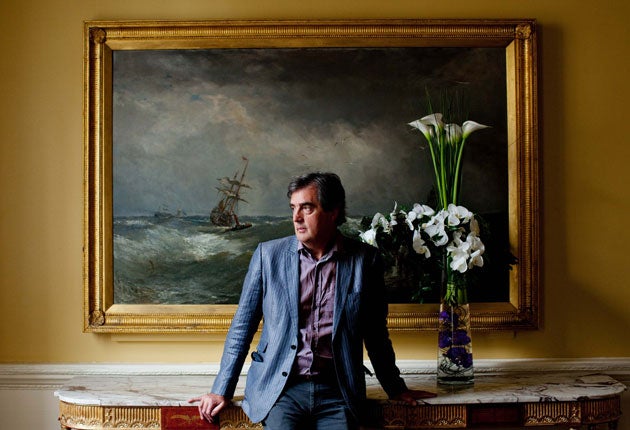

Sebastian Barry: Troubles in the family

The Booker-longlisted author Sebastian Barry tells Leyla Sanai how his own ancestors' bloody history inspires his novels about Ireland's violent past

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Hanging in the Dublin National Gallery is Sean Keating's 1922 painting An Allegory, showing a republican and a loyalist digging the same grave.

It sums up the internecine conflict of early 20th-century Irish history that Sebastian Barry's fiction explores. Much of his work is set around the 1916 Easter Rising and the subsequent signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. Rebels fought for independence and waged war on those they perceived as traitors in loyalist organisations like the police or army.

Barry's latest novel, On Canaan's Side, which was longlisted last week for the Man Booker prize, deals – as did his The Whereabouts of Eneas McNulty in 1998 – with individuals forced to flee. The exiled are a couple, Lilly and Tadg. Many of the book's characters have appeared in Barry's other work – Lilly's sister Annie in Annie Dunne; her brother Willie in the 2005 Booker shortlisted A Long, Long Way, and their father Thomas, based on Barry's maternal great-grandfather, a chief superintendant of the Dublin Metropolitan Police, in The Steward of Christendom.

In person, Barry is smart, affable, funny and eloquent, his speech punctuated by those evocative similes and metaphors that stop you in your tracks with their striking imagery and mellifluous poetry. I ask him about his characters, and how many of their stories are true.

"The three books are about great-aunts," he says, referring to Annie Dunne, On Canaan's Side and The Secret Scripture, the last of which was based on the sectioned wife of a great-uncle. "And two of them are sisters. So there's a DNA that binds them. Annie was the only one I knew; my beloved great-aunt who had a hunchback and didn't marry – it was ludicrous: it was from polio, but it was thought that she'd hand it on to her children.

"I invented Lilly's life but the events were based on truth. I met a cousin who told me about a great uncle of ours, Jack, who had come home from the First World War and joined the [Black and] Tans. There was an IRA ambush and the IRA suspected Jack had known about it and informed his father, the policeman. They put a death sentence on Jack. My great-grandfather was from the same area, so the IRA warned him that a death sentence had been put on Jack and Jack's friend. My great-grandfather managed to get his son out of Ireland, but Lilly was dating Jack's friend, so she had to go too. And in Chicago, my great uncle was shot. This was an immense event in my family, but no one ever mentioned it. The whole thing was covered over with a terrified silence. My great-grandfather probably died of a broken heart."

Barry's family history is the inspiration behind many of his novels, thanks to the stories that were passed on to him by his mother. But this caused a rift between Barry and his grandfather which never healed: later in our interview, he wipes away a tear when he describes his grandfather's anger at seeing such intimate family memories used in fiction. They never spoke again, despite the older man's attempts to make amends.

Nonetheless, this use of the real Lilly's life is important because it shows that extraordinary events – death threats and exile – occurred in Ireland at that time. Hopefully this will mean that On Canaan's Side is not subjected to the same criticisms received by The Secret Scripture, which the 2008 Man Booker judges said did not win because of the "implausibility" of its ending. Barry says that he has been careful, with this latest novel, to make the events not only plausible but real. So how does he feel about his Booker longlisting?

"It's lovely really, like a very well-chosen gift ... I was walking in the Wicklow mountains when my editor at Faber rang. It was a moment of pure happiness, plain and simple. If it's the circus, this is the one the writer wants to run away with."

On Canaan's Side is written in the first person, from Lilly's point of view. Is it difficult to inhabit the mind of an elderly woman, as he also did in The Secret Scripture? "The first thing I'm after is the broken music of the book," he replies. "I have a trust in waiting for that voice, that birdsong of the character. So you're in the dark with it – you're listening for that faint tune, like a broken-hearted bluegrass song in the distance, and the hope and prayer in the privacy of my own mind is that this is the authentic tune of the character. Woe betide you if you force it, and anyway, there's no point, because it will just become a wasteland before you, and every tree and flower will disappear off the ground."

I ask Barry about the mixture of tragedy and joy in his work. "On the one hand you have your children – and I look on my children and wife as a branch of my true work in this life – and on the other, you're dealing with this landscape of tragedy, like people's illnesses.

"That's what's saved me, in that tuppeny-ha'penny journey that no one gives you a ticket for, and indeed, with destinations you never planned to go to. What has kept me sane is things like my son Toby playing the piano at the age of six and composing at the age of seven. To be witness to that is obviously a joy. As Roseanne [in The Secret Scripture] would say: 'itemise happiness', because there's little of it. When you have it, record it, harvest it, store it up like a squirrel against the winter."

I ask how he made the grief in the novel so credible. Barry relates the story of his dear late friend Margaret, to whom he dedicated The Secret Scripture. "When she was very ill, her grandson, Erskine, who had been in the Irish Guards in Afghanistan, came home. But one day he hung himself. And Margaret said 'Why didn't he take me? I was ready to go.'" That was the most brave, the most terrifying thing I'd ever heard a human say.

"Although The Secret Scripture was given to her, to try and honour, in a small way, my friendship with and gratitude to her, On Canaan's Side was in a way her gift to me. Because having told me that, how could I not know the sorrow of Lilly? And she was saying it to someone with sons." He wipes an eye. "We had had no piano for a while, so Toby would go to her house to play the piano, and on the piano she had a photo of Erskine. So I'm looking at Toby, then Erskine – there was huge identification there."

Imbued with sorrow, joy, tenderness and also moments of great humour, On Canaan's Side is a luminously beautiful story that well deserves its place on the Booker longlist, and beyond.

On Canaan's Side, By Sebastian Barry (Faber £16.99)

"That hand in mine, that woundable hand, the woundable hand of every child, us moving through the gentle public gardens of Washington ... A woman approaching fifty, and a little neat boy with close-cut hair.

Our smiles mostly for each other, and every stranger a possible demon or bear, till they proved otherwise."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments