Sex studies round-up: Physical love is still surprisingly contentious

From Sex By Numbers to Too Hot to Handle: A Global History of Sex Education

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

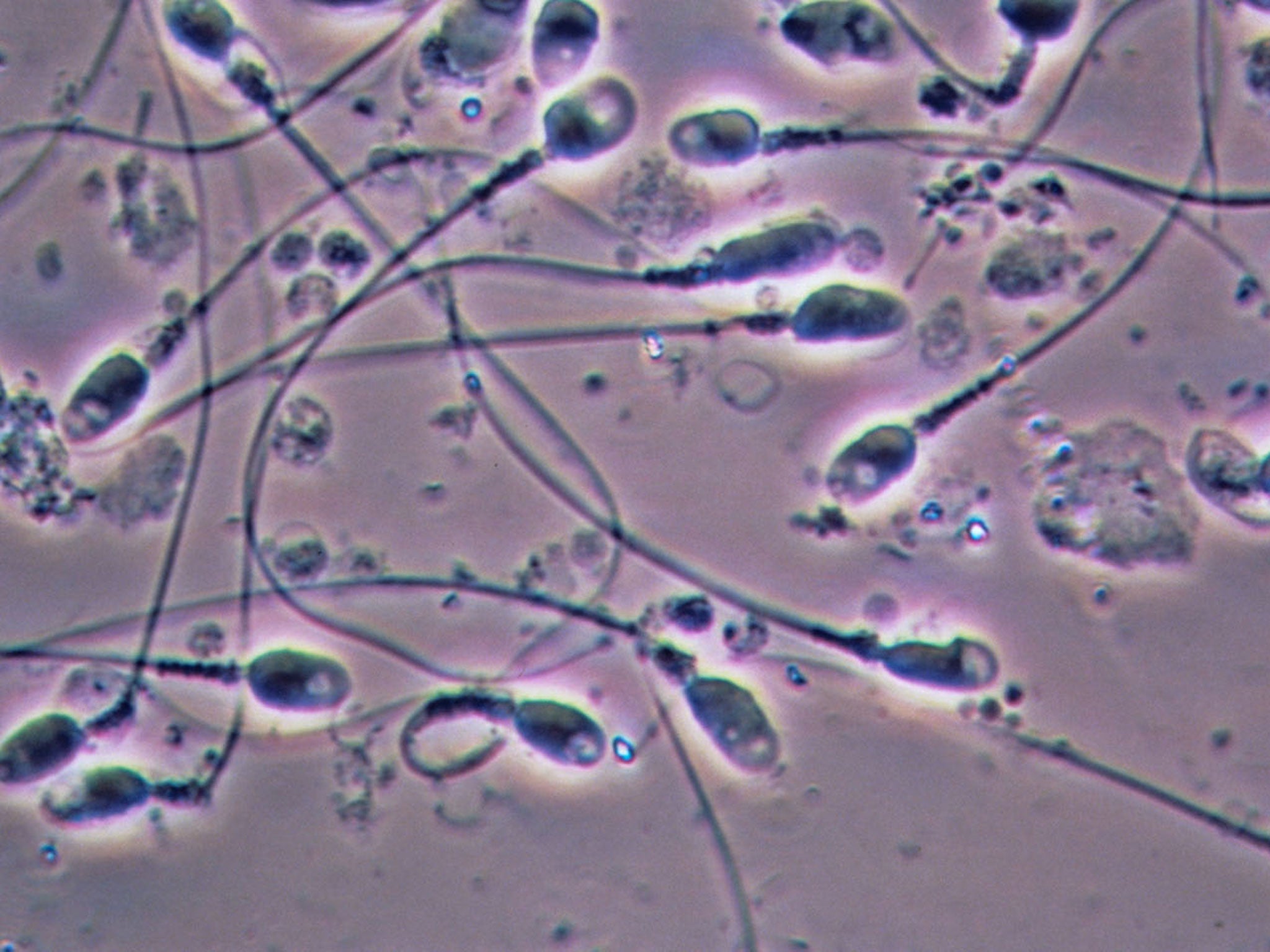

Your support makes all the difference.One of the more provocative figures from David Spiegelhalter's Sex By Numbers: What Statistics Can Tell Us About Sexual Behaviour (Wellcome Collection/Profile Books, £12.99) is the amount of semen being "produced" every minute across Britain: five litres (and that's based on the mean frequency of heterosexual intercourse alone). It certainly put a couple of friends of mine off their food as I announced it over breakfast on a recent hen weekend, but it gives you a good idea of what to expect from Spiegelhalter's study.

From how often we're doing it, what exactly we're doing and with whom (opposite sex partners, same-sex, or lone masturbation), the rate we're getting infected with STDs, to our cohabiting practices and everything sex-related in-between, Spiegelhalter, with the help of Natsal (the National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles), has got the numbers.

He debunks plenty of statistical myths along the way, most notably the classic "men think about sex every seven seconds"; and while acknowledging the significance of research such as Kinsey's then groundbreaking study of sexual behaviour in 1940s America, and the 1978 Hite Report on female sexuality, makes crystal clear their statistical shortcomings. Hite is given a 1* rating as even though her findings "portray valid, and vivid, experiences" her subjects were a "highly selected group" and her feminist agenda coursed boldly through their answers. Kinsey's stats, by comparison, fare slightly better with a 2* rating: "They might be used as very rough ballpark figures, but the details are unreliable".

Thus Spiegelhalter – a professor of risk at Cambridge University, not a sexologist – manages to teach his readers as much about stats as he does about sex (no mean feat!), explaining the logistical problems of reconciling this most secretly and privately guarded aspect of our lives with the world of precise facts and figures. Rendering sex in these terms is no straightforward task: for example, women told they were hooked up to a lie detector admitted to having had more sexual partners than those without the fake gadgetry attached.

It's fascinating stuff, but it goes without saying that this kind of study has its limits, not least when it comes to the more complex areas of desire and intimacy. Spiegelhalter briefly introduces us to Dr Clelia Duel Mosher, a little-known American contributor to the history of the sex survey, but one who asked her female subjects all about their attitudes, desire, and arousal – pioneering stuff considering it was the 1890s. She wasn't offering these women any advice, but she was certainly paving the way for the sex educators of today like Emily Nagoski whose self-help/sex education book, Come As You Are: The Surprising New Science That Will Transform Your Sex Life (Scribe, £12.99), screams female empowerment loud and proud; first instruction in chapter one is to get a mirror and look at your clitoris.

Nagoski claims to tell the true story behind female sexuality, though I can't say it made for particularly revelatory reading. Some of the terms might be new – "arousal nonconcordance", when the behaviour of your genitals suggests you're ready for sex but you don't feel turned on; or "responsive desire", wanting sex "only after sexy things are happening" – but the overall message is familiar: female desire and arousal is much more complex than we've traditionally been led to imagine; and we are all different, but all perfectly normal too.

If, however, you're more interested in the "education" than the "help" element, Jonathan Zimmerman's Too Hot to Handle: A Global History of Sex Education (Princeton University Press, £19.95) offers a dense and detailed account of a still surprisingly contentious subject despite our increasingly liberal attitudes.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments