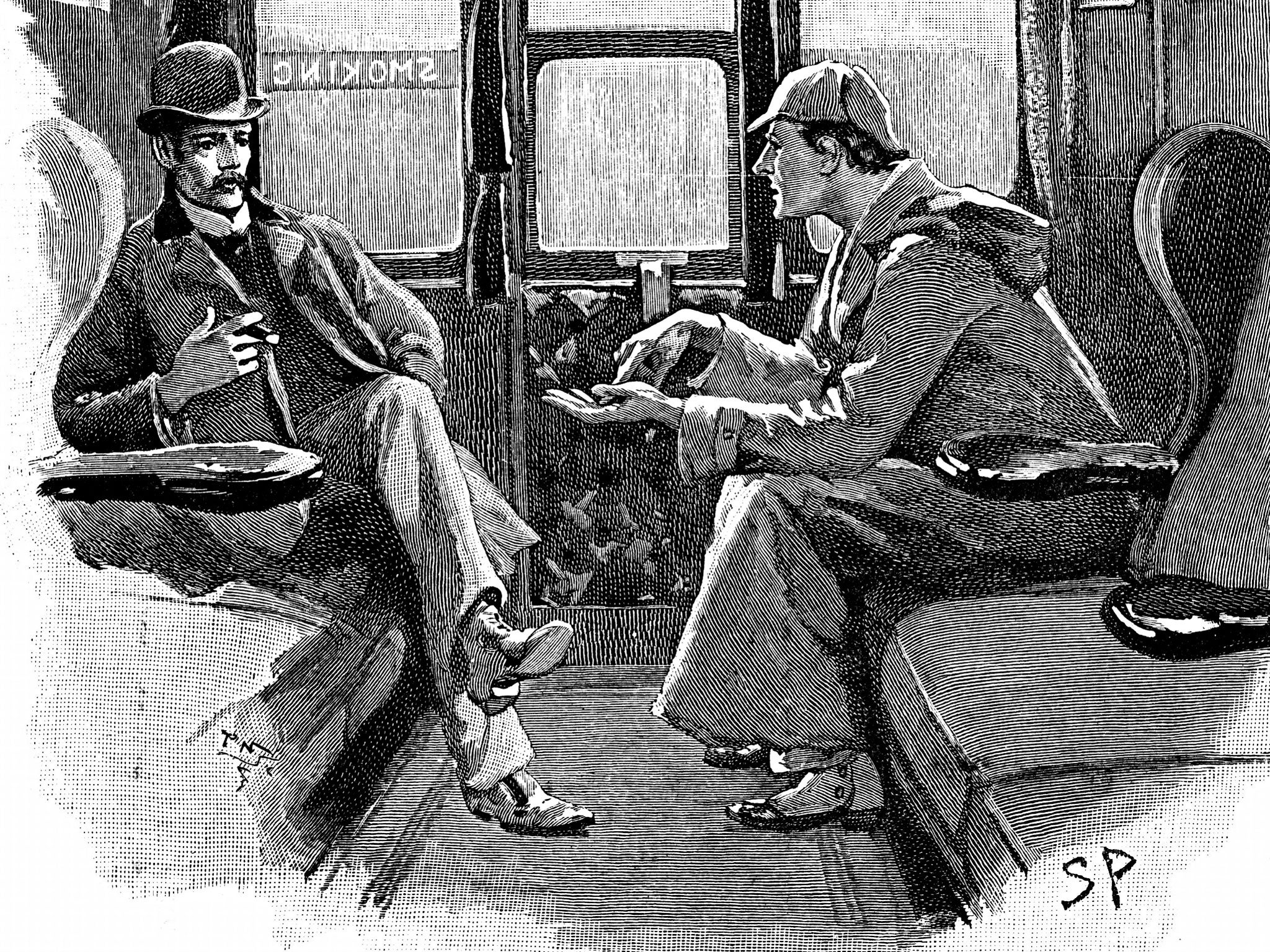

Conan Doyle's estate insisted that, until that expiration in 2022, Holmes remains a "single complex character" who cannot "be dismantled". Some developments could only be found in the stories still under copyright, it added, including the deepening of Holmes's friendship with Watson. The judge disagreed, ruling that anything published before 1923 was public property. While the estate considers its next move, the case highlights the complexities and competing interests involved in copyright law. Alistair McCleery, director of the Scottish Centre for the Book at Napier University, says the limitless economic value of characters such as Holmes distorts the intended purpose of copyright law.

"The norm used to be that copyright offered only limited protection so that the creator and a limited number of descendants could benefit economically. Now it's in so many people's interest to extend copyright as long as possible."

In 1995, the UK copyright term rose from 50 years to 70. It was extended in the US in 1998. In music, Cliff Richard led a successful campaign in 2011 to extend copyright, also from 50 to 70 years. McCleery says the risk of such extensions, whether by new legislation or clever legal argument, is that academic and creative work in the public interest may be inhibited. He cites the case of Alice Randall, who in 2002 settled with the estate of the Gone With the Wind author Margaret Mitchell. The estate had challenged Randall's publication of The Wind Done Gone, the same story told from the point of view of a slave on the US plantation depicted in the original. "This [book] was a very positive thing to do creatively, offering an entirely new perspective on the material," McCleery says in defence of Randall.

If Conan Doyle's estate won any appeal against the decision, it would raise new questions and potential challenges in the cases of similar characters. Perhaps most notably, the UK copyright protecting Ian Fleming's James Bond novels is due to expire in 2034. Like other estates with an eye on the future, however, his estate has cannily added another layer of protection by trademarking names including James Bond.

As further legal tussles loom, McCleery questions the role of judges in such disputes. "You're asking them to go beyond the judicial and make literary judgments," he says. "People have a right to make a living on what they compose but we've got to be aware of what we lose when work is kept out of the public domain."

His Last Vow airs on BBC1 at 8.30pm on Sunday 12 January

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments